On a recent Saturday afternoon in an informal settlement in the Ugandan capital, Kampala, dozens of young men sat on benches in a dark shack to watch a bootlegged version of the Hollywood comedy-horror film The Monkey.

As the English-language action unfolded on the screen, a voiceover translation in the Bantu language Luganda by VJ Junior – one of Uganda’s top video jockeys – boomed into the room.

VJs, who liberally translate movies and TV shows for local audiences, have become an integral part of TV and film culture in rural and low-income areas of the east African country.

Part-interpreters, part-comedians, they often simplify scripts and frame them in a familiar context – for instance by changing characters’ names to those of local people or replacing western concepts with Ugandan examples.

In one scene in The Monkey, a father explains his absence from his son’s life. “That’s why I stay away, because I come with all sorts of weird baggage and I don’t want you to have to deal with that,” the character says. “Like bad stuff … like evil stuff … stuff that I got from my dad and I don’t wanna pass it on to you.”

In VJ Junior’s retelling, he says: “The reason I didn’t want to be with you is because I carry a heavy burden – spiritual afflictions, demonic forces, curses and other things I inherited from my father.”

VJs also deploy humour, exaggeration and their own sound effects, occasionally veering off-script entirely – talents that have made some of them among the country’s most sought-after entertainers.

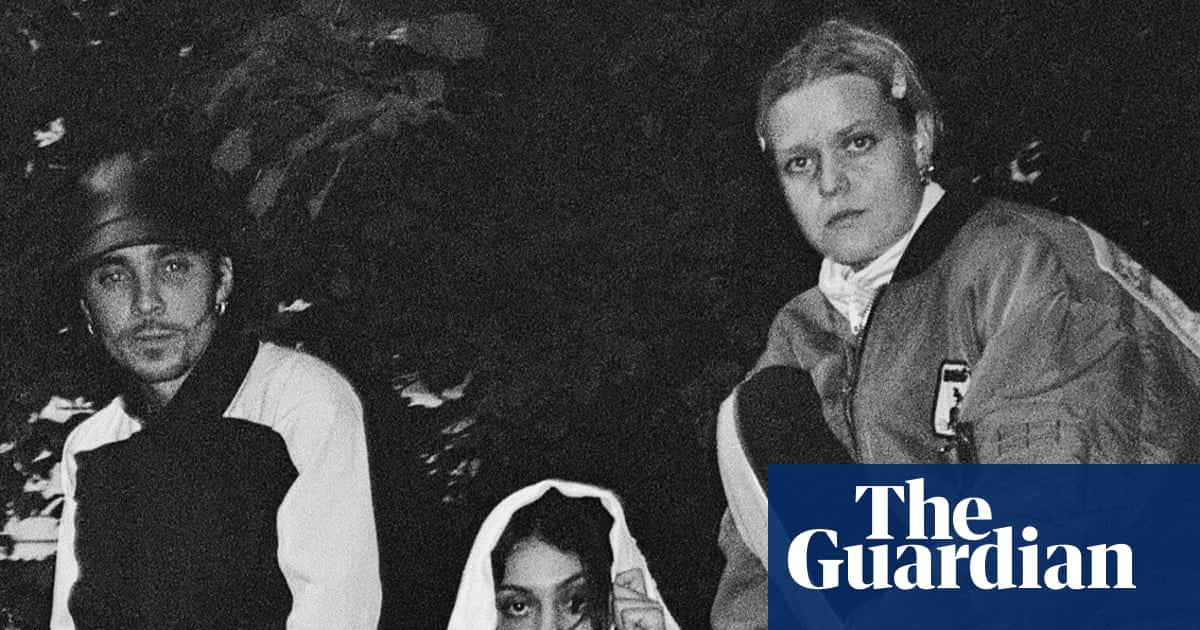

Growing up in Kampala in the 1990s, VJ Junior, whose real name is Marysmarts Matovu, was a film buff who loved watching Hollywood movies translated by VJs.

He got into the trade in 2006, inheriting a recording studio from his elder brother VJ Ronnie when he relocated to the US to pursue film-making. In his own words, his VJ debut, Rambo III, “lacked a bit of skill”, but he went on to master his craft by studying the works of pioneers like KK the Best and VJ Jingo.

VJ Junior’s breakthrough came in 2009 when he translated The Promise, a Filipino soap, for the local station Bukedde TV. “It was a big hit and it made a big brand for me,” the 40-year-old said. “People started believing in my work.”

Ronnie’s Entertainment, a video store in Katwe neighbourhood, was a beehive of activity: shoppers perused shelves stacked with thousands of VJ DVDs while employees sat in front of computers copying movies to waiting customers’ flash disks. DVDs sell for 2,000 Ugandan shillings (£0.41), and titles copied to flash disks go for 1,000 shillings.

The shop’s proprietor, Ronald Ssentongo, said he sold hundreds of films and TV shows every day, and that some of the most popular titles included Marvel movies and the TV shows Prison Break and 24. “These titles are already available in their original English versions, but people don’t watch them,” he said. “They’re waiting for VJ Junior’s translation.”

after newsletter promotion

Video jockey culture in Uganda evolved from the colonial-era practice of evangelists giving a person a microphone to translate Christian videos for local people. As foreign movies on VHS became more available in the 1980s, video halls started popping up. To overcome the language barrier, video hall proprietors hired VJs to translate them to local languages in real time.

As technology advanced, VJs moved to distributing their work on VHS tapes, VCDs, and now DVDs and flash disks. Many have created websites for viewers to stream and download their material upon subscription.

The industry is growing in other ways too. Some VJs are increasingly dubbing Ugandan movies and TV shows, and new VJs have emerged to translatie to languages other than Luganda, the most widely spoken in the country.

By localising foreign films and TV shows and helping Ugandans make sense of them, VJs make audiences feel valued, said John-Baptist Imokola, a lecturer at Makerere University who has researched the work of VJs. “They feel appreciated, they feel recognised and they feel known,” he said, though he also warned of the risk of oversimplified translations that deny audiences an understanding of the themes and messages the original films intended to convey.

VJs and their distributors occasionally have run-ins with authorities over copyright infringement, with police sometimes raiding video stores and confiscating DVDs and equipment used to copy films. VJ Junior said the copyright issue was a big challenge for his business and that it was “very difficult” to get the rights to dub foreign films.

VJ Junior, who described the role of a VJ in Ugandan society as “helping people understand movies, entertaining them, and inspiring them”, said he dubbed an average of 10 films or TV episodes every week.

“You have to do research, you have to be informed and you have to be educated,” he said of the skills required to do his job. “The industry is growing and, so is demand.”

3 months ago

109

3 months ago

109