Ten years on from the historic Paris climate summit, which ended with the world’s first and only global agreement to curb greenhouse gas emissions, it is easy to dwell on its failures. But the successes go less remarked.

Renewable energy smashed records last year, growing by 15% and accounting for more than 90% of all new power generation capacity. Investment in clean energy topped $2tn, outstripping that into fossil fuels by two to one.

Electric vehicles now account for about a fifth of new cars sold around the world. Low-carbon power makes up more than half of the generation capacity of China and India, with China’s emissions now flattening, and most developed countries on a downward trend.

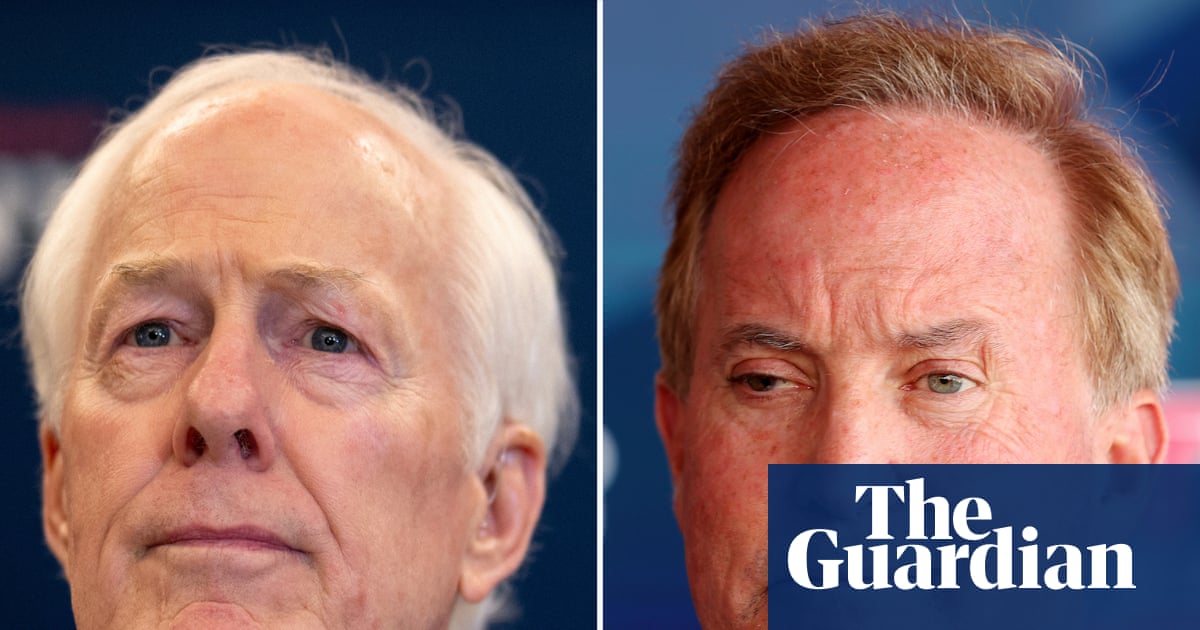

For Laurence Tubiana, a former French diplomat who was one of the main architects of the Paris accord and is now chief executive of the European Climate Foundation, this is a remarkable achievement. “The Paris agreement has set in motion a shift towards clean energy that no country can now ignore,” she said.

Would this have happened without the Paris agreement? Unlikely, according to Bill Hare, chief executive of the Climate Analytics thinktank. He said: “The 1.5C limit [for rising global temperatures] and the net zero goal have reshaped policy, finance, litigation and sectoral rules, helping to rewire how states, markets and institutions work.”

Ed Miliband, the UK energy secretary, said look where temperatures were headed before Paris, if you want to judge the summit’s impact. The planet was on track for more than 4C of heating, a catastrophic increase.

After Paris, that came down to 3C. Then, after Cop26 in Glasgow in 2021, which reaffirmed the 1.5C pledge, carbon-cutting commitments brought the projected temperature rise to about 2.8C. Today, the forecast stands at about 2.5C, if all existing promises are fulfilled.

“We’ve made progress as a world, but we also know that is far short of what we agreed at Paris,” said Miliband. “You’re trying to get 193 countries to agree to these big fundamental questions about the trajectory of their economies, their societies, the way their energy systems work. No wonder it’s difficult.”

Yet the shaky response to the Paris agreement from some key countries in its immediate aftermath has added significantly to the climate crisis we now face, and the failure of rich governments in more recent years to uphold their side of the bargain with the poorer world threatens to implode the global consensus.

The question now is: can countries learn from the mistakes of the past decade, in order to keep the Paris agreement alive in the next?

The history of the last 10 years in climate politics is one of glaring contradictions, forward leaps followed by backsliding, and cooperation attended by fracture. The first blow to the fledgling Paris agreement came within just a year, with the election of Donald Trump as US president in 2016. He vowed to withdraw from the pact, and began the process in 2017.

This year, that pattern looked set to repeat: in January, on re-entry to the White House, Trump began the withdrawal process again, while kicking off damaging global trade turmoil through the imposition of swingeing tariffs.

Though Trump’s first withdrawal did not create the “snowball” effect some had feared – no other functioning country has left since – he may also bear partial responsibility for another blow: after 2016, China vastly speeded up its rate of carbon dioxide output.

When Xi Jinping travelled to Paris in November 2015, and for a short time after, emissions from the world’s second biggest economy looked to be peaking at just under 10bn tonnes per year.

But in 2017, that dream was dashed. Coal-fired power took off again, and China’s carbon output resumed its upward march, at an accelerated pace, reaching 12.3bn tonnes last year.

Beijing economic thinking is opaque and there are still differing conclusions about what caused the spike. Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute, believes the government was seeking to shore up economic growth by traditional means: “It was the real estate market, it was buildings, steel, cement. It’s different now,” he said.

But Paul Bledsoe, a former Clinton White House climate adviser, warns of the damage China’s actions did to arguments for climate action in the US: “In the immediate aftermath of Paris, China began the biggest building spree of coal-fired power plants in history. They went on a coal binge, and the rest of us just had to hope it would subside. It made everyone cynical.”

Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, discerns the hand of Trump in the rise in emissions from 2017. He argued it was “partially a reversal of [China’s] overall economic policy, then it was a response to Trump’s tariffs, then redoubling on using real estate as a growth driver”.

Roughly 90% of the increase in greenhouse gas emissions since the Paris agreement has come from China. And yet those emissions tell only half the story. Last year, China added more renewable energy than the rest of the world combined, and clean energy made up 10% of the country’s GDP, with similar figures likely this year. China’s manufacturing strength has sent the price of solar panels plunging by about 90% in the last decade.

It is true that China may yet return to coal, but Wang Yi, a senior adviser to the Chinese government, said at Cop30 last month that Xi Jinping was committed to clean energy for the long term. “The central government, including President Xi, is very clear to us that we must, in the next five years, speed up the new power system,” Wang said.

If the world should manage to cling to the 1.5C limit – which is still possible, according to Hare, if the current overshoot is swiftly remedied, then China will deserve a large slice of the credit.

And where China leads, India has followed. The country’s carbon emissions outstrip Europe’s, and it could overtake the US in a decade to become the world’s second biggest emitter after China.

But half of India’s installed power generation capacity is now low-carbon, and the country met its target on renewable energy five years ahead of time. Wind and particularly solar are set to grow even faster this year, but coal production has also surged.

Arunabha Ghosh, chief executive of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water thinktank, said the country is headed for a clean future: “India is now planning for a grid that can absorb much larger volumes of renewable energy. This is transformative. All the building blocks are there.”

The Paris agreement, in which countries agreed to limit global temperature rises to “well below 2C” above preindustrial levels while “pursuing efforts” to stay within 1.5C, was possible only because of the determined efforts of a global alliance in which some of the poorest and most vulnerable countries made common cause with some of the richest and most polluting.

The High Ambition Coalition, spearheaded by the charismatic Marshall Islands diplomat Tony de Brum, brought more than 100 countries together and drove the final months of work.

But many observers are worried about a fracture between developed and developing countries that has appeared to widen at recent Cop summits. Poorer countries were shocked by the global north’s tardiness in sharing vaccines during the Covid-19 pandemic, but they supported moves at Cop26 in Glasgow in 2021 to reinforce the 1.5C goal.

They hoped the rich countries would reciprocate the next year with help for the loss and damage fund – money that goes to the rescue and rehabilitation of communities stricken by climate disaster – but only achieved that with a struggle.

Then, last year, at Cop29 in Azerbaijan, rich nations provoked fury from the global south when they refused until the final hours to put numbers on their contribution to the $1.3tn a year promised in climate finance by 2035, and tried to feint at first with a lower sum than the $300bn finally agreed.

Evans Njewa, chair of the UN’s Least Developed Countries grouping, reminds rich countries that providing financial assistance is an obligation, rather than an option. “We expect that these commitments will set into real, sustained financial flows,” he said.

“Climate finance to us is not charity. It is a legal obligation, so it must be mobilised and be provided to us. It is the only means of a global response to this global crisis.”

At the most recent climate summit, poorer countries did achieve the tripling of finance for adaptation, to $120bn a year, though it will not be fully realised until 2035, rather than the 2030 deadline they preferred.

That could go some way to rebuilding trust, but one participant in the talks told the Guardian that poor and vulnerable countries “do not want to be taken for granted”, and would need further evidence of rich countries’ solidarity.

If Paris is to survive, the rich countries will need to do more to fulfil their promises and heal the rift. They will also need to lead on the roadmaps to phase out oil and gas stemming from a voluntary agreement made at Cop30.

That is likely to mean working with petro states – such as the United Arab Emirates, under whose Cop28 presidency in 2023 the promise to “transition away from fossil fuels” was originally made – rather than shunning them.

Meanwhile, the biggest developing economies must show that renewable energy can substitute for fossil fuels, rather than being additional to them, and can bring down carbon rapidly, rather than simply subduing its rate of increase.

All of these efforts will face outright hostility and possibly attempted sabotage by the US.

Though Trump sent no delegation to Cop30, his officials played an extraordinary role at the International Maritime Organisation negotiations on a potential carbon levy in October. Developing country delegates were plagued with intimidatory emails and phone calls from the US state department, threatening visa revocations and economic sanctions. Countries are now braced for what US tactics may come next.

For Tina Stege, climate envoy for the Marshall Islands, today’s changed geopolitics presents the biggest threat to the Paris consensus. “Climate change negotiations do not take place in a vacuum. They reflect the increasingly multipolar world we live in,” she said.

“Unlike some other multilateral processes, though, we continue to make progress against all odds. That this progress is incremental and not in line with needs on the ground is obviously extremely frustrating. [But] we are prepared to continue to work with all partners to secure a viable future for our people.”

For large as well as small countries, she adds, multilateral cooperation on the climate is the best hope, as “We do not have the option to go it alone.”

2 months ago

56

2 months ago

56