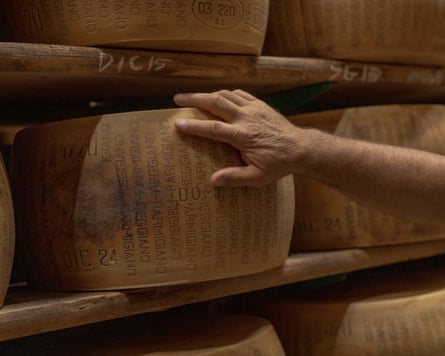

Giuseppe Alai wanders through the cellar of his dairy in Emilia-Romagna, the air filled with the smell of ageing wheels of parmesan lined up in endless rows.

Pointing towards the thick rinds wrapped around them, each bearing the distinct dotted engraving of their Parmigiano Reggiano mark of origin, he recalls an anecdote from his grandfather at the end of the second world war.

“When the American soldiers arrived in 1945 [to liberate the area from the Nazis], they gave the children lots of chocolate and in return, my grandfather gave them pieces of cheese,” said Alai. “When he explained that it was made without additives or preservatives, they couldn’t believe it – they thought it was impossible.”

-

A wheel of parmigiano reggiano.

This connection between the zesty, crumbly parmigiano reggiano – one of Italy’s oldest and most famous cheeses – and US consumer tastes has only strengthened in the decades since, with a thriving market making the country its biggest export destination outside the EU.

But Alai’s thoughts now turn to the implications of the premium delicacy, most commonly grated on to pasta or thinly shaved into salads, getting caught up in the chaos of Donald Trump’s sweeping international trade tariffs, and putting faith in its centuries-old manufacturing process.

-

One of the dairy farms supplying milk for the production of parmigiano reggiano (Reggiolo, Reggio Emilia).

The Guardian arrived at his San Girolamo dairy in Brugneto di Reggiolo, a hamlet close to Reggio Emilia, just as 1,000 litres of raw milk, taken from cows raised on local forage, was being poured into bell-shaped copper vats. The load will produce two 40kg wheels of parmigiano reggiano that will age for a minimum of 12 months, one of the rules for a cheese made exclusively in this designated area of northern Italy. Using a stencilling band, the rind is engraved with the brand, the dairy’s identification number and month and year of production within the first few hours of the wheel’s formation.

-

The production of parmigiano reggiano inside the San Girolamo dairy.

-

The stamps used for marking parmigiano reggiano inside the San Girolamo dairy.

The visit occurred a few weeks after the US president had reached a trade tariff agreement with Brussels. The deal imposed a 15% cap on most exports from the EU to the US – modest compared with the 30% Trump originally threatened but still a significant hike for most Italian exporters.

The case for Alai and his fellow parmigiano reggiano producers is somewhat unique as the agreement simply meant they reverted to the same duty paid since the mid-1960s. But only after being forced to temporarily grin and bear 25% while the deal was being thrashed out, leading to a reduction in orders owing to the stockpiles amassed by importers in the US even before Trump announced his “liberation day”in April.

“It’s too early to say what the impact of those four months will be due to the surplus [of orders] in the past,” said Alai. “But there was a lot of concern because producers risked sending orders not knowing if they would arrive or how much the tariff would be by the time they got there.”

-

Copper vats used in the manufacture of parmesan at the San Girolamo dairy.

-

Moulds are then used to form wheels.

While the US-EU agreement brought some relief, worries persist about the long-term impact on trade with the US, Alai said, especially when combined with a 13.5% devaluation of the dollar against the euro, which increases the price paid by US consumers.

“Now we fear the currency exchange rate more than the 15% tariff,” he added.

Still, he spares a thought for his cheesemaking counterparts across the border in Switzerland, who’ve been dealt a far harsher blow.

-

The parmesan cheeses in metal moulds to give the wheels their distinctive shape.

Just as the ink was drying on the EU deal, Italy’s northern neighbour was thrown into turmoil after Trump inflicted a staggering 39% on Swiss imports – the fourth highest imposed on any country, behind Syria (41%), Laos and Myanmar (40%), India and Brazil (both 50%).

A peaceful country that ordinarily stays out of global conflicts, the feeling of bewilderment was palpable even on the cross-border train journey between Milan and Lausanne. Rolling his eyes, one Swiss passenger accused the EU of “surrendering” to Trump. “Nobody is brave enough to stand up to him,” he said. Others saw it as a punishment for Switzerland’s wealth and innovative business prowess.

-

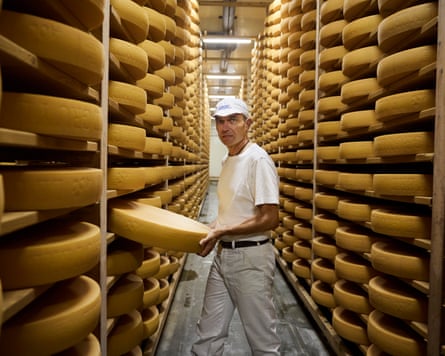

A Gruyère-producing fromagerie in Peney-le-Jorat, Switzerland.

From Lausanne, the Guardian travelled to Peney-le-Jorat, a village in the canton of Vaud, to meet René Pernet, a producer of Gruyère, another renowned wheeled cheese with a protected status, a rich history and strong exports to the US, where it is a favoured ingredient in high-end sandwiches or as a topping for crackers.

Pernet – whose Gruyère dairy, called Haut-Jorat, was also passed down through the generations – is still reeling. “There is a lot of frustration, also because we are not on an equal footing,” he said. “The EU gets 15% and we get 39%. We call the US a democracy, but for me this is not democracy – there is one person who makes arbitrary decisions. It’s irrational and feels like a punishment.”

The immediate reaction to the tariff was a sharp reduction in orders from Gruyère’s US importers, who are also not obliged to pay a penalty. Furthermore, there are fears about the effects on the entire Gruyère supply chain, from the alpine cows that provide the milk to those who work year-round to produce the cheese.

But now that the decision is made, Pernet believes Gruyère makers need to let go of their anger and try to come up with dynamic solutions. “We are strong, we have a good product, and we need to find new ways to promote it, even in our local market,” he said.

-

René Pernet with his Gruyère.

The producers’ association, Interprofession du Gruyère, based in the town of Gruyères, is mostly charged with that task.

The association estimates that annual exports to the US, which currently average 4,000 tonnes, could drop by 1,000 tonnes, reducing revenue by up to 15m Swiss francs (£14m).

“The duty is catastrophic because it has a huge impact on the prices that US consumers will have to pay,” said Olivier Isler, manager of the association. “Then there is the whole exchange rate issue.”

-

Gruyère cheese making.

The association’s first response was to reduce production to cope with the decrease in demand and to devise new ways of promoting the product in the US in order to mitigate the effects of the higher prices. “But we also need to think about whether the US will remain a priority market for us or whether we need to evolve and focus on other markets,” said Isler.

Parmigiano reggiano’s consortium has also come up with novel ways to counter the impact, including promoting the brand by sponsoring the New York Jets American football team and creating a US-based corporation that will work with universities and retail chains on educational and training initiatives.

-

The Gruyère cheeses in storage.

Parmigiano reggiano and Gruyère hail from a similar heritage, and while they are friendly rivals on the cheese competition circuit, their taste, texture and culinary uses clearly distinguish them in the market. But there is one commonality which Alai is confident will help them both maintain US custom despite the threat of cheaper, locally-made copycat versions, and that is the same thing that amazed the second world war soldiers: the all-natural recipe.

“There are very few cheeses in the world made without additives and preservatives,” said Alai. “For some countries, this is unbelievable, but it’s the most important thing we need to make clear wherever we export.”

3 months ago

50

3 months ago

50