This is Muslim *a non-exhaustive list of the artists, politicos, and entertainers driving the city's new era

Against the backdrop of Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral rise is a dynamic scene of Muslim creatives and intellectuals who are helping usher in a new era for New York City. Their prominence represents a rebuke of the ugly Islamophobia that defined the period following 9/11, and is in many ways an outcrop of the mass movement for Palestinian rights forged over the last two years. We ask 18 Muslim New Yorkers to discuss their work and what this moment means.

How Muslim New Yorkers are changing the city’s cultural landscape

The writers

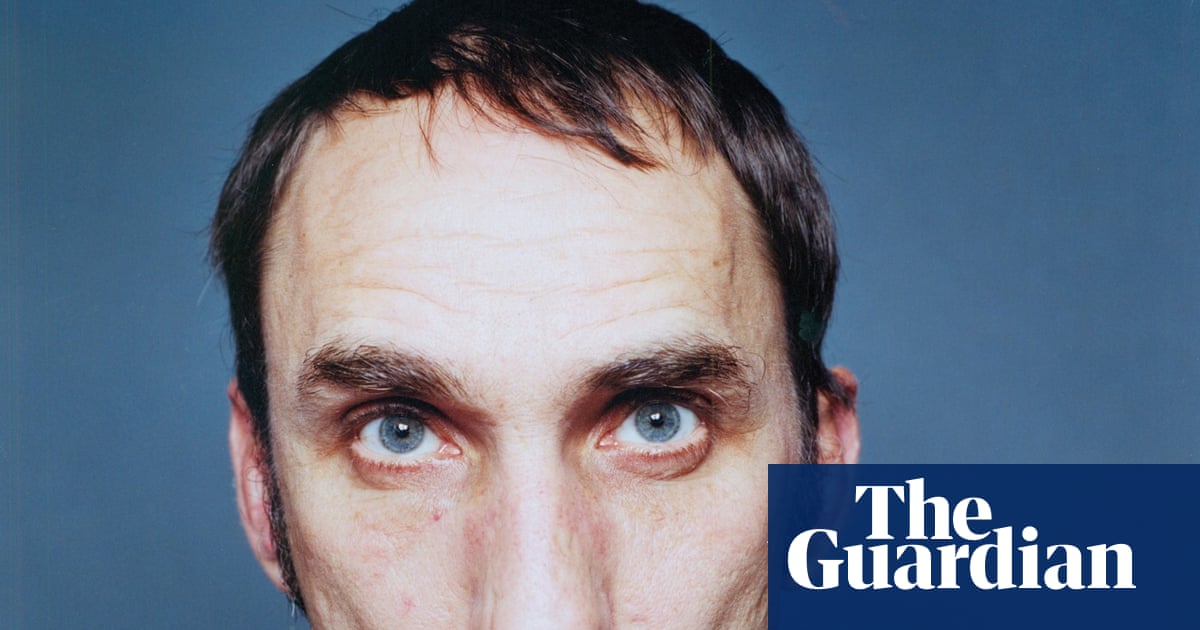

Hala Alyan & Mohammed Mhawish

A celebrated Palestinian-American writer and poet, Hala Alyan explores themes of exile and belonging in her work. Based in Brooklyn, the 39-year-old hosts a popular live performance series called Kan Yama Kan (One Upon a Time in Arabic), which fundraises for causes from Gaza to Sudan to reproductive justice. Her recent memoir, I’ll Tell You When I’m Home, excavates her family’s history of displacement throughout the Middle East and the US, alongside her own struggles with infertility. A psychology professor at New York University, Alyan believes stories like hers resonate because audiences are hungry for connection. “People are quite starving for emotional touch, psychological touch, narrative touch, to be let into other people’s worlds,” she says. “That’s what art is – a conduit for curiosity, right?”

Mohammed R Mhawish didn’t set out to write on war. He dreamed of teaching Shakespeare and writing fiction. His creative writing teacher at university, Refaat Alareer, encouraged it. But growing up in Gaza, war reporting carried more urgency. After October 7, Mhawish lost multiple journalist friends to Israeli attacks and was nearly killed when an airstrike hit his home. That strike prompted his departure from Gaza – and ultimate move to the US – with his family. At 25, Mhawish is a contributor to The New Yorker, among other publications. He feels lucky to be in New York – but also a new level of responsibility. “I get to enjoy this really incredible, genuine fabric of community,” he says. “All of a sudden you’re feeling a different load of recognition, but it’s also heavier in a way that makes your work all the more urgent.”

The strategists

Zara Rahim & Waleed Shahid

It wasn’t long into Zara Rahim’s career in communications that she became known as a rising star. A first-generation Bangladeshi American from Florida, Rahim had worked for Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaigns before turning 30. But her role as a senior adviser to Mamdani is Rahim’s most stunning accomplishment. She helped shape his keep-it-simple messaging and spearheaded a strategy that favored authenticity – neighborhood restaurants, Knicks games, rock concerts – over a traditional media strategy. Now 35, Rahim says she joined the campaign because she was “disappointed by the Democratic party” over its stance on Gaza and struck by Mamdani – a “young, Muslim, smart, charismatic principled young man who gets it”. Rahim says his victory really hit home when she toured city hall after Mamdani was sworn in. Portraits of past mayors, largely white men, dotted the walls. “That moment was like, ‘Oh my God. We did it.’”

Waleed Shahid has played a leading role in the progressive wing of the Democratic party – he helped recruit a bartender from the Bronx named Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to run for Congress, was the communications director for Justice Democrats, and co-founded the Uncommitted Movement to press Democratic candidates to take a stand on Gaza. For Shahid, Mamdani’s victory was clear evidence that voters care deeply about issues that the party historically dismissed. “His election was a watershed moment in Palestine politics in this country,” Shahid says. “You cannot tell the story of his campaign without telling the story of Palestine.” Now, Shahid serves in Mamdani’s administration as deputy communications director of economic justice.

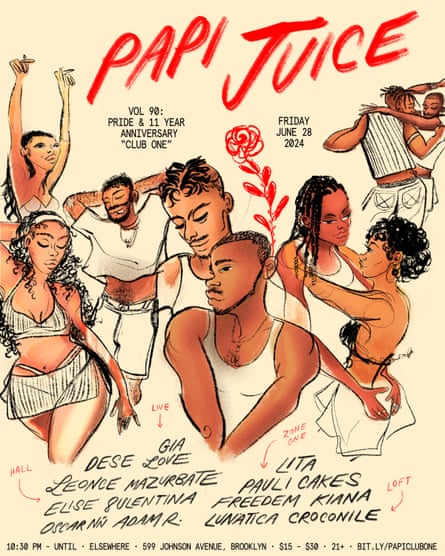

The connectors

Mohammed Iman Fayaz & Gehad Hadidi

Known for its lively parties, the Brooklyn art collective Papi Juice made headlines when Mamdani stopped in on the weekend before his election. Mohammed Iman Fayaz, a 35-year old illustrator, is one of the brains behind the collective, which he started in 2013 with two friends to provide safe space for queer people of color. Growing up, Fayaz says he struggled to be both queer and Muslim at the same time. That changed in 2024 when he went to Mecca on pilgrimage with his mom. “Once I got there, I felt like I saw that wall drop,” he says. “I realized we’re all just kind of doing our best in front of God.”

As a kid, Gehad Hadidi says he would draw restaurants with little menus for him and his friends. Today, the 42-year-old runs Huda, a restaurant in East Williamsburg that has become a convergence point for the city’s Muslim creatives and intellectuals. The spot has a room dedicated to cultural and community events (Rama Duwaji, New York City’s first lady, has hosted private ceramic classes there; her art adorns the walls.) Hadidi named Huda after a Muslim community center he frequented growing up in Michigan. “It’s a place where [people] can go and bring their kids to do Arabic story time, or watch an interesting film,” he says. “We’re part of the fabric of the neighborhood in a more meaningful way than just where you occasionally grab dinner.”

The advocates

Mahmoud Khalil, Ramzi Kassem & Aber Kawas

Mahmoud Khalil is still here, despite the Trump administration’s best efforts. The Palestinian activist and former Columbia University student leader, now 31 years old, was detained last year in an unprecedented crackdown against pro-Palestinian speech. He has since been released and continues to fight his deportation. The week of the Guardian’s photoshoot, an appeals court delivered a setback in his case when it opened the door to his re-arrest. It rattled him, but “this city, in small, very persistent ways, has also told me that I’m welcome”, he says. Khalil knows that he’d like to raise his baby boy here, so he says he’s resisting despair. “We don’t have any other option other than being hopeful. They want people to feel hopeless,” he says. “We have to fight.”

Few people have been closer to the center of contemporary Muslim New York than Ramzi Kassem. Before he was tapped to serve as Mamdani’s chief counsel, Kassem was a prominent civil rights attorney defending New Yorkers from some of the worst post-9/11 abuses from his perch at Clear, a law clinic. In 2013, he was part of a team that sued the NYPD for its sweeping surveillance of Muslims, leading to major reforms guarding against discrimination. “We’ve been dealing with Muslims having their devices taken from them at airports,” Kassem says. “Now that’s being experienced by a broader set of people. I think at this moment the lived experience of Muslim communities in the United States can lead the way.”

Aber Kawas never thought politics were for her – until now. The 33-year-old Palestinian-American community organizer is running for state assembly in one of Queens’ most diverse districts. A member of the Democratic Socialists of America, which propelled Mamdani’s mayoral bid, Kawas sees him as an example of how to be a politician “in a values-aligned way”. Raised in Brooklyn, Kawassaw her father, who was undocumented, deported when she was a child. Later she would learn that some of the businesses, mosques and student groups that made up the fabric of her life fell under the NYPD’s warrantless surveillance program. Now, she’s taking up Mamdani’s focus on dignity for the working-class. “I think the most beautiful part of Zohran’s campaign is when he would go to Kebab [King] and serve the taxi drivers biryani,” she says. “That’s what I’m hoping to do – center those people.”

The artists

Sarah Elawad, Dean Majd & Laylah Amatullah Barrayn

The low-fi memes that circulate on Whatsapp throughout the Middle East, Africa and their diasporas serve as core inspiration for Sarah Elawad, a British-Sudanese artist based in Brooklyn. Elawad, 29, is known for her maximalist and ultra-neon designs and created some of Mamdani’s most fun campaign visuals. In 2025, New York’s Africa Center commissioned her to create a massive installation currently installed over their Fifth Avenue windows, called When the War is Over. Recently, Elawad, who has taught design at Pratt Institute, says she toyed with leaving New York before deciding against it. “The community that I have in New York and the kind of rush I feel around creating doesn’t exist anywhere else,” she says. “This is where I need to be right now.”

Photographer Dean Majd, 35, says growing up as a Palestinian New Yorker informs where and how he chooses to direct his lens. Israel’s occupation, and Islamophobia and racism in the US, he says, has fostered an empathy he brings to his work. “Even as a Palestinian, I’m also an American from New York. That’s such a specific experience.” These days, the self-taught artist is having quite the run – he has photographed Mamdani for Vogue magazine and he captured the first portrait, for Dazed Magazine, of Mahmoud Khalil and his family after Khalil’s release from an immigration detention facility. Next up: his first solo show at the Baxter Street Gallery at The Camera Club of New York.

Laylah Amatullah Barrayn is known for her dynamic documentary and portrait photography. She recently published a monograph with support from the Magnum Foundation called We Are Present: 2020 in Portraits, a year-long visual account that chronicles the Covid pandemic, Black Lives Matter demonstrations and a volatile election season. For Barrayn – an African American with southern roots – the New York of today isn’t dissimilar to what she witnessed as a child attending her neighborhood mosque Masjid Khalifah in Brooklyn. “I grew up in the 70s and 80s around organizers, people in city council, people coming to speak at my masjid, my masjid collaborating with some of the churches in the neighborhood.” she says. “It was always organizing, all the time.”

The patrons

Deana Haggag & Kashif Shaikh

As the head of the Mellon Foundation’s arts and culture program, Deana Haggag runs one the US art world’s most prestigious funding sources. She didn’t find an organized Muslim cultural community when she first came to New York, but that’s changed in recent years – and she’s been at the center of the change. “We saw so much anti-Muslim sentiment in the aftermath of October 7 people just naturally kind of gravitated towards one another,” she says. “It changed my life, the texture of my work and how I operate.” In 2024, Haggag co-hosted an Eid-al Fitr banquet that became a milestone event for the city’s Muslim luminaries and allies. “We just started modeling what would happen in our home countries – celebrate together, gather and break bread with Muslims and non-Muslims alike. I think bringing some of that to our New York felt meaningful and sort of dulled the loneliness.”

Kashif Shaikh originally co-founded Pillars Fund in 2010 as a philanthropic fund for Muslim NGOs. Since then, Pillars has evolved into an incubator and funder of emerging Muslim creative talent, with Riz Ahmed, Ramy Youssef, Mahershala Ali and Bisha K Ali among its advisers. Shaikh says it’s been overwhelming to see the Muslim talent that Pillars has supported get platformed by Netflix and be shortlisted for an Oscar. “We’re starting to really get our due,” he says. “Getting noticed for all of these incredible contributions, the art that we’re creating.”

The musician

Arooj Aftab

Very little about the Grammy-award winning musician Arooj Aftab is conventional. A Pakistani, Brooklyn-based singer and composer, her sound combines jazz, South Asian classical music and Sufi poetry. As a teen, she was a central figure in Pakistan’s indie music scene. But New York beckoned. “It has this energy, this magnetism, this individualistic society where you can be whoever you want to be,” she says. Today, she performs all over the world (including a recent residency at the city’s famed Blue Note jazz club) and is the first Pakistani woman to nab a Grammy. She feels this moment provides some relief from the weight of anti-Muslim discrimination. “All the prejudices are just so backwards,” she says. “They’re boring.”

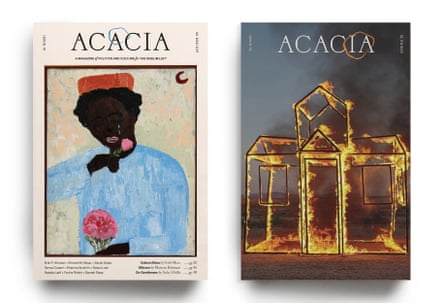

The magazine (ACACIA)

Hira Ahmed, Maryam Adamu & Arsh Raziuddin

Acacia magazine launched in Jan 2024 as “a political and cultural magazine that brings together writers, thinkers, and artists of the Muslim left”.

Hira Ahmed – a former tenants rights attorney and Acacia’s founder and editor-in-chief – pursued the idea after realizing that there weren’t many forums for Muslim intellectuals and creatives. “We don’t have an opportunity to address issues that exist within our community amongst ourselves,” she says. To help raise funds, she brought in Maryam Adamu as publisher – a fellow lawyer who recruited a handful of philanthropists to help get Acacia off the ground.

Since launch, the magazine has explored the intersection of queerness and Islam, the legacy of the War on Terror, the many impacts of Gaza on Muslim life outside the region, and much more. “I’ve been sort of bowled over by the talent of the people who contribute,” says Adamu. Acacia’s elevated visual aesthetic is the brainchild of creative director Arsh Raziuddin – also an in-demand book cover designer and illustrator. (Her recent designs include Salman Rushdie’s Knife and Jennette McCurdy’s Half His Age.) For this team, the magazine provides a journalistic home that had been hard to come by. “Places are not set up for us,” says Raziuddin. “So we have to carve out other ways.”

Credits

Digital design director Rich Cousins

Design and development Harry Fischer

4 weeks ago

27

4 weeks ago

27