Six weeks ago, Alex Winter was on stage at the first night of previews for Waiting for Godot – the latest Broadway revival of Samuel Beckett’s absurdist masterpiece, in which Winter plays the puttering Vladimir to Keanu Reeves’s equally aimless Estragon.

Winter is an old pro at live performance: he spent almost all of his middle and high school years on Broadway, eight shows a week. He and Reeves, his longtime friend and most righteous co-star of the Bill & Ted movies, had the idea for the revival three years ago and have been prepping ever since.

And yet, on stage for the first time since he was a teenager, the 60-year-old actor had a moment of panic. “I was like: ‘Oh, holy shit! What if I’m wrong?” he says, perched on a velvet sofa in a lounge at the theatre, a few hours before he goes on again. “And I’m looking at Keanu, who’s in a similar state of terror. And – well, it would have worried me if either of us were like, ‘whatever.’”

The show, of course, went on. Winter and Reeves, the beloved time-travelling slackers of yore reunited as befuddled buddies in timeless purgatory, are now a third of the way through their 16-week run. Winter looks relaxed, sipping tea, in a blue scarf, at once garrulous and introspective. He’s in favour of people feeling the precipitous fear of creative risk a little more. “One hundred percent. There should be a jumping-out-of-an-airplane [feeling] without, you know, jumping out of an airplane.”

Winter would know. As well as a return to Broadway, this season brings the release of Adulthood, his first film as director in over a decade. (He also appears in the black comedy as a weirdo stoner.) A child actor turned movie star turned director and producer and prolific tech documentarian, Winter’s career has been fitful, searching and unconventional, full of sharp left turns and voracious curiosity. (On Godot, the New Yorker’s Helen Shaw reported, accurately, that Winter’s “palpable intelligence drives the show.”) Returning to Broadway, where he made his debut at age 13, is a bit like closing a loop. “I’ve lived like three lifetimes since then. But now being backstage and doing my warm-ups, being in the wings and seeing the stagehands – it feels like I never left. It’s like a complete time-bend.”

One that is shared with Reeves, the eccentric, thoughtful yin to Winter’s quick and chatty yang, a “lifesaver” with whom Winter most recently appeared on-screen in Bill & Ted Face the Music (2020). “I knew that this was a mammoth undertaking, and the only reason I felt we could pull it off was that it was the two of us together,” he says. Working with Reeves provides “an immediate sense of comfort. I know I can trust him and he can trust me. We genuinely have each other’s backs. There’s no bullshit.”

Reeves and Winter, with ever-precise comic timing and inimitable chemistry, are the leaven in this bleak existentialist affair, lending lines such as “together again at last …” a jolt of sweetness – and indulging in a flourish of air guitar. Indeed, Winter says, performing with Reeves again “is like being in a band.” (The two both play bass.) “It’s this fluid give-and-take. Sometimes I’m cooking and he’s catching up. Sometimes I’m catching up and he’s cooking. Sometimes we’re helping each other out of a hole. Sometimes we’re just on a fucking groove and we look at each other and go: ‘God damn, that was good! Where the fuck did that come from?’”

Vladimir and Estragon, two longtime friends with a vaudeville past, share qualities with the duo – particularly a “questioning of faith and life” – that have drawn them together since their early 20s. “We were both really into literature and drama, but also just like, what the fuck is this world? How do you live in it?” Winter laughs. How do you maintain artistic integrity and have a Hollywood career? How do you keep having fun? And, after the success of Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure in 1989, how do you be famous?

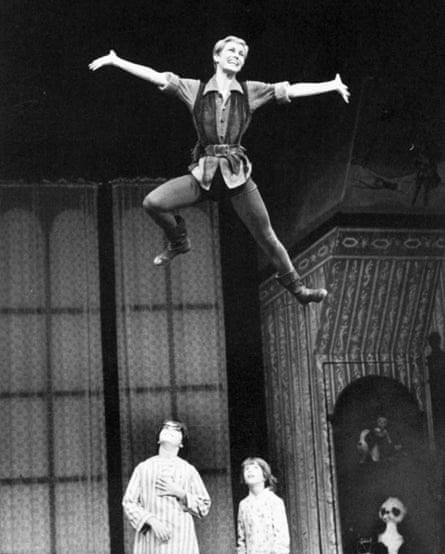

By this point, Winter had already been acting over half his life. Born in England to two modern dancers, he first got on stage at age 10 in St Louis, Missouri; when he, aged 12, and his mother moved to New York following divorce, she got him a children’s talent agent. Within a month, he was on Broadway opposite Yul Brynner in The King and I. He spent most of his high school years in Peter Pan, playing John Darling next to Sandy Duncan.

Here, he developed the trademark discipline of a child actor – a subject he later explored in his 2020 documentary Showbiz Kids – and lasting emotional scars from prolonged sexual abuse by an unnamed adult who, he says, has since died. The “nightmarish” experience, which he did not reveal publicly until 2018, left him with “extreme PTSD” and mental fracturing that, as he told the Guardian in 2020, got “worse and worse and worse.”

He didn’t talk about it and kept working, – first an off-Broadway play, then commercials, then NYU film school, then an audition for Joel Schumacher’s vampire drama The Lost Boys. The director encouraged him to drop out. The part was small, but the movie, released in 1987, “totally changed my life”. A year short of graduation, he moved to LA.

By the time Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey sequel was released in 1991, Winter had already shifted focus, directing music videos and commercials and co-creating the Idiot Box, a late-night sketch series for MTV. In 1993, he co-wrote and co-directed the cult hit Freaked, in which he played a former child star who is kidnapped and turned into a mutant by Randy Quaid. By 26, he was “fried.” Winter dismissed his agents and decamped for New York, then London, where he formed a production company. “I just wanted to get the hell out of the public eye, and just be on the tube, going to my office in Soho and start a family,” he says. He found a therapist, and started confronting the trauma of abuse. He had three children, the youngest of whom is about to graduate high school in LA.

And he began pursuing rangy nonfiction interests as a documentarian – first Napster, the download site that revolutionised the consumption of music; then Bitcoin and the dark web; then the Panama Papers, Blockchain and the iconoclastic musician Frank Zappa. His most recent documentary, 2022’s The YouTube Effect, traced the video sharing platform’s arc from cute novelty to conspiracy theory machine. “My career is where I want it, which is that I have the ability to do whatever interests me the most,” he notes sagely. “But I would not have been OK had I not split.”

Adulthood, which Winter co-produced from a script by Michael MB Galvin, brings some of Winter’s prevailing concerns back into the realm of metaphor: two siblings, manchild Noah (Josh Gad) and strait-laced Megan (Kaya Scodelario), discover a literal skeleton in their parents’ basement, triggering a deadly spiral of bad decisions fuelled by fear of financial and reputational ruin. The film, says Winter, “is at heart about the unrelenting and unspoken impossibility of living in this culture today” and the “fallacy of the middle class” in countries, such as the US and the UK, that are actively hollowing it out.

Winter has never been shy about his political affiliations. Earlier this year, he helped organise anti-Musk Tesla Takedown protests – and is quick to tie the siblings’ absurd hijinks back to the larger US climate. In Adulthood, “stress can subtly shift you into immoral acts, which is very much about the times that we’re in, where people who were Bernie bros suddenly went Maga,” he says. The very online, pathetic Noah draws, in part, on Winter’s experience in the bowels of YouTube. “Having been around so many fanboy-type people because of my work, I feel like I know them very well,” he says. “I don’t have contempt for them, but I do think they need to grow up.”

Winter, long a chronicler of the internet’s maturation, now has his sights trained on AI. “I’ve been thinking about an AI doc for about five years, and it hasn’t been the right time because it’s moving so fast,” he says. During the writers’ and actors’ strikes, held in part over AI protections, Winter acted as an interlocutor of sorts, running Zoom consortiums for guild members with AI technologists, academics, copyright lawyers and patent experts. “Most of the criticism is really fucking dumb,” he says, “like people who are out there saying, ‘I’m a leader in the anti-AI charge, and we have to create this law or that’, and they just have no idea what they’re talking about and none of it is ever going to work.”

He is not anti-regulation, more pro accurate and clear information, and certainly anti-huckster. “There’s a lot of smart people in this space,” with “good morals,” he says. (This does not, he notes, include OpenAI’s Sam Altman.) But “the reality of it is there will be an enormous amount of carnage on the way to things being OK. In every area, from Hollywood to climate to journalism, people are getting fired all over the place. They’re not getting replaced by a robot. They’re just not getting replaced.”

Economic stress, job displacement, the rightward shift toward authoritarianism to solve the problems it can’t and won’t fix – it’s an old cycle, now playing out again, that brings us back to Godot, based in part on Beckett’s experience in the French resistance during the second world war. Winter returns to a question posed by Estragon in act I – “We’ve no rights any more?” – as the duo submit to waiting for no one. Vladimir answers: “We got rid of them.”

“Every night, I say that line to Keanu: ‘We got rid of our rights,’” says Winter ruefully. “We were fucking idiots. We did it again.” And, as ever, the show goes on.

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48