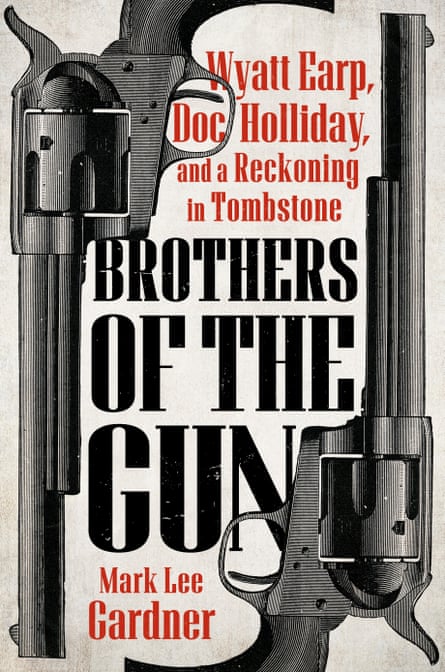

There’s a famous line from a John Ford western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Mark Lee Gardner is a leading historian of the old west whose new book, Brothers of the Gun: Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, and a Reckoning in Tombstone, concerns two major figures in such history. He doesn’t like Ford’s line.

“Every historian uses it, they just beat it to death,” Gardner says cheerfully, by video from Bozeman, Montana.

“And it’s really not true. I wrote a narrative. I want people to be immersed in the time, but I just get so tired of that line. The legend is legend. It never becomes fact. People can repeat the legend but it doesn’t make it fact. It’s just a catchy thing that people have caught on to for decades now. And you’ll notice that I did not use it. I referred to it, but I did not use it.”

Brothers of the Gun is scholarly, engaging, the story of two unlikely but lasting friends, Earp the complicated but upstanding lawman, Holliday the reckless gambler, stricken by tuberculosis.

In Tombstone, Arizona, on 26 October 1881, Earp and Holliday were involved in a shootout that came to be known as the Gunfight at the OK Corral. With Earp’s brothers, the pair confronted the Cowboys, gang members wanted for robbery and rustling. In less than a minute, three Cowboys were dead and Holliday was wounded, as were Virgil and Morgan Earp.

It was one of countless frontier scraps between lawmen and outlaws and yet it entered legend, not least thanks to classic movies including My Darling Clementine, made by Ford in 1946 and starring Henry Fonda as Earp and Victor Mature as Holliday, and Gunfight at the OK Corral, directed by John Sturges in 1957, Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas in the leading roles.

“A lot of what we know about it is verifiable,” Gardner said of the actual fight and sequels, including killings on both sides. “But I always go back to one of the best quotes, and it’s a very simple quote. Addie Borland, who is the dressmaker across the street who witnessed the fight. People were asking for details, and she goes: ‘I don’t know. All was confusion.’

“Even the people there had different stories. I cite often the testimony from what we call the Spicer hearing, and it’s also confusing. You’ve got people that are friends of the Cowboys, so they’re actually lying, and every account is slightly different. It’s rare when somebody agrees on anything. And so I think of Borland’s quote, ‘All was confusion.’ Even the people involved were confused. So it’s really hard to get at it, and it happened in 30 seconds.

“And here’s the hilarious part. I just crack up every time I think of this. You wouldn’t believe how many books have all these massive diagrams of the gunfight. They’ll show each stage. You know, ‘Doc was standing here, Wyatt was over here, and here’s their movement, from Allen Street,’ all the way, they’re tracing with dotted lines. And then they got diagrams where people were, you know, for that 30 seconds … People are so fixated. They want to see ‘exactly what happened’. Well, I’m sorry. I mean, I think I know, pretty close, but I can’t give you a frame-by-frame every second of what’s going on, because even those guys, their stories kind of differ.”

This is America. Stories have always been hard currency. Wyatt Earp lived into the Hollywood age, dying in 1929, aged 80, after plenty of fights over his story, who got to tell it and how. First depicted on a silent movie screen in 1923, then the subject of those two great mid-century westerns, in relatively recent years he’s been played by Kurt Russell (Tombstone, Val Kilmer as Holliday, 1993) and Kevin Costner (Wyatt Earp, with Dennis Quaid, 1994). On the small screen, Wyatt and Morgan Earp appeared in the great HBO series Deadwood, bit parts based on their brief stay in the gold rush town.

Gardner drills through such myth-making to find the men beneath. His books cover the span of the old west. A devotee since childhood, as an adult he first wrote “the definitive study of wagons on the Santa Fe Trail, and in fact the only study on those wagons”. He has since written about Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett, Jesse James, Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, and, most recently, The Earth Is All That Lasts, an award-winning story of “Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and the Last Stand of the Great Sioux Nation”. His next book will turn back to James, the Missouri outlaw famously played by Brad Pitt, and his time as a civil war bushwhacker.

Gardner refuses to romanticize such figures. Earp and Holliday spent time on either side of the law, in a world of violence and greed.

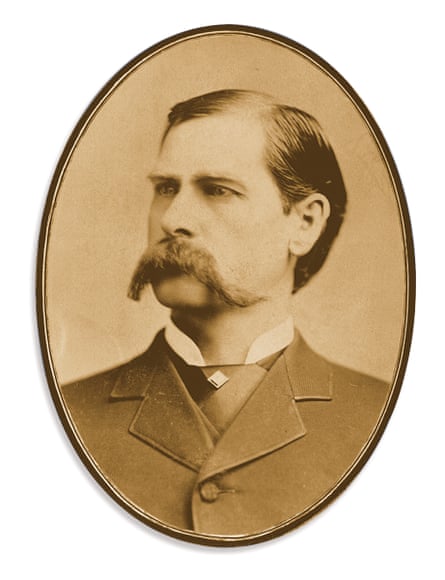

Born in Monmouth, Illinois, in 1848, Earp was too young to fight in the civil war, though he tried to do so. When he was 20, “he became a constable in Lamar, Missouri, this little, tiny town, with no police academy or training. And mistakes were made. Wyatt has a tragedy in his life with the death of his wife” – Urilla Sutherland, of typhoid in 1870 – after which, as constable, Earp kept for himself tax money he collected.

“We don’t know why he kept it,” Gardner says. “He runs, and ends up in Oklahoma. He’s arrested for stealing a horse, and then he’s in Illinois, and he’s running a brothel. I mean, he is literally a pimp. His wife is a prostitute, or his common-law wife, significant other, whatever you call it. He finally heads back west, and he ends up in Wichita, Kansas, and he tries to help the law officer there. There’s a horrible killing, and he impresses the chief of police, and he gets a job. And he excels in that.

“Now, this is the irony: Wyatt Earp is a policeman in Wichita, his wife is working in a brothel, and so is his brother’s wife, but he’s an outstanding police officer. Everybody says so. The newspapers, you read the quotes. They’re always praising him in the paper. There’s one instance where he arrests a drunk and the drunk has $500 on him. Any other officer might have pocketed that money and said he didn’t know what the drunk was talking about. But no, Earp holds the money for the drunk and gives it back when he releases him from jail. The same thing happened in Dodge City.

“He was praised over and over again as a law officer, and later, when Wyatt’s in the [Spicer] hearing to decide whether he’s going to face a trial for murder after the OK Corral, he gets these letters from Wichita and Dodge City, signed by all these citizens, and they praise him to the stars.”

Brothers of the Gun illustrates this fascinating aspect of the old west: friction between law and lawlessness, authorities trying to exert control over newly forming societies, or those societies attempting to rule themselves. The amount of bureaucracy that follows a gunfight – hearings, affidavits, orders for compensation – might be surprising, at least to a reader raised on Clint Eastwood movies, men with no names brooding in vast and terrible lands.

Furthermore, as Gardner shows, Earp and Holliday were as entangled in hard politics as any prominent American from the dawn of the nation to now. Earp was a Republican. Tombstone sheriff Johnny Behan was a Democrat, a rival for influence and office.

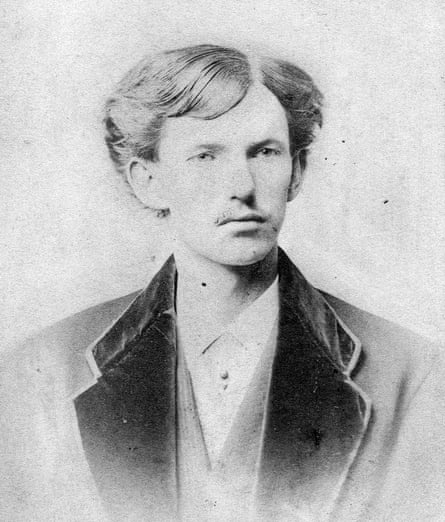

Gardner’s main characters were very different men. Holliday – born in Griffin, Georgia, in 1851, a dentist, hence “Doc” – was dissipated but not in general a thief.

“Wyatt, you know, at least attempted to be something different than he was as a youth,” Gardner says. “He’s trying to better himself. And in Tombstone, he builds a house, he’s doing all the things that are right … I’m kind of sympathetic.

“Now, Doc Holliday, as Wyatt said, he was kind of his own worst enemy. I don’t know if I buy into this fatalism thing” – part of the enduring myth, Holliday’s fatal sentence with tuberculosis supposed to have fueled a reckless streak. “There are instances where he didn’t want to die … But unlike Wyatt, he doesn’t buy a house. You don’t see these signs that he’s going to settle down. Doc just moves from one gambling place, one boomtown, to the next, and he never really changes. And part of that’s his addiction to gambling. Part of that is tuberculosis, dealing with that and self-medicating, whether it’s with alcohol or later laudanum. He doesn’t seem to have this ambition Wyatt does.

“Wyatt is ambitious. He wants to be somebody, and he sees these different steps: deputy sheriff, but he wants to be county sheriff. He’s trying to better himself. And I just don’t see that with Doc Holliday. He just kind of stays the same throughout.”

-

Brothers of the Gun is out now

2 months ago

38

2 months ago

38