Fifty years ago, Cabaret Voltaire shocked the people of Sheffield into revolt. A promoter screamed for the band to get off stage, while an audience baying for blood had to be held back with a clarinet being swung around for protection. All of which was taking place over the deafening recording of a looped steamhammer being used in place of a drummer, as a cacophony of strange, furious noises drove the crowd into a frenzy. “We turned up, made a complete racket, and then got attacked,” recalls Stephen Mallinder. “Yes, there was a bit of a riot, and I ended up in hospital, but it was great. That gig was the start of something because nothing like that had taken place in Sheffield before. It was ground zero.”

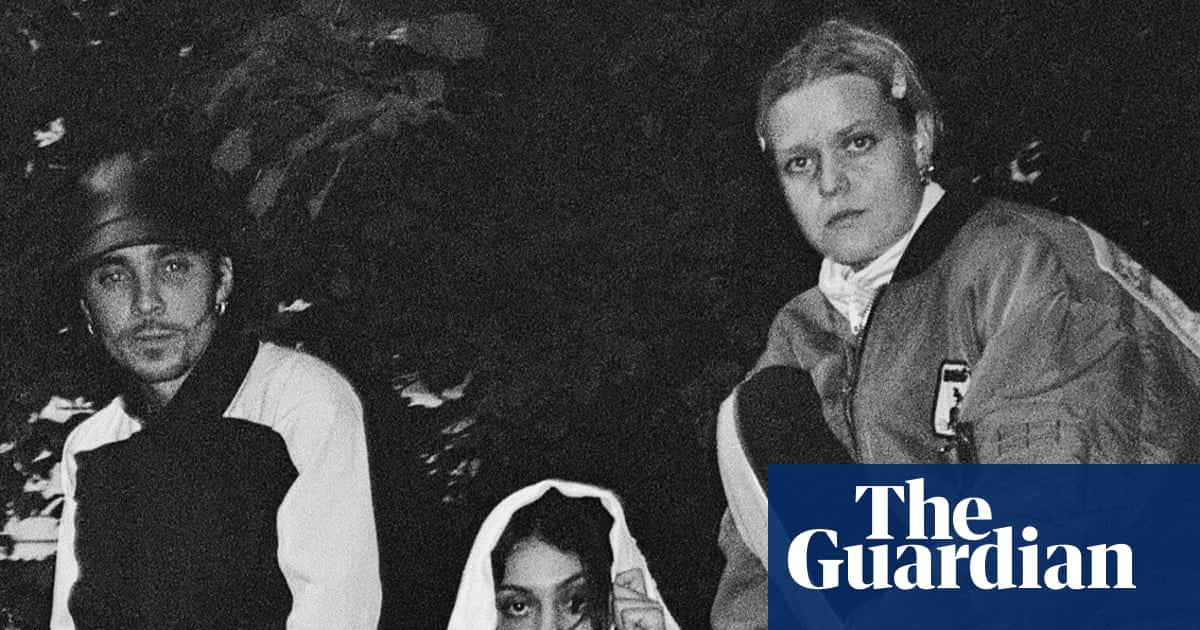

Mallinder and his Cabaret Voltaire co-founder Chris Watson are sitting together again in Sheffield, looking back on that lift-off moment ahead of a handful of shows to commemorate the milestone. “It is astonishing,” says Watson. “Half a century. It really makes you stop, think and realise the significance.” The death in 2021 of third founding member Richard H Kirk was a trigger for thinking about ending things with finality. “It’ll be nice if we can use these shows to remind people what we did,” says Mallinder. “To acknowledge the music, as well as get closure.”

It’s impossible to overstate how ahead of their time “the Cabs” were. Regularly crowned the godfathers of the Sheffield scene, inspiring a wave of late 1970s groups such as the Human League and Clock DVA, they were making music in Watson’s attic as early as 1973. Their primitive explorations with tape loops, heavily treated vocals and instruments, along with home-built oscillators and synthesisers, laid the foundations for a singular career that would span experimental music, post-punk, industrial funk, electro, house and techno. “There was nothing happening in Sheffield that we could relate to,” says Mallinder. “We had nothing to conform to. We didn’t give a fuck. We just enjoyed annoying people, to be honest.”

Inspired by dadaism, they would set up speakers in cafes and public toilets, or strap them to a van and drive around Sheffield blasting out their groaning, hissing and droning in an attempt to spook and confuse people. “It did feel a bit violent and hostile at times, but more than anything we just ruined people’s nights,” laughs Mallinder, with Watson recalling a memory from their very first gig: “The organiser said to me after, ‘You’ve completely ruined our reputation.’ That was the best news we could have hoped for.”

Insular and incendiary, the tight-knit trio had their own language, says Mallinder. “We talked in a cipher only we understood – we had our own jargon and syntax.” When I interviewed Kirk years before his death, he went even further. “We were like a terrorist cell,” he told me. “If we hadn’t ended up doing music and the arts, we might have ended up going around blowing up buildings as frustrated people wanting to express their disgust at society.”

Instead they channelled that disgust into a type of sonic warfare – be it the blistering noise and head-butt attack of their landmark electro-punk track Nag Nag Nag, or the haunting yet celestial Red Mecca, an album rooted in political tensions and religious fundamentalism that throbs with a paranoid pulse.

Watson left the group in 1981 to pursue a career in sound recording for TV. Mallinder and Kirk invested in technology, moving away from the industrial sci-fi clangs of their early period into grinding yet glistening electro-funk. As the second summer of love blazed in the UK in 1988, they headed to Chicago instead – to make Groovy, Laidback and Nasty with house legend Marshall Jefferson. “We got slagged off for working with Marshall,” recalls Mallinder. “People were going, ‘England has got its own dance scene. Why aren’t you working with Paul Oakenfold?’ But we’re not the fucking Happy Mondays. We’d already been doing that shit for years. We wanted to acknowledge our connection to where we’d come from: Black American music.”

This major label era for the group produced moderate commercial success before they wound things down in the mid-1990s. But in the years since, everyone from New Order to Trent Reznor has cited the group’s influence. Mallinder continued to make electronic music via groups such as Wrangler and Creep Show, the latter in collaboration with John Grant, a Cabs uber-fan.

Watson says leaving the group was “probably the most difficult decision I’ve ever made” but he has gone on to have an illustrious career, winning Baftas for his recording work with David Attenborough on shows such as Frozen Planet. He recalls “the most dangerous journey I’ve ever made” being flown in a dinky helicopter that was akin to a “washing machine with a rotor blade” by drunk Russian pilots in order to reach a camp on the north pole. On 2003 album Weather Report, Watson harnessed his globetrotting field recording adventures with stunning effect, turning long, hot wildlife recording sessions in Kenya surrounded by buzzing mosquitoes, or the intense booming cracks of colossal glaciers in Iceland, into a work of immersive musical beauty.

When he was at the Ignalina nuclear power plant in Lithuania with Oscar-winning composer Hildur Guðnadóttir, recording sounds for the score to the 2019 TV series Chernobyl, he couldn’t help but draw parallels to his Cabs days. “It was horrific but really astonishing – such a tense, volatile, hostile environment,” he says. “But it really got me thinking about working with those sounds again, their musicality and how it goes back to where I started.”

after newsletter promotion

Mallinder views Watson’s work as a Trojan horse for carrying radical sounds into ordinary households. “The Cabs may have changed people’s lives but Chris is personally responsible for how millions of people listen to the world,” he says, with clear pride. “And one of the things that helped make that happen was the fact that he was in the Cabs, so through that lens he opened up people’s ears.” Watson agrees, saying Cabaret Voltaire “informed everything I’ve ever done”.

Watson’s field recordings will play a part in the upcoming shows: he’ll rework 2013 project Inside the Circle of Fire, in which he recorded Sheffield itself, from its wildlife to its steel industry via football terraces and sewers. “It’s hopefully not the cliched industrial sounds of Sheffield,” he says, “but my take on the signature sounds of the city.” These will be interwoven with a set Mallinder is working on with his Wrangler bandmate Ben “Benge” Edwards as well as longtime friend and Cabs collaborator Eric Random. “We’ve built 16 tracks up from scratch to play live,” says Mallinder. “With material spanning from the first EP” – 1978’s Extended Play – “through to Groovy …”

Mallinder says this process has been “a bit traumatic – a very intense period of being immersed in my past and the memories that it brought, particularly of Richard. This isn’t something you can do without emotion.” Mallinder and Kirk were not really speaking in the years leading up to his death, with Kirk operating under the Cabaret Voltaire name himself. “Richard was withdrawn and didn’t speak to many people,” says Mallinder. “And I was one of those people. He wanted to be in his own world. It was difficult because I missed him and there was a lot of history, but I accepted it.”

There will be no new music being made as Cabaret Voltaire because, they stress, tsuch a thing cannot exist without Kirk. Instead, it’s a brief victory lap for the pair, a tribute to their late friend, as they sign off on a pioneering legacy with maybe one last chance for a riot. “Richard would probably hate us doing this but it’s done with massive respect,” Mallinder says. “I’m sad he’s not here but there’s such love for the Cabs that I want to give people the opportunity to acknowledge what we did. You can’t deny the music we made is important – and this is a way to celebrate that.”

3 months ago

57

3 months ago

57