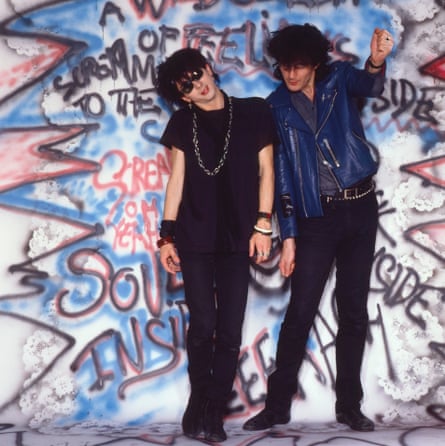

By common consent, Soft Cell’s first Top of the Pops appearance, on 13 August 1981, ranks among the show’s most striking performances. It was impactful enough to send their single Tainted Love first into the Top Ten, then to No 1 – it ultimately became the second biggest-selling single of the year – and to provoke a number of complaints. The latter were caused by the duo’s frontman, Marc Almond, clad in eyeliner and jewellery, delivering his vocal with a weird combination of intense passion, high camp and occasional knowing looks to camera: he was clearly a gay man, but a gay man who declined to conform to the pantomime stereotype that still prevailed on British TV, a decision that first upset his own record company boss – who collared Almond backstage and protested “you’ve got to butch it up a bit!” – then apparently caused the BBC’s switchboards to light up.

Almond was such an arresting presence that it was easy to overlook the other guy on stage, moustachioed, mute and virtually motionless behind his keyboard. But, as his bandmate was given to pointing out, overlooking Dave Ball was a terrible misjudgement. “He really was a psycho,” Almond later recalled. “There would be times when he’d leap from behind the keyboards if someone was threatening me on stage, and he’d punch someone in the front row.”

Moreover, Ball was every bit as integral to Soft Cell’s success as Almond. He had grown up in Blackpool, one of northern soul’s hotspots, and was largely responsible for the music’s presence in Soft Cell’s oeuvre: they covered not just Gloria Jones’s warp-speed stomper Tainted Love, but Judy Street’s What and Franki Valli’s The Night, Northern dancefloor favourites all. It was Ball who’d come up with their version of Tainted Love’s hook, by percussively emphasising the first two notes of the song’s bassline on his synth: doink-doink! It was Ball’s childhood love of John Barry soundtracks that gave Soft Cell’s greatest single, the quite extraordinarily spiteful ballad Say Hello, Wave Goodbye – with its cinematic lushness and Ball’s Korg-bass synth – that became the signature of their early sound (you can hear it used to impressively filthy effect on Tainted Love’s follow-up, the Top 5 hit Bedsitter). And if he looked less of an obvious threat to the heteronormative mores of middle England than his bandmate, Ball was equally committed to the idea that Soft Cell should be a pop band that could, in Almond’s words, “provoke people, shock them, wake them up, be subversive”. His own tastes in electronic music ran less to synth-pop than the confrontational racket made by Suicide and Throbbing Gristle.

Ball and Almond’s own desire for confrontation made them stand out, even in the anything-goes climate of post-punk pop, as demonstrated by the tabloid furore caused by the video for Sex Dwarf, a track from their debut album Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret, and the fact that their debut album had a track called Sex Dwarf on it in the first place.

It made for a succession of startling releases, but after their initial brace of hits, it also proved their commercial downfall: anything-goes climate or not, trailing their second album with two singles that respectively concern themselves with a horribly dysfunctional family (Where the Heart Is) and amphetamine-fuelled compulsive sexual behaviour (the John Rechy-inspired Numbers) proved a little too much for the British record-buying public. By the time of their third album, 1984’s extraordinary This Last Night in Sodom, it was hard to avoid the feeling Ball and Almond were going out of their way to destroy whatever remained of their pop success. Produced by Ball and recorded in mono “just to be bloody-minded”, it sounded claustrophobic, chaotic and viscerally thrilling: on one track, the clanking, improvised, completely atonal Mr Self Destruct, Ball really let his love of industrial music run riot. Its lead single Soul Inside was accompanied by a video of the duo smashing up their gold and platinum discs. They broke up shortly after its release.

On Ball’s subsequent solo album, In Strict Tempo, he ventured deeper into the musical leftfield: equally influenced by dance, classical and industrial music, it featured vocals by Genesis P-Orridge and Gavin Friday of the Virgin Prunes, while its cover star was Geoff Rushton, better known as John Balance of Coil. But after its release, he worked mainly as a producer and remixer. He kept up his association with Genesis P-Orridge, contributing to Jack the Tab and Tekno Acid Beat, two 1988 Psychic TV projects that billed themselves as acid house albums, despite sounding substantially less like acid house than Soft Cell’s first single Memorabilia which, with its relentless four to the floor kick drum and trebly chattering synth, weirdly presaged the music sweeping Britain during the Second Summer of Love in 1988.

In fact, Ball was ahead of the curve when it came to acid house in more ways than one. Introduced to the then-legal drug MDMA in New York during the making of Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret, the duo let it consume their remix album Non Stop Ecstatic Dancing. The clue was in the title, not that anyone in the UK at the time would have known what ecstasy was, or indeed what the rap on a new version of Memorabilia was driving at: “We take a pill and shut our eyes and let our love materialise / I don’t mean love on a chocolate box, I mean a love that really rocks.”

In 1989, he formed the Grid with another Psychic TV alumnus, Richard Norris. In a curious echo of Soft Cell’s success with Tainted Love, they scored a huge hit with a track that wasn’t fully representative of what they were about. A commercial house tune driven by a banjo sample and recorded, at least in part, with the intention of irritating dance purists, Swamp Thing was released in 1994 – the same year the duo produced another huge house hit, Billie Ray Martin’s Your Loving Arms – but its perky, radio-friendly tone was some distance from the more esoteric aspects of the Grid’s oeuvre. They had previously collaborated with Timothy Leary and Sun Ra and Roxy Music’s Andy MacKay; the more characteristic tracks on the album from which Swamp Thing was taken, Evolver, heavily featured the treated guitar of Robert Fripp; it might be more fitting if they were remembered for 1990’s sublime Balearic classic Floatation, best heard in Norris and Andy Weatherall’s collaborative Subsonic Grid Mix.

The Grid never split up – they released an entire collaborative album with Fripp in 2021 – but by the early 00s, Ball and Almond, who had intermittently worked together in the 90s, had reconvened Soft Cell. Their initial reformation, which produced 2002’s Cruelty Without Beauty album, quickly floundered after a disastrous American tour. They decided to finish things properly with a one-off 2018 farewell show at London’s O2 Arena, but ended up going on further tours and made a new album, Happiness Not Included. You could understand why their plans changed: the O2 show was rapturously received, a little chaotic and a potent reminder that Soft Cell were a pop duo like no other. Watching Almond leading the audience in a sing-along to Sex Dwarf, or Ball strafing 1983’s Meet Murder My Angel with howling noise from a modular synthesiser, it was hard not to boggle at the idea that this was a band who had ever graced the stage of Top of the Pops or the cover of Smash Hits.

But they had, and you could never quite forget about it, because of the degree of influence their career exerted. They were the first, but certainly not the last British synth-pop duo to marry emotive vocals with icy electronics: Andy Bell of Erasure claimed they “never would have existed” had Soft Cell not existed first. At one extreme, Ball’s intro to Tainted Love has been sampled on hits by Rihanna, Pink and Flo-Rida. At the other, Trent Reznor was so inspired by what he called the “beautiful, heartbreaking, frustrating, messy, combustible” sound of The Art of Falling Apart and This Last Night in Sodom that he borrowed the title of the latter’s opening track for the first track of Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral: Mr Self Destruct.

Being the musical link between Rihanna and Nine Inch Nails is no mean feat, but Dave Ball was not a man much given to blowing his own trumpet: “I just lurked in the background,” he once shrugged. In response, Marc Almond reiterated that overlooking his bandmate was a terrible misjudgement. “Soft Cell,” he told one interviewer firmly, “was more Dave than me”.

3 months ago

80

3 months ago

80