Like many of us who are mindful of our plastic consumption, Beth Gardiner would take her own bags to the supermarket and be annoyed whenever she forgot to do so. Out without her refillable bottle, she would avoid buying bottled water. “Here I am, in my own little life, worrying about that and trying to use less plastic,” she says. Then she read an article in this newspaper, just over eight years ago, and discovered that fossil fuel companies had ploughed more than $180bn (£130bn) into plastic plants in the US since 2010. “It was a kick in the teeth,” says Gardiner. “You’re telling me that while I am beating myself up because I forgot to bring my water bottle, all these huge oil companies are pouring billions …” She looks appalled. “It was just such a shock.”

Two months before that piece was published, a photograph of a seahorse clinging to a plastic cotton bud had gone viral; two years before that England followed Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland and introduced a charge for carrier bags. “I was one of so many people who were trying to use less plastic – and it just felt like such a moment of revelation: these companies are, on the contrary, increasing production and wanting to push [plastic use] up and up.” Then, says Gardiner, as she started researching her book Plastic Inc: Big Oil, Big Money and the Plan to Trash our Future, “it only becomes more shocking.”

Her research took her to Reserve, Louisiana, in the Lower Mississippi River, where she met Robert Taylor, an activist in his 80s who has spent much of his life living by an enormous plastics plant. “He is surrounded by illness, by all kinds of cancers. He only found out in 2016, as a result of federal action, that the levels of toxic gases had gone through the roof in his area, an overwhelmingly Black neighbourhood. He told me about all the illness in his family – affecting his wife and his daughter, his neighbours and his cousins. It was haunting. When we talk about plastic, we tend to think about the ways we experience it in our own lives, and we’re not as aware of the production and the impact it has on the people who live beside it.”

In Indonesia, Gardiner visited a hill of dumped plastic. The material was “as far as the eye could see. I walked around on top of it, and picked up packaging from brands that I know, both in the UK and the US, and in European languages.” It had been dumped by a paper factory that imports waste paper, in bundles that are contaminated with plastic – possibly the plastic we think we are recycling. “It was very sobering to be on the other side of the world and see these brands.”

Gardiner was not naive – an environmental journalist from the US, now based in London, she had written a book, Choked, on air pollution. She was well aware of the tactics and impact of the oil industry. But she was still shocked. “I think what stood out most is the deliberateness and intentionality over the years of pushing plastic into our lives,” she says. “If you look back to the 50s and 60s, when this model of disposability was being invented, there are speeches given at plastics industry conferences, saying: ‘We can make so much more money by selling a bottle that will be thrown out than selling a bottle that gets reused 20 or 40 times.’ I guess what shocked me the most is the deliberate way that they built this world that we live in. They understood the impact, the consequences, and they saw the profit that it offered and that overrode everything else.”

In the past 20 years, Gardiner writes, plastic production has doubled, and it will double again, perhaps triple, in the near future. Petrochemicals for plastic are, she says, “expected to be the largest single driver of oil demand in the decades to come. Obviously these oil companies can see what’s coming – they understand that that shift away from fossil fuels is a threat to their business model that has been so profitable for them.” Plastic, she says, “is a way for them to keep drilling and to keep making money. Putting their expertise and muscle into solar or wind power was not the way they wanted to go. It’s not as profitable as selling oil and gas, so they’re all in on the current model, and plastic is a way to perpetuate it. Which is why it is, I guess, even more catastrophic. Because if it’s enabling the industry to keep drilling, to keep selling oil and gas, that is a huge threat to the climate.”

The extraction and transport of fossil fuels, and manufacturing and disposal of plastics, all create carbon emissions. According to the UN, in 2019, plastics generated 1.8bn tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions – 3.4% of total global emissions.

Meanwhile plastic has contaminated the planet. Microplastics – created when plastic degrades – have been found in the deepest ocean and on top of Mount Everest. They’re in food, water and the air we breathe. Studies have shown the presence of microplastics in humans, and although the reliability of tests and the levels found has recently been questioned, the presence of microplastics isn’t in doubt.

“The research on microplastics is very new, and this is science doing what science needs to do,” says Gardiner. “We don’t know everything we need to know about microplastics, but it’s important to understand that this is only one piece of the health harms. There’s a much longer history of research that is much clearer about the chemicals in plastic that leach into our food, drink, our environment, our bodies.” This includes chemicals that disrupt the endocrine and cardiovascular systems, and are linked to cancer. “We have to wait and see where the research shakes out on microplastics, but I don’t think that should distract us from the bigger picture. Microplastics is just one piece of the health harm that plastics are doing.”

Plastic is derived from fossil fuels, but the end products – the number of crisp packets I throw away each week, or the new trainers I want – are so far removed from the source that this fact barely registers. It was the same for Gardiner, she admits with a laugh, and she is an environmental journalist. “That inscrutability has been very beneficial to the industry.” Would it help if plastic was rebranded in the popular imagination as a fossil fuel product? “I think so. I guess what I’m trying to do with this book is help people understand the origins of this plastic mess that we’re in, and part of that is understanding who is driving it, and that it’s not us as individuals.”

Ironically, plastics were developed in the mid-19th century as a response to environmental concerns, such as elephants being hunted for ivory. Early plastics, such as parkesine and celluloid, were derived from plant-based cellulose, and in the first decades of the 20th century, more plastics, or polymers, followed, the results of experiments with chemicals derived from fossil-fuel processing, and including polystyrene, nylon and PVC. The world’s most common plastic, polyethylene, was created by British chemists in 1933.

“Plastic is supply-driven rather than demand-pulled,” says Gardiner. “Plastic has always had this unique ability to reverse the relationship between supply and demand.” The materials being used were by-products of oil and gas processing. Companies were looking for uses for them – and realised they could make a profit. They wooed the public with promises of convenience and disposability. Plastic, says Gardiner, is “the foundational material of modern consumerism”. It is undoubtedly useful, and because so much was being produced, it is cheap and widely available. Products started appearing, from pens and cigarette lighters to nappies and cups, that used to be reusable. And disposability meant more profit.

It wasn’t that the public ignored the harms. “There have always been these moments of potential crisis for the industry,” says Gardiner. “There was a panic over landfill space – that was a big issue in the US in the 70s and 80s. More recently, the David Attenborough [Blue Planet] documentaries and the videos of ocean plastic. These moments of public concern about the impact of waste have bubbled up regularly over the last 50-some years. They are a threat to the industry, and they have a lot of tactics for defusing them.”

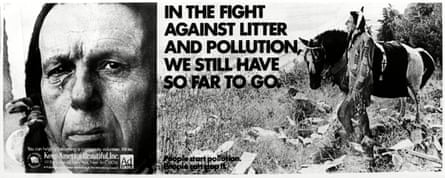

One of the most effective, she says, is to shift the focus on to individuals. “[People in the plastics industry] are very happy for us to look at ourselves and at each other, and not look at them,” says Gardiner. Plastic was framed not as an overproduction problem, but as a litter problem. In the US in the late 50s, food, drink, cigarette and packaging companies formed the organisation Keep America Beautiful, spending huge amounts on promoting themselves and the message to put rubbish in the correct places. “No one really knew the industry was hiding behind this anodyne name. Keep America Beautiful was widely understood as a civic-minded organisation of some sort.”

It was a similar story with recycling. “Recycling has been a big part of their arsenal. I think the thing that was so shocking was to read these documents and conference transcripts, going back to the 70s, to see that they understood it is really hard to make plastic recycling work.” They also understood that an attempt at recycling would make consumers less guilty about the waste they were producing – a feeling I know well, every time I smugly dump a bag of soft plastics in a supermarket recycling bin. “They pushed so many myths and lies about recycling.”

Recycling has value for materials such as cardboard, glass and cans – “even so, we should be using way less” – and for some plastics, such as PET drinks bottles. But for most plastic, it is inefficient and expensive, and releases harmful toxins. Meanwhile, the plastic degrades each time it’s recycled, simply delaying its eventual final resting place in landfill (or incineration). “They’ve worked very hard to muddy our understanding of what is possible and what recycling can offer,” says Gardiner. “Because the reality is: very little. It’s taking advantage of our desire to be more environmentally sustainable.”

Meanwhile, Gardiner details how the fossil fuel and plastics industry – in many cases one and the same – has lobbied to prevent legislation and scupper bills that would regulate it. Last year, lobbyists flooded UN-hosted talks to derail the global plastics treaty to tackle plastic pollution. A post-Brexit Britain has separated itself from EU regulations on plastic. “The EU has been far from perfect, but they are the most aggressive regulator, both of these chemicals coming from plastics and of single use plastics,” says Gardiner. The US, she says, is “a whole other story”.

There is, she says, “zero prospect for any kind of effective regulation of plastics under the Trump administration. Every environmental regulation is going backwards.” In the US, there has been local and state level action, such as in California, which has just extended its ban on plastic bags to include the thicker “bag for life” types, and laws to make plastic producers – rather than the taxpaying public – responsible for the life cycle of their products.

There have also been the campaigns by communities and individuals, such as the 30-year fight by Diane Wilson, who took on the plastics giant Formosa which was contaminating the Texas coast with plastic pellets. In Europe, there’s the current battle against the building of what will be the continent’s biggest plastics plant, in Antwerp. The way the industry retaliates against even the smallest actions shows how worried it is about the potential for knock-on impact, says Gardiner (she writes about the pressure applied to a small town in Arizona which tried to enact a bag ban). “That tells you that those actions matter. It’s hard to see very much optimism now on any environmental issue in the US, but there’s possibility for it.”

And the west is starting to have to deal with its own mess. In 2018, China banned the import of waste, including plastic. “There is this global cat and mouse game where the waste just ends up going somewhere else and it’s a very opaque industry,” says Gardiner. But other countries, such as Indonesia, are also banning the import of our plastic. “There are more recycling plants and incinerators being built in the UK and around Europe,” says Gardiner. “In the UK, a lot of it ends up getting burned. I see these trucks go by because there’s an incinerator nearby, they have this branding on the side, ‘waste to energy’ or something, and you’re supposed to think, ‘Great!’ But they’re burning it.” This creates electricity, but also huge carbon emissions and toxic gases (the plants are usually built in deprived areas).

Gardiner still carries her reusable shopping bags, and water bottle. “They do matter, but I’ve shifted my focus. What I’m trying to do with this book is to help people look away from the personal and more towards the political because that is where the difference is to be made.”

The thing is, a world before plastic is within living memory, and returning to aspects of it is hardly like going back to the stone age. “You only have to look back to our grandparents’ time, or even our parents’ time. We can use much less plastic without using no plastic, and that is unpicking another industry talking point – they will talk up the environmental benefits, that it’s part of solar panels, and it helps to make cars lighter so they’re more fuel-efficient, and do you want to live in a world with no hygienic syringes? It’s important to challenge that framing, because some of those things are true and we can keep the uses that are essential, but it doesn’t mean that we have to accept this tide of junk. We don’t have to look too far back into our collective memory to see ways that we could live that are less wasteful. It’s not impossible, because it existed.”

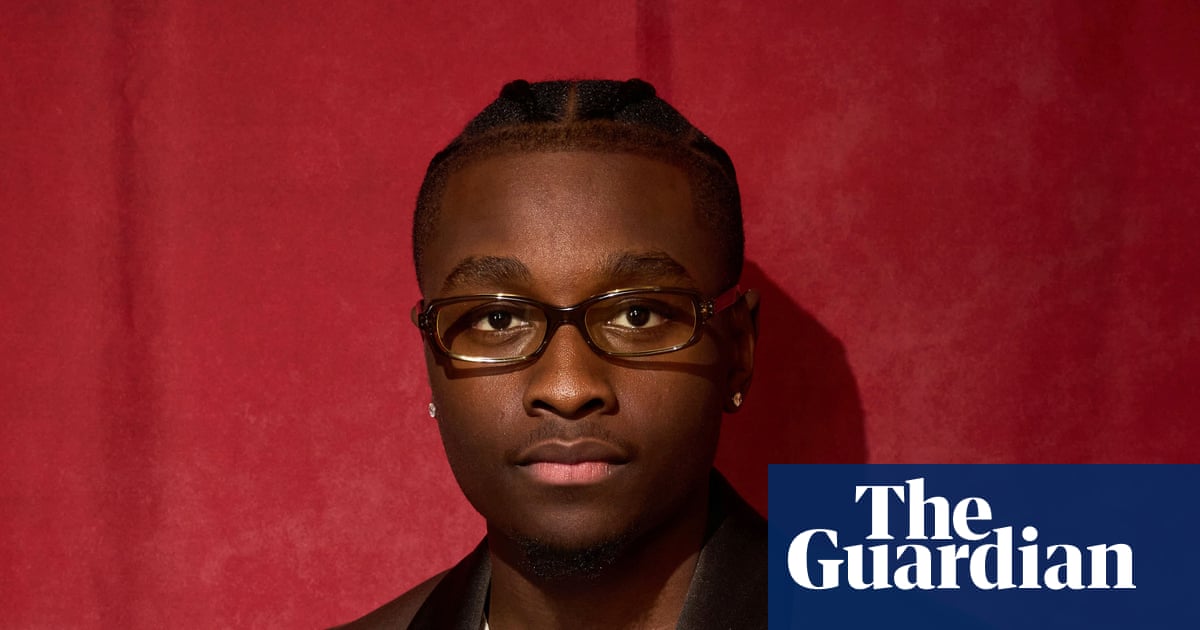

Plastic Inc: Big Oil, Big Money and the Plan to Trash Our Future by Beth Gardiner is published by Monoray on 26 February (£22). To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2