Tamsin met Mike in the summer of 2022. He was a mechanic in a garage that she walked past twice each day between home and work. After a while, he’d call out “good morning” or “good evening” and she’d wave and smile back. Then the exchanges got a little longer. (“Hard day?” “Looking forward to dinner?”) Six months later, Mike and Tamsin exchanged numbers.

Within two years, her life was wrecked. She had left her marriage, lost her home, quit her job, and sold her car and her phone, spent all her savings and racked up tens of thousands in debt. (Under her current repayment plan, it will take another eight and a half years to pay back her creditors.) Tamsin’s story seems scarcely credible and she is mortified to have to tell it. She stumbles through, piles of notes on her lap and a support worker from Victim Support at her side. Every few minutes, she breaks off to say, “It sounds so stupid”, “I sound like an absolute nutter” or “Where was my head?” In truth, she spent two years in the company of a psychopath, a master manipulator. He is in prison now, serving a 22-year sentence, but not for romance fraud, or anything involving Tamsin. Her experience, police have told her, “would not stand up in court”.

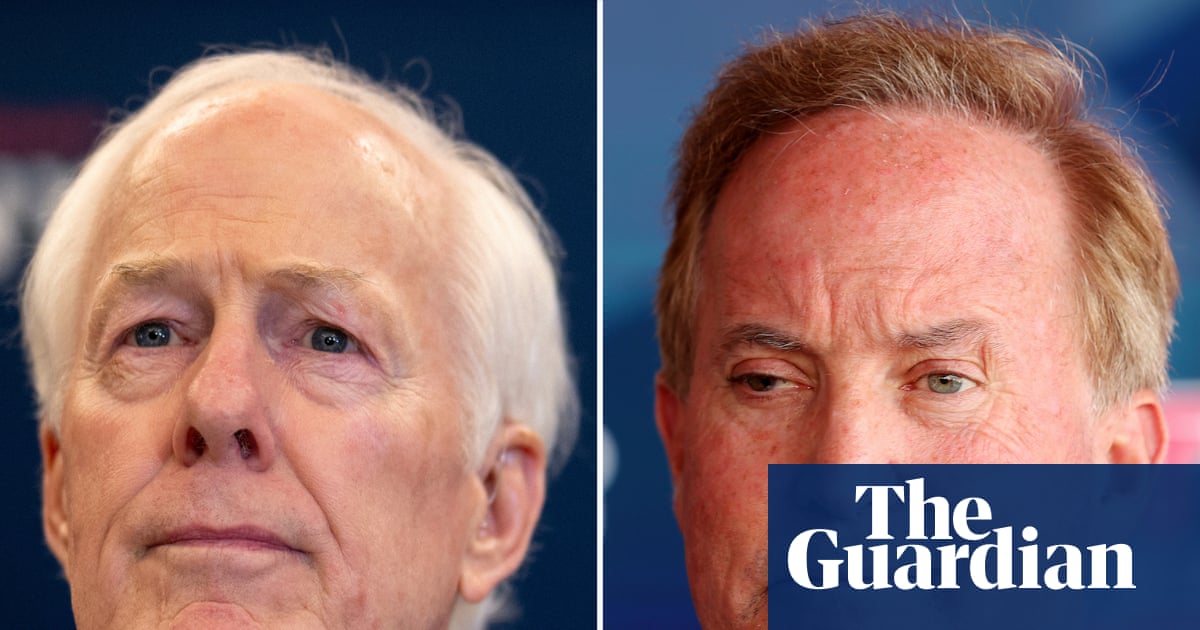

There has, however, been some progress in the understanding of “in-person romance fraud”, with the recent conviction of Nigel Baker. His 17-year sentence, for fraud by false representation, is believed to be the longest ever for this crime. Baker targeted single mothers, divorcees, and women who had been recently bereaved, including a divorced police officer and mother of two, and an accountant. He lured them into non-existent “investment schemes” and persuaded them to take out loans to help him through various invented personal crises, causing bankruptcy and a suicide attempt. There were five victims in the court case, who lost more than £900,000 between them, but police now believe there to be many more, with Baker’s crimes stretching back to the 90s. One victim reported him in 2016, but was told that this was a “civil matter”. It took four years of pushing before she found a detective to take on the case.

Anna Rowe, co-founder of the romance fraud support organisation and thinktank LoveSaid, is not at all surprised. Rowe co-founded LoveSaid in 2022 with Cecilie Fjellhøy, a victim of fraudster Simon Leviev, who was convicted of fraud, forgery and theft in 2019, and whose story was told in the Netflix documentary The Tinder Swindler. The two women are currently assisting 75 to 100 victims of romance fraud each week – including “romances” that took place entirely online, and those that took place in real life (or “in-person”). “We’ve been banging the drum about ‘in-person romance fraud’ for the past five years,” says Rowe. “When we started, we had so many women come forward to say that they’d been told by police that it was a civil matter. The typical attitude from police has been, ‘Your boyfriend lied to you – that’s not really a crime. You chose to give money to a love rat. It’s a relationship gone bad.’ Slowly, slowly, we’re seeing lines of inquiry open up. Instead of turning victims away, we want police to take five and ask questions. Why was the relationship created? Why did they say they needed money? Can you confirm it?”

There have been other recent cases. Christopher Harkins posed as a successful businessman when matching with women on dating apps, then used various methods to extract money from them. In total, he admitted to defrauding nine women out of £214,000. Harkins was also found guilty of multiple sexual offences, including rape. “You’ll find, unsurprisingly, that perpetrators of in-person romance fraud are usually career criminals and often have long histories of other crimes,” says Rowe. Though Harkins’ conviction was in 2024, many women had reported him over the years to no effect, at least one as far back as 2012.

There have been other successful prosecutions. In 2023, David Checkley was jailed for 11 years after conning at least 10 women out of hundreds of thousands of pounds. He had been convicted of similar offences in 2010 – and before that, in 2002, he was jailed for false imprisonment and conspiracy to commit grievous bodily harm. In another case, Cieran McNamara was sentenced to seven years in 2024 for swindling more than £300,000 from four women.

According to Rowe, most of the methods used for in-person and online romance frauds are the same. “We see the same patterns every time,” says Rowe. “It’s the grooming, the absolute love bombing, where the fraudster finds out everything about you and mirrors it back to create that perfect soul mate,” she says. “Then it’s the trauma bombing – getting your sympathy – and gaslighting when you question anything. But, with in-person romance fraud, there’s the added violation of them having touched you. That’s a whole different layer of trauma.”

When Tamsin met Mike, she was nearing 50, and at a low point. Living in south-east England with her teenage daughter and husband of almost 20 years, she had always been the main breadwinner, working in product development. “I was tired, unhappy, feeling unloved, a bit neglected,” she says. “I was in a rut of going to work, going home, doing dinner.” Mike was tall, broad, and 10 years older than her. After swapping numbers, the two began chatting on WhatsApp. “It was constant,” she says. “Question after question. I’ve never known anything like it. We were talking about anything and everything. What we were doing, how we got here, things we liked.” Mike told Tamsin that he was divorced, and, like her, a Christian. (They discussed their favourite hymns.) A month later, they met for dinner in a neighbouring village and more dates followed. Tamsin met Mike’s friends at his local pub. He told her that he owned various rental properties around the world, and was also a partner or investor in a number of businesses. He claimed to be a wealthy man whose money was all tied up. He said that he chose to rent a room with a local family because he wanted company and didn’t like living alone.

Around this time, Mike also revealed that he had a history of cancer – and doctors had recently found a malignant growth in his bowel, the size of a 20 pence piece. Rowe says that this is entirely predictable: “Cancer is used in almost every romance fraud experience.. Either the fraudster has it, or his child, or a close family member.” It makes the fraudster seem vulnerable and, to the victim, worthy of extra care and compassion. If questions arise further down the line, the enormity of a cancer diagnosis is enough to silence them. It also charges the relationship with a new level of urgency.

In the coming weeks, Mike showered Tamsin with affection. “He’d buy me flowers, he messaged constantly with lovely compliments – just wonderful things that made me feel good about myself. He was fun, sociable, full of life. He seemed like the male version of me.” During a stolen weekend in a shepherd’s hut in Port Lympne (Tamsin told her husband she was with her cousin), they planned their future. “We talked about me getting a divorce and us making a life together,” she says. “To me, it was really serious. This is where I was going.” Soon after, though, Mike called her at work with devastating news. His tumour was now the size of a grapefruit. His cancer was terminal. “I had to go outside and cry,” she says. “I was in this crazy, confused world, and I couldn’t tell anyone about it. I was losing my head, struggling to know what to do.” Although she arranged to accompany Mike to his hospital appointments, when the time arrived, he’d always insist on going alone.

Time now seemed precious. They began viewing places to live – huge barn conversions, always with space for Tamsin’s daughter, that Mike said he could pay for. Meanwhile, Tamsin began paying for Mike to stay in hotels. “He was telling me that at home, the hot water wasn’t on and I wasn’t having that,” she says. “He was a mechanic, he did a dirty job. He had cancer. He needed a warm shower, so I insisted.” Finally, Mike claimed that he had bought a local property on family land that he was fully renovating. He didn’t want Tamsin to see it until it was ready and perfect.

It was a fraught time. Mike was losing weight, looking pale, struggling with his mental health and supposedly in and out of hospital. For a brief period, Tamsin even believed that he’d died. Mike’s lawyer and business partner, “Marcus” (who Mike had talked about in the past), messaged her and delivered the news. Tamsin cries as she recalls this. “I was mourning this person, looking up at the stars, talking to a dead man who wasn’t even dead,” she says. After a few days, she was contacted again. Mike had not died after all; he’d been saved in a specialist clinic in Switzerland. It was a turning point. “From then on, I decided that I was not going to lose him. I would not let him out of my sight.”

Tamsin left her marriage, was reunited with Mike and they moved into a hotel, which she paid for. Mike told her he’d bought her a local business of her own - he showed her the building, which was also being renovated – so she resigned from her job. While awaiting all these renovations, they took off on a road trip: Mike told her he wanted her to attend a family reunion up at the very tip of Scotland. To help with cash-flow, Tamsin sold her Audi, exchanging it for a less expensive Mercedes. A few weeks later, she had to sell the Mercedes too, and instead bought an older Passat.

They drove all over the UK – Pembrokeshire, Blackpool, Paisley, Inverness, with Tamsin paying for every meal and every hotel, emptying her savings accounts and using multiple credit cards. She then began messaging her parents and friends, begging for small loans to tide her over – though that had to stop when she also sold her phone. (At that point, she was miles from anyone she knew and cut off completely.)

How could she have been so taken in? “I feared so much that I was going to lose him,” she says. “I’d invested everything – left my family, resigned from my job. I just don’t think my heart could handle any doubts. I was too exhausted to question things, so I think I decided that this had to be it. I love him. He loves me. This is my life now. Trust him.” Denial is a common form of self-protection, says Rowe. “Eventually, most victims know that something is very wrong, but it can take a long time for the heart to catch up with the head. Can you imagine accepting something that will bring the worst pain down on you ever?”

After four months, out of cash, Tamsin and Mike were sleeping in her car. “Each day, we had to choose between paying for food, or a shower, or diesel. I was exhausted. I just wanted it to be over,” she says. She drove back south, dropping Mike in a town centre and telling him that she was going to the doctors to get contraceptives. Instead, she drove to her parents’ home. They had been in touch with the police and informed Tamsin that Mike was wanted for multiple sexual offences. She called the officer in charge of the case, and Mike was arrested that same day.

What did Mike want from her? Tamsin still isn’t sure. “I think it was a final adventure for him, a last horrible hoorah when he knew a case was building against him and he was soon going to be charged,” she says. “I came along and he decided to get as much out of me as he could.” If it was only about money, then why lead her to resign from her job and cut off her income stream? Why invent a cancer? Why make her believe he had died? Tamsin thinks he simply enjoyed the game. Money is only one element of romance fraud, says Rowe. “It’s about power and control, the horrendous emotional manipulation, and the sexual element too – and then the money,” she says. “There is no doubt that perpetrators get an absolute kick out of all of it.”

Two years on, Tamsin is still at the very start of recovery. Staying with her parents, she set about selling all her personal belongings – bags, jewellery, anything branded – to begin paying her debts. She has since found a job, paid back the loans from friends and family and, with the help of Victim Support, agreed a repayment scheme for the £50,000 she owes credit card companies. (Although Victim Support did manage to get one creditor to write off £10,000 of debt, most would not accept that Tamsin was a victim of fraud or economic abuse, since she “benefited” from the expenditure herself.) “I’m ashamed, embarrassed, hurt, humiliated,” she says. “At first, I didn’t want to see anybody. It was just work all the hours God gave me, go home, have dinner, sleep, repeat. I very much cut myself off from the world.” She had stayed in some kind of contact with her daughter through most of this. When she first saw her husband again, his words were, ‘Thank God you’re safe.’ They are slowly rebuilding a relationship, but “it’s tough,” she says.

Tamsin isn’t expecting sympathy. “The crimes he is now in prison for are far worse than anything I’ve been through,” she says. In fact, she is always braced for blame. “That’s what all victims of romance fraud are met with,” says Rowe. “When it finally ends, on top of all the trauma, they’ll be blamed by most people for being so ‘stupid’.”

-

In the UK, victims of in-person romance fraud should report to local police as well as Report Fraud (0300 123 2040). For confidential help and support contact Victim Support (08 08 16 89 111) and Love Said

4 weeks ago

29

4 weeks ago

29