It is just before dawn, the December temperature a couple of degrees above freezing; time for troop rotations to start across Ukraine’s 750 mile front.

A crew of four from Da Vinci Wolves battalion are loading up into an M113 armoured personnel carrier at a secret location ready to be driven out to a safe point. From there they will walk to their position and remain on the front for 10 or 12 days.

There is little room in the back, but spirits are high, perhaps with nervous excitement. How are they, all good? “Wonderful, wonderful,” is the affirmative reply.

-

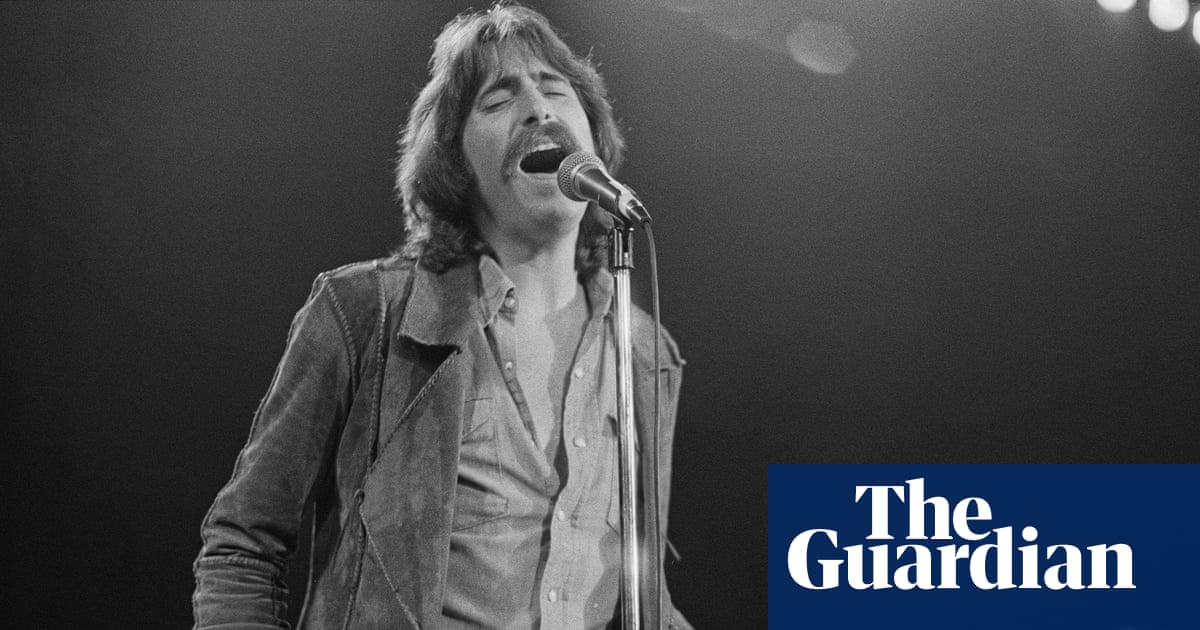

Drone pilots of Da Vinci Wolves battalion prepare to return to the frontline.

At this time, the only light comes from inside the armoured vehicle, though the goal is not for the soldiers to enter their positions at night.

Once it was safest to deploy only in the dark, but now the growing number of Russian drones with thermal cameras, easily able to pick out a person from above, mean that it is probably safer to move during “grey weather” – the gloomy and sometimes wet or foggy winter mornings on the Novopavlisky axis, a stretch of Ukraine’s eastern front south-west of Pokrovsk.

By the time the Da Vinci crew get to their drop-off point, there will be a degree of daylight, giving them their best chance of getting to their dugout or basement from where they will operate.

-

Troops reach the rotation point as daylight begins to break. From there, they will walk to their dugout and remain there for 10 to 12 days.

It is early enough in December to ask if the outgoing crew, whose ages range from 20 to 32, will be back before Christmas. “We’ll be back before Christmas, yes, but then there’ll be another rotation. So we’ll be out again at Christmas. The work never stops,” says 30-year-old Dark, using his military call-sign.

A shortage of personnel and, in particular, the danger of drones above has meant that the time spent by soldiers on the frontline is becoming longer and longer. A little over a year ago, the Guardian spent time with a drone crew from the Khyzhak brigade, who would swap in and out of their positions every three days.

A year on, that sounds quaint. Once the troops are clamped inside the armoured vehicle, it is time to wait for the return of those coming off duty. They are the survivors of the moment. Due first is an infantry squad, who have spent 38 days on the front, to be followed by a returning drone crew, back after two weeks.

-

Solodenkyi and Pavuk, infantry soldiers, and the power banks they were using during their 38 days in position.

-

Oleksandr, an infantry soldier with Da Vinci Wolves battalion, pleased to be smoking what he says are proper cigarettes.

Two hours later, it is daylight, just about. For a time there is silence, and a pensive wait, though when the tracked armoured personnel carrier is close, the engine noise is unmistakable. When it stops, three soldiers emerge from two doors at the back, stretching as they come out of their metal cocoon.

The vehicle is in turn surrounded by an exoskeleton of netting – a final, hopeful barrier to prevent a drone detonating dangerously next to the armour plating itself.

The faces of soldiers coming from a position are unmistakable, with open eyes and dirty skin. On their helmets is roughly spun blue tape, intended to mark them out as Ukrainians and so avoid friendly fire. But for now they are safe.

Oleksandr, 37, is the most talkative of the group, pleased to be smoking what he says are proper cigarettes, complaining that the cigarettes dropped in by drone were an inferior brand. He says he is most looking forward to “a shower and rest – we will have as much rest as they will give us”.

Solodenkyi’s call sign means sweet, though the 42-year-old’s strong features suggest a more serious demeanour. He appears exhausted, but also in the first moment of freedom from the front, relieved. The walk to their early morning pick-up point began at 10pm the previous night.

Infantry and drone crews have opposite tasks. A drone squad is constantly busy, either on reconnaissance or attack, searching for Russian infiltrators, theoretically working in pairs but sometimes all hours if their zone is under threat.

The job of infantry is simply to hold a position, to hide and avoid being spotted by drones. In the 38 days, Oleksandr says they had “no contact” with any Russians – success not just in terms of their survival but in terms of holding their point on the frontline that runs from Kharkiv region in the north to the Dnipro river in the west.

-

The faces of soldiers coming from a position are unmistakable, with eyes wide open and dirty skin.

Next up is a returning drone crew, their stint two weeks long. The receiving team has been told one is injured and a medical team are on standby, ready to take the wounded soldier to a nearby stabilisation point for treatment.

But it turns out that the soldier in question – call sign Estonian, 34 – is only lightly hurt. He limps out of the armoured vehicle that has brought them back at a reasonable speed, keen to get in a car with his buddies and recover at his own pace.

A Russian drone struck when Estonian was going towards his position – “it was 700 metres away”, he says before heading off. Meanwhile, the waiting medics congratulate themselves for being able to make somebody better without having to do anything.

-

Jesus, the drone pilot, after 14 days i on the frontline.

The drone crew, operators of Chinese-made Mavic quadcopters, is a little less keen to stop and linger, with the exception of Jesus, 22, who stands to be photographed, inhaling deeply on what appears to be the best cigarette of his life.

There is little to no respite from the cramped confines of a bunker – they should venture out only for drone-dropped food and other supplies – and it is critical they are not spotted as they are an important target for the Russians. Now, he can feel the cool air and relax.

Was it busy? “There was enough work,” Jesus replies, smiling between drags, not offering many words. How does it feel to be back? “I feel amazing,” he replies, full of life on the greyest of mornings. How long is your break? “Also two weeks”.

1 month ago

37

1 month ago

37