On the surface, Vancouver Whitecaps CEO Axel Schuster’s press conference last week would have felt familiar to almost any North American sports fan. Once again, a team was agitating for more money or a better stadium. Once again, local governments were at least partially to blame.

Some of his comments, though, felt more alien, and raised a question that seemed unfathomable just a couple of months ago: are the Vancouver Whitecaps about to die?

The Whitecaps were among Major League Soccer’s most competitive sides in 2025, eliminating Inter Miami from the Concacaf Champions Cup early in the year and losing to Miami, the eventual champions, in MLS Cup. They feature a global superstar in Thomas Müller and are just weeks away from their home opener. Lingering in the background, though, the club is for sale, with their financial state and their inability to find a new home cited as the primary reasons.

That situation, Schuster revealed last week, has only bleakened.

Schuster said the Whitecaps generate less revenue than any other franchise in the league. Indeed, some reports say that on matchdays, they are entitled to as little as 12% of the take at BC Place, the multipurpose stadium they’ve called home since entering MLS in 2011. The stadium has bona fides, having hosted the 2015 Women’s World Cup final, with two Canada games to come at this summer’s men’s World Cup. However, it’s also very popular. The Whitecaps are one tenant among many, and the terms of their lease have not materially changed in the 15 years they’ve been in operation. Negotiations for better terms with PavCO, the province-owned operators of the stadium, have proved fruitless, said Schuster. The city and Whitecaps have a one-year “memorandum of understanding” to explore other stadium options, but as of now, nothing viable has come of it.

More striking than any of this, though, were Schuster’s comments about the club’s search for new investors. The club was publicly put up for sale in late 2024. Since then, Schuster revealed, “almost 40” groups entered into non-disclosure agreements with the Whitecaps and were given a look at the club’s financial data.

“As of now, at this moment, no one, not one single one, is interested in buying even 1% of this club,” Schuster told reporters, “because all of them think that our setup here and the market and the situation we are in is not something where you can invest in as long as [things don’t change completely].”

It’s a level of transparency that feels uncommon in situations like these, where businesses more often than not strive to present themselves in the rosiest terms possible while they search for a buyer. Schuster’s comments felt at times more like the league, and Whitecaps, are laying the groundwork for a relocation, or even some form of contraction.

A league statement, released concurrently, mirrored much of Schuster’s commentary.

“Operational constraints around scheduling and venue access have intensified in 2026, creating untenable conditions for a major league club, with no clear path forward to resolving these challenges in future years,” the statement read in part. “This is not fair to the club or its fans … meaningful progress is urgently required to establish a sustainable path forward.”

Like any professional sports league in North America, MLS has a history of franchise relocation and contraction. The league eliminated two of its original franchises, the Tampa Bay Mutiny and Miami Fusion, less than a half-decade after its founding. The San Jose Earthquakes moved to Houston in 2005 before restarting in 2008. In 2014, the Chivas USA folded, with MLS eventually selling the franchise rights to the current-day owners of LAFC.

The one case since then was especially fraught: In 2017, MLS very nearly approved the relocation of a league original, the Columbus Crew, before a grassroots effort helped save the team. Anthony Precourt, the Crew’s owner, was tapped to own expansion side Austin FC instead.

MLS is a fundamentally different place than it was in 2011, when the Whitecaps were founded. It is no longer a collection of largely unprofitable clubs who appeal to a small niche of American sports fans. . In 2013, NYC FC entered the league for $100m. San Diego FC, the league’s most recent franchise, paid five times that sum a decade later. Most recently, Sporting Kansas City sold to a new majority owner at a $700m valuation. At this point, it feels more like big business.

After decades of rapid MLS expansion, league commissioner Don Garber has declined, for now, to outline any plans for adding more franchises. With that door theoretically closed, potential MLS markets like Sacramento, or Detroit, or more recently Indianapolis, would probably jump at the opportunity to lure an existing franchise like the Whitecaps, or buy the rights to one from the league.

The Whitecaps are not entirely without value to an investor who wants to keep them local, though. Far from it. For a modern MLS team, they have a strong brand identity, one steeped in a history that dates back to the team’s original incarnation in the 1970s and one that’s still deeply meaningful in-market. They’ve showed ambition at times, as they did with the signing of Müller, and they are well-supported, even during rough patches. Though sometimes lost in the shuffle with their Cascadian neighbors in Seattle and Portland, Vancouver remain an important part of that important trio of rivals.

Yet maybe more than any other club in MLS, the Whitecaps face a laundry list of scheduling challenges, with BC Place frequently booked for other events (the Whitecaps nearly lost hosting rights for a playoff game due to a scheduling conflict with a motocross event at their home stadium last year). Those conflicts will only increase in 2026, when the men’s World Cup visits BC Place. The Whitecaps have their full slate of regular-season matches and will also take part in Concacaf Champions League, Leagues Cup and Canadian Cup play as well.

None of these issues, though, are as insurmountable as the bare fact that the Whitecaps do not own the stadium they call home. This type of arrangement used to be commonplace in MLS but faded with the advent of soccer specific stadiums. Vancouver’s arrangement feels a bit like the one DC United navigated until 2018. Unable to broker a stadium deal with the District of Columbia, United languished at RFK Stadium for years under a lease agreement with the city that gave them little to no matchday revenue outside of ticket sales.

MLS – and DC United – had strong words for the District government, even leveraging nebulous interest from nearby Maryland and Virginia. United eventually got their downtown stadium, but have struggled mightily to claw their way back to relevance after a decade or so out of the spotlight.

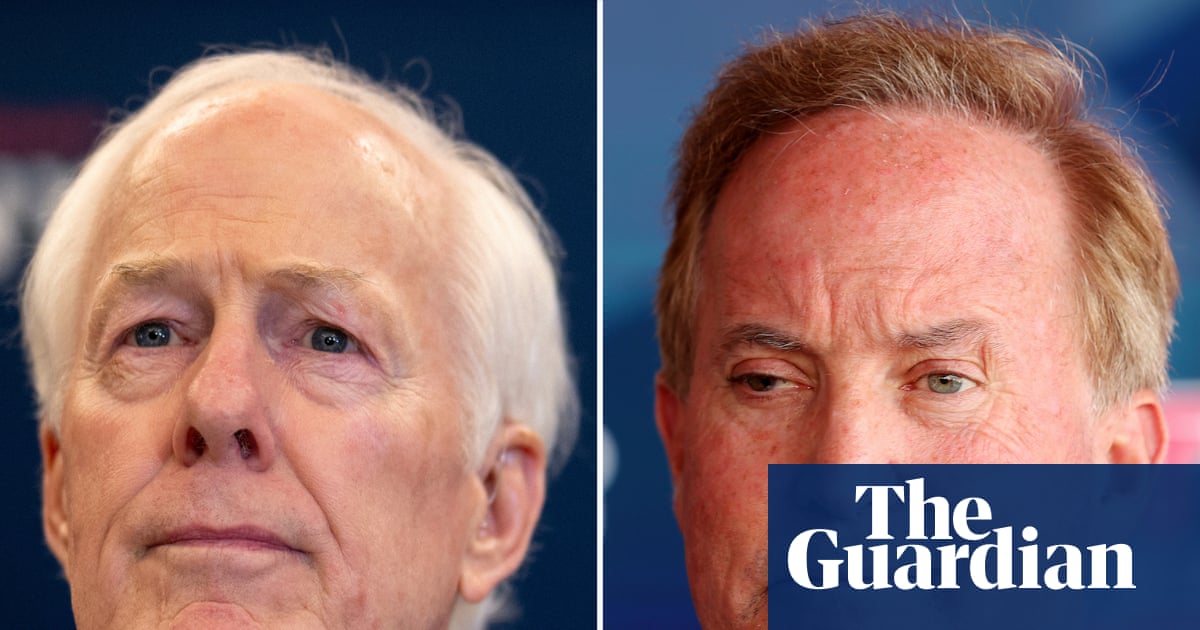

In Vancouver, opinions on the club’s ownership group – majority owner Greg Kerfoot and a handful of smaller investors, which includes former NBA legend Steve Nash – skews negative, with more than a handful of fans placing the blame for the club’s financial state and lack of a stadium plan squarely on their shoulders.

It’s perhaps the most frustrating thing about North American sports: a strong brand identity, strong local support and even results on the field are often not enough without the backing of a billionaire. That holds particularly true in MLS, where some teams still operate at a loss and franchise valuations, even while they skyrocket, sometimes don’t justify absorbing decades of losses.

Many of the club’s longtime fans will be understandably hopeful that the Whitecaps can find a way to stay in Vancouver. Based on the comments of the club’s CEO – and the league – it feels more likely that the end of the road may be drawing near.

4 weeks ago

29

4 weeks ago

29