Set pieces, eh, those brief but frequent interludes that sporadically pockmark our weekly sacrament, filling our heads with daydreams and fantasies of intricately worked ruses or 30-yard thunderbolts. Quite often the unintentional birth child of an ugly hacked clearance or theatrical swan dive, they ordinarily result in nothing more than a rudimentary blemish upon hallowed turf canvas but, sometimes, just sometimes, we are treated to strokes of genius that become as entrenched in the memory as is the Lord’s Prayer.

When asked to provide a dose of professional insight detailing the fastidious workings that go into each and every single stoppage in play, it got me to thinking: have we lost an element of ingenuity in the pursuit of perfection? My dad has always warned me against the pitfalls of starting a game slowly so, with that pearl of wisdom well heeded, I’ll get things under way with a bang, a no-nonsense punt into touch from the very first whistle, the sort that’s recently stormed back into fashion within the upper echelons of the English game, as world-renowned coaches such as Pep Guardiola and Mikel Arteta do their damndest at reinventing a century-old wheel.

Let me espouse my disdain for football’s latest fad: the role of the set-piece coach. Usually spotted emerging from the shadows of luxuriously appointed benches (you don’t get splinters any more you know, trust me I’ve been there) during free-kicks, penalties, corners, goal kicks or the keeper scratching his arse, you may often mistake these pensive-faced experts for the first-team manager.

They celebrate a successfully defended corner (a wayward delivery headed wholeheartedly clear) like a last-minute winner and a “well-worked” goal like the birth of a new Messiah, while in the process frantically searching for the “gaffer” and any hint of his approval.

It’s a tough school. One errant move on their human chess board and a bitter chastising awaits. Woe betide any player with a smidgen of imagination or rebellious streak. If predetermined plans fail to be followed to the nth degree, then a good old-fashioned tongue lashing awaits.

I’m well aware there is plenty at stake in the modern game and ample stockpiles of cash specifically designated to vanity projects such as these, but we mustn’t lose sight of what our game is at its core: an entertainment sport contested by highly skilled individuals, not a virtual simulation marshalled by dubiously qualified, tracksuited orchestrators. In a hypothetical Room 101 type scenario, I’d be banishing this new-fangled obsession with a skyward bound kick from the hands, the type of which hazy old replays of The Big Match joyously provide every Saturday morning.

With that small gripe off my chest, let’s take a closer look at what occurs on the training pitch at the smaller clubs who don’t have the luxury/misfortune of employing a set-play maestro.

At almost every club I’ve played at, the role of dead-ball organiser is usually designated to a member of the coaching staff who will prepare an elaborate playbook of various manoeuvres. Strangely enough, this niche and somewhat unenviable task has fallen increasingly under the remit of the goalkeeping coach, which is quite concerning when you consider their well-earned reputation for daftness.

You may have noticed them donning a battered old pair of Copas (flip chart or iPad in hand) while bombarding a late substitute with a never ending list of hastily ordained roles – “you’re front post for defensive corners”, “block their No 29 if we take a short one”, “if they get one within shooting range, charge out of the wall like Zaire in ‘74” – just what you want to be hearing as you prepare for a token gesture two minute pipe-opener with your team 3-0 down.

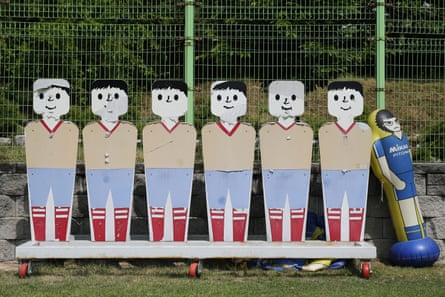

Each and every eventuality has been meticulously rehearsed before matchday. Usually this will occur on a Friday after the standard fare of pre-game five a-side. Come wind, rain or shine, or a bemusing mixture of all three seeing as though we are talking about Scotland, half an hour will be dedicated to a walk through of the set plays. The starting XI will approach this ritual with a smidgen more enthusiasm than those subs/unselected squad members who must role-play the forthcoming opposition.

Most of the work is centred around the countering of potential threats, with the aforementioned substitutes masquerading as the attacking team in order to iron out any potential issues. This will often result in a 5ft 5in pre-pubescent full-back posing as a grizzled 6ft-wide aerial threat, the result being a general feeling of apathy towards the whole charade.

Attacking options, while undoubtedly well planned, are mainly focused on the creation of space from the utilisation of blocking tactics. Executed correctly these obstructive methods can prove deadly but patterns seldom unfold in the exact same manner during competitive action. Free-kicks are barely practised at all, on the subject of which I’ll introduce another pet hate of mine – the sole use of one free-kick or corner taker.

Quite often the only time you’ll notice these “dead-ball experts” is when they are sauntering over in the direction of the corner flag with one or both arms aloft like they are relaying football’s very own version of morse code. Careers can be sustained on the back of this coveted title, so it’s little wonder, then, that there are often a swarm of pretenders who are eager to throw their hat in the ring.

I’d categorise very few of these as true “experts”, but with an average of around five corners per team/per game this season in the SPFL, there’s ample opportunity to register some assists over the course of a 38-game campaign and in the process thrust yourself into the statistically crazed spotlight of the onlooking scouting number crunchers.

Any free-kick within 30 yards is now overwhelmingly likely to be hit at goal regardless of the probability of a successful outcome. Players chiefly concerned with creating their own highlights reel rarely think outside the box and will only deviate from the norm under strict instruction from the autocratic leadership. Perhaps this reflects the game in a broader sense, with managers feeling the weight of expectation, their default setting soon becomes one of negativity and an overbearing discouragement of individual thought soon pervades.

On the eve of penning this piece, a glimpse of set-piece salvation did appear from northern Italy. Famous as the setting for Romeo and Juliet, Verona has long held an association with William Shakespeare, but even the bard himself would have struggled to find the words to do Inter’s opening goal justice. A first-half corner presented Inter with an opportunity to lump the ball goalwards, but they had other ideas. With all the nonchalance of a Milanese fashion designer sparking up an expertly rolled Golden Virginia, Hakan Calhanoglu clipped a 30-yard ball deliciously to the onrushing boot of Piotr Zielinski, who proceeded to use his instep to produce a volley of prodigious proportions.

I was pleasantly surprised, if somewhat annoyed, to discover that this majestic piece of art was the brainchild of, yes you guessed it, the Inter set-piece coach. Perhaps we are entering the Renaissance Era for set pieces? A brave new dawn of experimental innovations that will stave off the drudgery of 15 wrestling combatants crammed into the six-yard box. If that is to be the case, then we will need a handful of mavericks to throw themselves into the breach and cast off the shackles of pitchside oppression. To be or not to be, that is the question.

This article was written by Liam Grimshaw, a professional footballer with a passion for the pen, and appeared first in the new issue of Nutmeg.

2 months ago

41

2 months ago

41