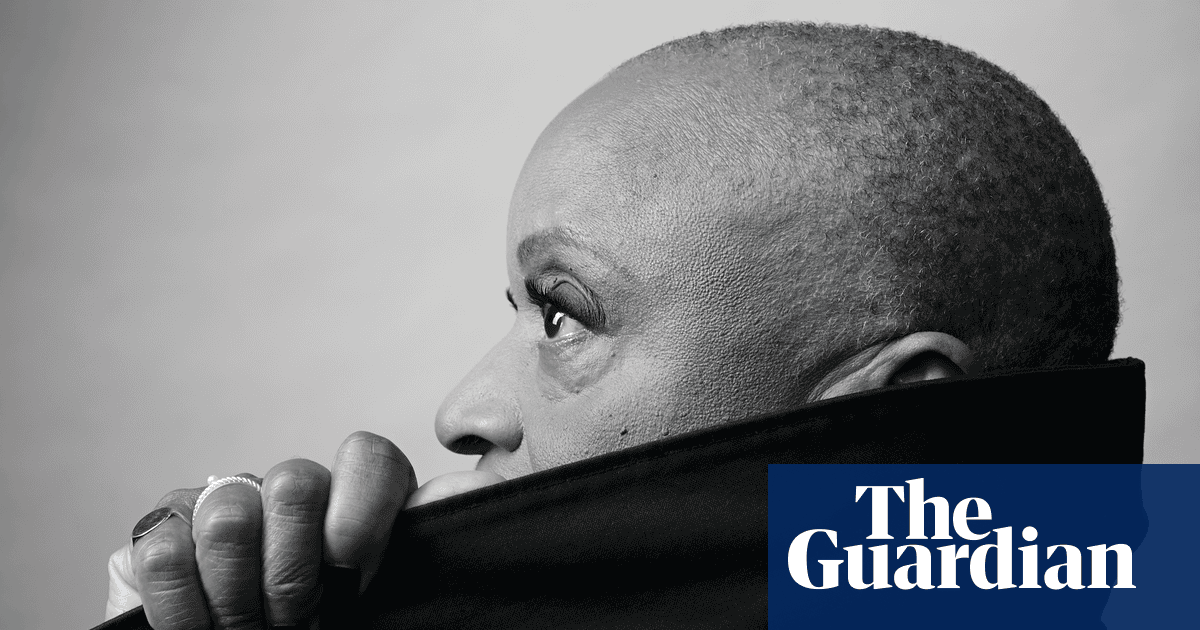

In the conference room of a hotel in Kensington, the man who would be France’s next head of state is sharing his views about Brexit. Microphone in hand, Gabriel Attal is here to meet activists and expatriates. Once 270,000 strong, London’s French community has dwindled in recent years. The 36-year-old leader of Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party is doing his best to gee them up.

“We are waking at the moment from a long sleep when we talk about relations between France and the UK,” he says. In the face of war in Ukraine and turmoil in the US, old alliances are reforming. “Many thought the channel would become an ocean. And that all the ties that bound us had to be cut. But we are emerging from this sleep because in some measure we are forced to.”

In two years, when the term of his mentor, Macron, comes to an end, Attal is positioning himself to lead their centrist party into battle against Marine Le Pen’s populists. If he succeeds, he would take not only Macron’s crown but also his record as France’s youngest-ever president. For now, he is launching himself on the international stage, with visits to Ukraine, Israel and later this year to Africa.

In London last week, he was accompanied by his bodyguards and a team of smartly dressed young men, staffers and parliamentarians, graduates like him of France’s elite Sciences Po university. During his visit he called on the former UK prime minister Tony Blair and laid a wreath at the statue of the French wartime leader Charles de Gaulle. On Wednesday evening in Kensington, in the heart of London’s French quarter, he addressed his audience with the confidence and lyrical flow that have earned him the nickname of “le snipeur des mots” – the word sniper.

“Liberty was given by the proponents of Brexit as a reason why they had to leave the European Union. But being free is not being able to choose the colour of your passport. It is about being able to choose the face of your destiny.”

Attal’s rise through the ranks has been a succession of firsts. At 29, he became the country’s youngest postwar minister after being put in charge of education. At 34, in January 2024, he became prime minister, another record. He was cheered in the national assembly when he spoke of his pride at being the first out gay man to hold the office. It was a short-lived success – Attal’s term came to a premature end last September after Macron called a snap election in a bungled attempt to see off the hard right.

Dusted off and back in the saddle, he has not officially declared his candidacy for the presidential race in 2027, but he is fairly open about his intentions. Asked whether he would stand during an interview with the Guardian, Attal replied: “J’y travaille.” (I’m working on it).

The interview was supposed to be in person but London traffic intervened, and Attal, after a polite apology, spoke by phone from a car as he raced to catch the Eurostar train back home. His focus for now, he said, was on policy and party renewal. Renaissance has been churning out papers, with proposals to curb immigration and tackle teenage screen addiction. The party wants a social media ban for under-15s, and an internet curfew between 10pm and 8am for those under 18. Videos would switch to black and white after half an hour’s viewing. “I’m working with my party, Renaissance. I want us to have a project and a candidate. Many candidates for the presidency today don’t have a project.”

Gabriel Attal de Couriss followed a well-worn path through elite schools into the ranks of the political class. The son of Yves Attal, a lawyer and film producer, and Marie de Couriss, a film production worker from a family of traders who settled in Russia then Ukraine following the Bolshevik Revolution. He thrived despite the disruptions of divorce and his father’s early death from cancer. After attending the exclusive École alsacienne private school, he studied public affairs at Sciences Po, the Paris university whose graduates include Macron and and a long list of presidents and prime ministers before him.

His social politics are a mix of liberal and authoritarian. He voted to make access to abortion a constitutional right, but has legislated to curb the wearing of clothes associated with Islam. As education minister he banned the abaya for girls and the qamis for boys in schools.

Last month, Attal proposed to go a step further, by outlawing headscarves in public for girls under 15. The reaction was swift and negative, with accusations he was just looking to grab headlines, and members of his own party distanced themselves. The Renaissance education minister expressed “the most serious doubts” about asking police to question or even caution children in the street.

Attal rejects the notion that designating the clothing worn by children as the latest culture-war battleground puts them at risk.

“I think that what puts a little girl in danger is to impose on her an outfit that consists in inculcating to her the idea that she is inferior to man and that it is impure for her to discover her face.”

On immigration, he wants closer cooperation with the UK. He says Macron’s state visit to Britain next month, during which the president will stay at Windsor Castle, will be an opportunity for bilateral talks.

“I think there are several subjects which are absolutely major on which we must move forward,” he said. He listed defence – “the United Kingdom is part of the European continent and with France is one of the two countries that has a complete army” – the economy, energy and immigration.

On the vexed question of access for UK arms firms to a new €150bn EU armaments fund, he was diplomatic.

“When it comes to EU financial instruments, they come first to support the European defence industry, and it will depend on financial participation, but I know this is being negotiated right now. I hope we can find a way to deepen the military cooperation with the UK.”

He said the next big step would be discussion on how the UK can align with a new pact for asylum and immigration that will enter into force across the EU next summer.

The agreement allows faster processing and triage of migrants at designated entry hubs. Importantly, each member state will take an agreed share of new arrivals, or pay countries of reception €20,000 to keep them.

“It is very important that we can identify the way in which this pact will be implemented in connection with the United Kingdom,” said Attal. “I remind you that there is an estimate of 30% of immigrants who come to the European continent who do so to go to the United Kingdom.”

For Ukraine, Attal wants an accelerated path to membership of the European Union. Hungary is threatening to use its veto, and farmers are worried about the continent’s largest food-producing nation flooding the tariff-free single market with cheap agricultural produce. The pushback has delayed the accession talks, which were due to begin this month.

In March, Attal hosted a summit in Paris with allies from the European parliament, and members of opposition parties in Hungary and Slovakia. They agreed to campaign for Ukrainian lawmakers to attend the parliament as observers, starting no later than 2026. Other measures included seizing the €200bn of Russian assets frozen in Europe to finance Ukrainian resistance and increasing defence budgets to 3% of domestic product.

“We have a situation that is obviously unprecedented, with a country attacked, at war, which wants to join the European Union. And therefore the procedure itself must be adapted.”

Is he in favour of the parallel negotiation solution, which would allow progress without needing Hungary’s approval, being suggested by some officials in Brussels? It seems so. “I think all channels must be used,” Attal said.

He spoke with the confidence of a man adept at finding his way around obstacles. The interview came to an end as his car approached St Pancras station. A call to the French embassy, and Attal and his bodyguards were whisked through security, making the 11.30am back to Paris with minutes to spare.

2 months ago

33

2 months ago

33