Craig was a runaway when I first met him. Missing from a local children’s home, he spent his days hanging out in Nottingham city centre. He had just turned 13 and he was tall for his age, easily recognisable with his blond hair, but he seemed invisible to the authorities.

No one was looking for him or the other dozen children who congregated on the market square. Most of them had absconded from care, some were dodging school. A few, like Craig’s mate Mikey, just didn’t bother going home. The youngest runaway, Mark, claimed he’d been missing from foster care for months and had spent his 12th birthday on the run. They were glad to have found each other and for a week or so they slept together in an alleyway. Craig organised bedding. He had picked up some tips from the experienced rough sleepers, he told me, as he collected cardboard he’d stored behind a bin. “Keeps the cold off your bones,” he said, without confidence. That was his first taste of being homeless.

It was 1998 and I was in Nottingham filming Staying Lost, a documentary series for Channel 4. The number of runaways in the UK was at crisis point. A Children’s Society report estimated that 100,000 children ran away every year. Our series set out to follow some, like Craig, who survived on the streets, existing outside the system. We documented his life as he stumbled from one precarious situation to the next. On the face of it, he seemed unfazed by the chaos around him. He was often quiet, watching as street dramas played out in front of him. It was difficult to read what he was thinking and just how lost he felt.

Once in a while, Craig would catch the bus four miles up the road to the 1970s estate where he grew up. I went there with him one day, half hoping I would find out the truth about why he’d ended up in care in the first place. Craig was pleased to show me round his “manor” as he called it. Teenagers cruised up and down on bikes that were far too small for them and there were trainers strung up over telephone wires. “Thrown up there for a laugh. There’s not much to do round here,” Craig admitted, although he seemed genuinely pleased to be back.

We went into his mum’s. And if I was expecting some clues to his past the carefully wiped surfaces and dusted ornaments gave nothing away. The house was full, he explained to me. His sister and her baby lived there although his older brother had his own place now. His mum made me a cup of tea, but had little to say to her youngest son. According to her, he was “a nightmare” and his antics, as she called them, were too much for her. He’d had his last chance and she’d put him in care. No one could deal with him, she told me. It was unclear how much anyone had tried.

Our visit was short lived. If he’d ever had a room, it was no longer available. In fact, there was no sign left that he’d ever lived there. No point in sticking around when you don’t feel wanted. So 13-year-old Craig jumped on the bus back to town and began the search for where he would sleep that night.

The novelty of a cardboard mattress had worn thin and Craig started to seek out more sheltered places to hide. He called me once from a half-derelict squat near the station. A bloke called Jock was letting him crash in an old armchair but it was too noisy to sleep. Mates of Jock’s turned up unannounced at all hours, with unexplained bloody noses and unpredictable tempers.

When the weather was OK Craig tried “camping out” on the Forest recreation ground but it was too “on top” as he called it. The nearby red-light district was busy and punters cruising past made for an uneasy atmosphere. Shadows slipped in and out of the headlights and Craig knew that girls from the children’s homes were working there. He’d heard stories of young boys selling sex in the public toilets. It was the 90s and exploited children were still prosecuted and labelled as “child prostitutes” or “rent boys”. After a couple of nights, Craig headed back into town.

Every now and again the police would come across Craig in the town centre and take him back to the children’s home. Protesting half-heartedly, he would allow himself to be put in the back of the van. A few hours later he’d be back. Nobody at the home stopped him leaving. And nobody asked what he was running from.

“He was trying to escape,” Jodie Young told me recently. “You risk something worse happening to you when you run off but you still feel anywhere’s better than care.” Jodie had been spat out of the care system herself and at 18 she was addicted to heroin, putting in long hours begging near the Midland Bank cashpoint. She became an unlikely protector of Craig and the others, letting them stay at the flat she shared with her boyfriend, Dave, and their jack russell, Penny. “I knew they were scared,” she said. “I wanted to give them somewhere safe.”

A few years earlier, Jodie had spent some time at Beechwood House, the residential home Craig was missing from. If anyone knew why he had run, it was Jodie. Neither of them talked about life in the home. Whatever the truth was, they had an unspoken understanding to bury it. For a while, Jodie’s flat was a safe place. They had proper mattresses on the floor and sometimes bought Pot Noodles to eat together in the evening. Jodie warned the young runaways against heroin, although she was losing that battle herself. Above all, there was a feeling that everyone in the flat was in the same boat. They’d been let down by everyone whose responsibility was to care for them. It was up to them to look out for each other.

By the time filming was coming to an end, this temporary stability was over. Jodie and Dave had been evicted, the little dog, Penny, taken away and the flat boarded up. Now 14 and a good foot taller, Craig once more found himself with nowhere to go. Even the police had given up taking him back to care. It felt like a dangerous crossroads, so I took a chance and suggested a visit to his mum’s. After an awkward start she grudgingly agreed that he could stay on the sofa for a while. Rules were laid down, promises made and a spare duvet was found. But I didn’t hold my breath. Things didn’t work out and soon enough Craig called letting me know he was on the move again.

For 18 months, Craig had trusted us to film the reality of his life as a runaway, when suddenly Nottingham city council stepped in claiming they were responsible for him and we had no right. They sought an injunction to stop the documentary from airing but after a gruelling few days being cross-examined in the Royal Courts of Justice, the judgment went in our favour. Craig was entitled to have his story told and Staying Lost was broadcast in April 2000, when he was almost 16.

I still hoped that things might turn around for him, but in the year after the film aired, the police started picking Craig up for minor crimes and before long he landed up in a young offender institution. I visited him during that first stint inside. He got me a cup of coffee from a machine in the corner of the visitors’ room. He had an idea of training to be a mechanic but first he’d have to find somewhere to live. He wasn’t sure how he’d manage that. He was almost a grown man by now, not a priority for housing. And statistics on the fate of care leavers were stacked against him. It wasn’t long before he knew his prison number by heart.

At first he was still seeing how far he could take things. When he was about 19, he came up with the idea of robbing a small supermarket by pretending he had a gun in his pocket. The terrified cashier handed over the contents of the till and he legged it with the lot. But it wasn’t Craig’s style. He was back in the morning to turn himself in. “I just couldn’t get it out of my head,” he told a friend later. “I’d scared the life out of that woman and I couldn’t live with that.”

Steven Ramsell first encountered him in 2004. “I have a memory of sitting opposite Craig in the old dingy Bridewell police station,” Ramsell, who is a solicitor advocate, told me. “He was one of the first people I represented. If you looked at the outer husk you’d see a shop thief, a pest. Yes, he’d commited a load of crime, but it was low level stuff, and it was the only thing he knew.” Craig drew the line at house burglary but had become expert at lifting phones and purses. By the time he was 25, Craig was a regular client and, according to Ramsell, almost incapable of functioning in modern society. “While I was out there I just did not know how to live normally,” Craig wrote to me in 2017 from HMP Nottingham. “I felt awkward and out of place all the time. It’s no excuse for the crimes I did. But I just don’t know where or how to start.”

There were people who tried to help him in those early years. People who remembered him as a kid let him use the shower or get his head down for a few nights. Some let him stay longer. But then Craig would “pay back the favour” by filling the fridge with stolen food, the police would turn up at the door, patience would wear out, and he’d be on his way again. “Craig is his own worst enemy,” people would say.

Over the next 10 years I often lost track of whether he was in or out. Then out of the blue I would answer my phone to an automated voice. “This call is from a person currently in a prison. All calls are recorded and may be listened to by a member of prison staff. If you do not wish to accept this call, please hang up now.” Then Craig would come on the line, explaining the complex mess of arrests and outstanding warrants, recalls and remand hearings that had resulted in him being locked up again. “How are you doing, Pam?” he would never fail to ask. And I would try to find little things to tell him, all too aware that he’d find it hard to imagine the life I led. He liked to hear where I’d been and how my family were and he knew I was relieved to hear from him.

Often, he would ask me to send another DVD copy of Staying Lost. He was proud of the film. He always said it was the only thing he’d ever really finished. He tried to show it to prison officers and volunteers on the inside. I think he hoped that by watching it they would get some idea of how much he’d been through and that maybe one day someone would come up with the answer to how he could sort his life out. But officers were neither inclined nor equipped to ponder prisoners’ life stories. “You should make a follow-up documentary on me, Pam,” he’d often say. “That’d show people what it’s like, what happened to me next.” But TV had moved on. I was told by one executive that Craig just didn’t have a “TV face”.

Time and again Craig would walk out of the prison gate with no address. He’d leave with the best intentions of going to see his probation officer. But those appointments were often fraught and filled with forms and applications he couldn’t handle. And they usually led to a dead end. So, he’d find a mate to stay with. Someone who was doing him a favour. I could sometimes hear the chaos of those places in the background if he called me. “It’s sound here,” Craig would reassure me. But things would soon unravel.

I remember how often Craig lost his few possessions, left in a hostel or at a mate’s house. There was usually a stereo, a “really good one” that he’d not been able to carry. And always a pair of trainers he’d managed to leave behind, even though the ones he was wearing were ready for the bin. During one particularly freezing winter, his stuff was lost when he was transferred between jails and he was released into a bitter morning outside HMP Hull with nothing more than the regulation sweatshirt and trackies he was wearing. I’d called the prison and tried to ask them to find clothes for Craig but as usual it was impossible to get through. It was only thanks to the resourceful and dedicated chaplaincy team that someone was able to meet him at the gate with a coat and scarf from the lost property.

No one wakes up in the morning and decides to become a heroin addict, Jodie once told me. And I’m certain it wasn’t a decision Craig made, but that’s what happened. During his longer stints in prison, he’d sometimes get on to a drug reduction programme and get clean. But drugs are easy to score behind bars, and all too often offered a way to cope. “I run back to the drugs,” Craig once wrote to me, “cos I know how to be a druggie, I know what I have to do, or have to act, where other situations I haven’t a clue. Things get too emotional for me. I even panic when I’m just attending appointments whether it’s the jobcentre or whatever I just panic in my head. I feel like I’m 13 years old again when I’m out.”

By the time he was 33, Craig had 170 offences on his record and was spending less and less time on the outside. “He was institutionalised,” Ramsell told me. He’d been round the system so many times. Any support he got was never strong enough to spark a change. “There should be another option, but there wasn’t,” Ramsell said. “And Craig always knew what was coming. Back on the merry-go-round.” So, in the spring of 2018 the door of Nottingham prison revolved for Craig again and he was back on the wing.

During the months that followed, Craig was in touch more than usual. At the time, Nottingham was one of the worst prisons in the country. It had recently been issued an urgent notification from the chief inspector of prisons – essentially, the institution has been put into special measures. The tensions that had simmered on the wings for years had finally reached boiling point. Officers and prisoners felt unsafe. Drugs, especially the noxious synthetic cannabinoid spice, were freely available. Over an 18-month period, 12 prisoners took their own lives.

“I don’t even escape my problems when I’m asleep,” Craig wrote from his cell. “I live a nightmare in the days and when I sleep. I just don’t know if I can cope no more. My head is a mess and the days are just getting worse for me. I want a rest from myself.” His phone calls became desperate, and his letters got longer. I worried if I didn’t hear from him every day. Chaplain John Seeney was instrumental in getting Craig through that sentence. “We have to hang in there with Craig,” Seeney would say to me. Every Tuesday, Craig would ask to be let off the wing to attend the prison chapel where Seeney and the small multifaith team offered a place to talk and be heard. Craig was there without fail and even started writing some poems singing the praises of the support he’d found.

And, as if by way of a small miracle, when Craig was released in early 2019, Seeney managed to negotiate him a room in a house connected to a church group in Ilkeston, a small town outside Nottingham. I travelled up on the train and he met me from the station. He’d been swimming, he told me, and he’d been to the library to try to learn how to use a computer. He had the key to his shared house on a long string and opened the door. He had milk in the fridge, and he made me a cup of tea. We spent a normal afternoon in the sunny back yard, and I still have a photo of him with a glimmer of hope in his eye.

Before I got the train home, he took me to the church where he was volunteering, helping with their daily pop-in cafe. The other volunteers, who were much older, busied themselves with an antiquated tea urn and plastic boxes full of biscuits. There was a confusion about the “tea-towel rota” and Craig stepped up and offered to take his turn. A woman handed over a plastic bag full of towels and dish cloths with a slightly quizzical look in her eye. I remember worrying as we left the church hall about whether he had a washing machine or knew how to use it.

A few weeks later, there was trouble. Rules for ex-prisoners are tough and trust is hard won. He ended up being chucked out for inviting “friends” round and throwing a kettle across an empty room. No more cups of tea. He was recalled to prison.

We often talked about that afternoon, and I always said that now he’d managed to live in his own place once, he could do it again. But although he listened, I believe he knew his chances were running out.

At 35, Craig was looking at a longer sentence than usual after the recall. On the positive side, it meant he might have access to some of the support that was unavailable during shorter stretches. A woman named Tara Tan had recently started working as an art psychotherapist in Nottingham, partly thanks to the efforts of the ever-resourceful John Seeney. The chaplain hoped that art therapy might be a good fit for Craig, helping him express things he couldn’t find words for. “He liked to use colour pencils,” Tan recalled. “He would colour in, and sometimes he would draw. But I think he used the space more for somewhere he could let out frustrations with no fear of judgment.”

At the start, Craig told me he didn’t feel anything but numb and that worried him. “I’m closed off emotionally to everything,” he told me on the phone. “That’s been as far back as I can remember.” Tan noticed this, too. “He found it difficult to open up for fear of being hurt more,” she told me. “You need to make sure you leave the sessions on a positive because you’re sending someone back to the wing knowing they’ll be locked up in their cell alone.”

Then in July 2019, while Craig was working with Tan, the independent inquiry into child sexual abuse published its investigation into how Nottingham council had responded to allegations of sexual abuse from children in care. “For decades, children who were in the care of Nottinghamshire council suffered appalling sexual and physical abuse, inflicted by those who should have nurtured and protected them,” announced Prof Alexis Jay, chair of the inquiry. “Those responsible for overseeing the care of children failed to question the extent of sexual abuse or what action was being taken.”

Beechwood House, where Craig had been placed between the ages of 13 and 14, received a special mention. Violence was common and sexually abusive staff members were allowed free rein. Children’s allegations were ignored. Beechwood had finally been shut down in 2006, seven years after Craig’s time there. It turns out that there had been an awful lot to run away from.

The last time I saw Craig in person was in autumn 2019. He invited me up to HMP Nottingham for a ceremony celebrating the end of a training course he’d completed on staying straight. In the 12 sessions he had been taught skills for “a life free from offending and drug misuse”. Although I was a bit unclear about what magic key Craig had been given to help him avoid his past mistakes, it was a proud day. John Seeney was there, of course, and Tara Tan. The governor made an appearance, and cake was served on paper plates. An ex-prisoner gave a talk about how you could turn things around, about how much was possible if you tried hard and wanted it enough. I watched Craig step up to receive his certificate as he smiled, half full of hope.

But over the next few years, fresh starts became harder and ended sooner. There was a sense that time was running out. Earlier this year, on 10 May, Craig spent another birthday behind bars. I heard from him as usual just before he was released.

“Hiya Pam, it’s me, Craig here on the pen. Well now, I’m officially 41. Just 16 more days to go till I’m back in the big wide world. I just hope it stays that way and I can finally get my life turned round …”

In that email he said he was hopeful of getting somewhere to live when he got out at the end of May. He’d had an assessment for housing a few days before and thought that with the council’s help, for once, he wouldn’t be on the streets again. And so the countdown began to another release, another clean slate. He promised to call when he got to probation to sort his benefits out. By then he’d know his new address, he said.

It wasn’t a surprise when he didn’t call. After a week or so of not hearing from him, the usual worry began. I called a few people in Nottingham to find out if anyone had seen him. No one had. So, I waited for him to show up as he always had before. Waited for him to call, probably from someone else’s phone, saying that he’d messed up his appointments or that he had no money for the bus to get to probation. Or that he’d just been sleeping for days and that he was sorry.

The call never came. On the night of 29 June 2025, Craig was found dead. A passerby found him slumped on some steps outside a house, the police told me. He was only a mile from the alleyway where he had slept rough as a 13-year-old.

It’s not clear yet which new set of statistics Craig will be added to. He will definitely be counted in this year’s homeless deaths, which numbered 1,600 last year. And he might join the UK drug deaths total, which reached 5,565 last year, the highest number since records began in 1993. It’s possible that he was a casualty of synthetic opioids. The number of those deaths has almost quadrupled in England and Wales, from 52 in 2023 to 195 in 2024. Or perhaps the drugs that contributed to his death won’t be recorded at all. The Office for National Statistics admits that figures for drug misuse are more than likely undercounted. Whatever the case, statistics like this can only explain in the narrowest way why Craig died.

I later found out that Craig had been released, that final time, into emergency accommodation, rather than the longer term residence he was hoping for. He’d been offered a bed through The Community Accommodation Service, which provides short-term housing for prisoners released with no fixed address. It’s a last resort when “nothing else has been achieved”, someone from the Probation Service told me. Craig had apparently burned most of his bridges with them. “He struggled to engage,” they said. “But there are a lot of unanswered questions.”

I emailed Steven Ramsell and told him the news. “It was a sad day in our office,” Ramsell said when he called me later. He asked about the funeral and I told him that Craig’s immediate family had opted for a public health service, which would be arranged and paid for by the council. “A paupers’ funeral,” said Ramsell. “The final tragedy in a tragic life.”

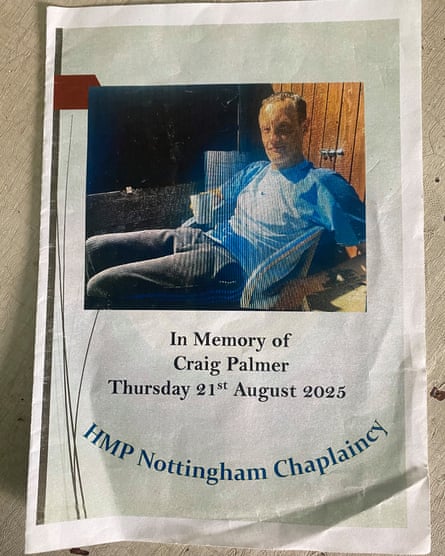

Craig’s cremation took place on 11 August. Not wanting it to go unmarked, John Seeney went and was allowed to say a few words. He told me he gave Craig’s coffin a little pat, as a goodbye from us all. Ten days later, Seeney and I organised a memorial for Craig inside Nottingham prison in the Chapel where Craig had found some sanctuary over the years. Jodie Young, Tara Tan and about 20 of the current inmates were there.

Seeney had made an order of service on the chaplaincy printer. My photo of Craig smiling in that back yard in Ilkeston was on the cover. I brought in another photo of him from when he was 13. I remember the moment it was taken. Craig was talking about blackberry picking with another runaway. Even then, it had felt so distant from the life he was living. We stood it on the chapel altar in a glassless frame.

A couple of the prisoners stood up and shared memories of Craig. One, Jayden, who remembered robbing crack houses with him, shook his head in amazement that he’d survived a chaotic life on the streets and Craig had not. We laughed as people recounted the wilder stories from Craig’s life, like the time he leapt off a bridge while being chased by police and fortunately landed on a passing train. He always maintained to the chaplain that God had scheduled it to arrive just in time.

Jodie was too upset to speak. After 30 years of heroin use, she will mark her two-year anniversary of being clean this December. She works as a drugs peer mentor. “My heart feels like it’s been smashed to pieces,” she told me quietly. “What’s the point of me volunteering at drug services and helping save people’s life when I can’t even save the people I care about?”

Craig used to say how he’d love to donate his body to science, how they’d learn a lot from him. “It’s just that I wouldn’t know anything about it, Pam,” he used to laugh. And it’s true that no stone is being left unturned to try to work out what combination of longtime drug use, poor health, despair or neglect killed him in the end. The postmortem is under way, and an inquest is planned. In an extremely unusual move, the pathologist has retained the whole of Craig’s brain to enable them to carry out a detailed examination. So many resources are being spent now that he’s gone.

In the chapel, Seeney played some music, a kind of mystical South American track which felt strangely comforting and we sat in silence with our own memories. As we got ready to leave that afternoon and officers were called to take the prisoners back to the wings I thought about how Craig would feel to see us all here. That he’d never believe how missed he is.

The best stories take time. From politics to philosophy, personal stories to true crime, discover a selection of the Guardian’s finest longform journalism, in one beautiful edition. In the new Guardian Long Read Magazine, you’ll find pieces on how MrBeast became the world’s biggest YouTube star, how Emmanuel Macron deals with Donald Trump, and shocking revelations at the British Museum. Order your copy today at the Guardian bookshop.

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48