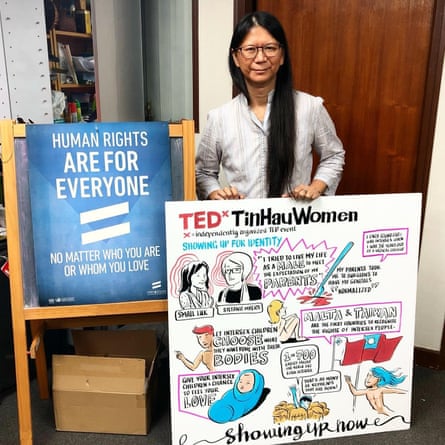

Small Luk was initially “so happy” to be offered genital reconstruction surgery, aged eight. Doctors had told her she was a boy, but that she had an illness, which was why she couldn’t urinate standing up. “They told me this is a problem,” the 60-year-old from Hong Kong says. “And that in the future, you cannot marry, you cannot have a baby, so you need to have surgeries.”

Having been bullied at school for her ambiguous gender presentation, she found the idea that she could be “modified back to normal” a compelling one. But it wasn’t as simple as the doctors made out: Luk had an undeveloped uterus and vagina in her body as well as underdeveloped male genitals.

More than 20 operations later, after surgeons had failed to lengthen her urethra, Luk, by then 13, refused further treatment. During that period “I felt so sad and lonely” she says, and came close to killing herself on two occasions. Of the handful of children whose genitals were operated on at the same Hong Kong hospital in the 1970s , Luk was the only survivor. She found out later that “most of them had [died by] suicide”.

It wasn’t until she was 36, after years of “performing as a man”, that she found out that she has partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (PAIS). Essentially, that meant that although she had the XY chromosomes characteristic of a male, her body didn’t fully respond to testosterone, and would never look fully “masculine”. After doctors advised her that keeping her male genitalia would greatly increase her risk of cancer, Luk agreed to have surgery to remove them and started living legally as a woman. Now, alongside her work as a doctor of Chinese medicine, she is an ardent activist for intersex rights across the globe – calling for an end to genital reconstruction surgeries on children before they are old enough to consent themselves. “I really don’t want them to experience the same suffering,” she says.

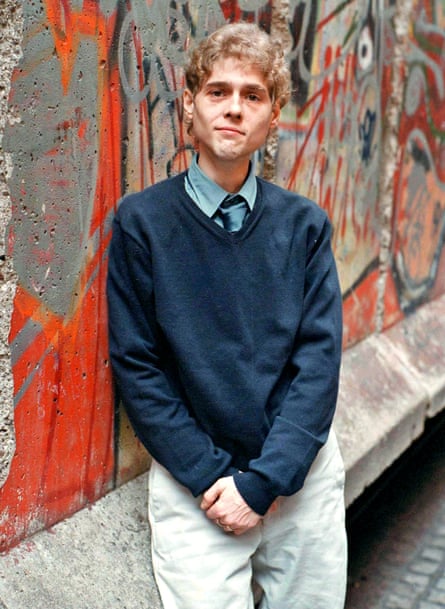

That same plea is echoed in The Secret of Me, a new documentary by British film-maker Grace Hughes-Hallett, which follows the life of Jim Ambrose, who was born in Louisiana in 1976. Like Luk, Ambrose had genitals that, as he puts it in the film, “fall outside of an arbitrary acceptable norm”. Doctors decided to operate on him as an infant, removing his testes and constructing a vagina. His parents were then advised to raise him as a daughter, and keep quiet about what had happened. He was told that he would need to take hormones when he was a teenager, and had further surgery to make his sexual organs appear more “female” as a young adult. But explanations were few and far between, and it was only when Ambrose sought out intersex groups that he was able to fully understand what had happened to him.

The course of action that his parents had been advised to follow brought Ambrose a great deal of misery – he never felt like a girl growing up, and it was a massive blow to learn that such huge decisions had been taken about his body before he could have a say in them. As an adult, having become involved in intersex activism, he stopped taking oestrogen. This had dangerous consequences – because his testes had been removed, his body was unable to produce sex hormones, and he developed osteopenia – a precursor to osteoporosis. A doctor told him he had to either go back on oestrogen or start taking testosterone, and he went for the latter, not out of any great desire to be a man but because he was “pretty into having a functioning skeleton”. Testosterone felt a much better fit than oestrogen, so he switched to using a male name and pronouns, and now lives happily as a man – although it is clear from the documentary that he is still profoundly affected by what he went through.

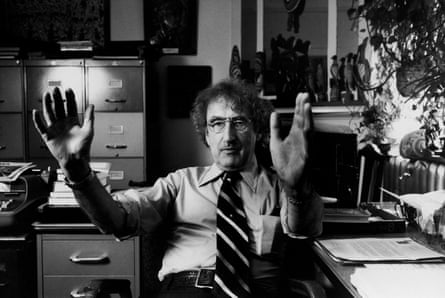

The Secret of Me draws a direct link between the harmful way Ambrose was treated and the work of psychologist John Money, whose theories about gender informed medical guidance about children born with atypical genitalia. In the 1960s, Money studied a pair of Canadian twin boys, originally called Bruce and Brian Reimer. Bruce was left without a penis after a botched circumcision, and the academic encouraged the boys’ parents to raise him as a girl, Brenda. Money studied both children as they grew, with his research claiming the experiment was a total success. Brenda, according to him, was a stereotypical and happy little girl, showing that a child’s gender could be moulded by the adults raising them.

In fact, there were clear signs that Brenda was never happy as a girl, which Money simply left out of his papers. As an adult, he began living as a man, changing his name again, this time to David. The brothers were left traumatised by Money’s research (which involved having them inspect each other’s genitals as children and “rehearse” sexual acts) and their story has an incredibly sad end – both Brian and David killed themselves in their 30s. Money’s work was eventually debunked – but its impact on medical treatment for children born with ambiguous genitalia was felt for years. Richard Carter, the surgeon who operated on Ambrose as a baby, appears in The Secret of Me, and apologises to his former patient. He says when he was tasked with treating Ambrose, he “went back to [his] textbooks” – which featured Money’s work.

Shocking as this all now seems, Money’s offer of a straightforward “fix” to non-stereotypically sexed babies clearly had an appeal, and perhaps still does: we live in a world in which many parents want to know whether to put their newborn in a blue or a pink hat, and gender reconstruction surgery for babies born with differences in sex development (DSD) is still legal in most countries, including the UK and the US.

That doesn’t mean things haven’t improved – an NHS paediatric doctor, who wishes to remain anonymous, says in the UK at least, “It’s a very well run service now.” Any surgeries on children with DSD take place at a “highly specialised centre”, he says, and cases are presented to a panel led by a paediatric endocrinologist – a doctor who has been trained to diagnose and treat children with hormone-related disorders.

A psychologist would also be involved in making the treatment plan, and the team would “absolutely” err on the side of not performing surgery – and certainly wouldn’t perform surgery just to make a child’s genitals look more stereotypically male or female. That kind of intervention would only take place once a child has been through puberty, he says, and surgery performed before that would have to be because, for example, a child would otherwise be incontinent, or at risk of cancer. “Clearly, some of the DSD management is around the parents and their expectations as well,” he adds. “Ultimately, this is a decision often taken and pushed for by the parents.”

He believes that “saying no children with disordered sexual development should have surgery as children is actually quite harmful”, partly because of the range of conditions that fall under the intersex or DSD umbrellas – and the range of treatments those conditions require. Depending on which conditions “count” as intersex (some people would say that someone with polycystic ovary syndrome could consider themselves intersex, for example) as much as 1.7% of the global population could fall within the category – a proportion akin to people with red hair. On the more conservative end, estimates have been as low as 0.018%. If a child is deemed to need genital surgery, “if you do it earlier, they don’t know what’s happened,” the doctor says, and there are likely to be “better outcomes” in terms of healing.

That may be true, says Mitchell Travis, associate professor of law and social justice at the University of Leeds, but is ensuring that a child heals better and forgets the pain of the surgery more important than waiting for them to be old enough to give their own informed consent? He thinks “waiting, seeing what happens is the best thing to do,” in order to avoid situations like the ones Luk and Ambrose experienced.

There are mixed opinions about when someone should be deemed old enough to make a decision about surgery themselves – Luk suggests 14 might be a good age, whereas Travis thinks in the UK the principle of “Gillick competence” – which means the courts could consider a younger child mature enough to consent to their own treatment – could be applied.

Holly Greenberry-Pullen, 47, a Lib Dem councillor and the only openly intersex candidate in the 2024 general election, points out that the information that someone is given to guide their decision about surgery is just as important as their age. Because of what her genitals looked like as a baby, she was raised as a boy until she went through puberty, when “it became really clearly obvious that my body was absolutely intersex”. She agreed to a number of surgeries as a teenager and young adult, but does not believe she was able to give “fully informed consent,” because the doctors misdiagnosed her. “I went through some absolutely horrific mutilating surgeries” that “left me absolutely physically damaged in a way that I thought was irreparable,” she says.

In 2011 Greenberry-Pullen helped to found the charity Intersex UK. “If there is no life-saving, essential medical urgency and factual diagnosis that means you have to perform an irreversible surgery, then you don’t do it,” she says. “Wes Streeting [the health secretary] needs to invite me and colleagues into Westminster to sit around the table and to talk about human rights and the right to bodily autonomy and medical policy on how intersex bodies are treated.”

But is legislation in the UK necessary now, given that procedures have been updated since Greenberry-Pullen was a teenager? Travis admits that in the countries that have implemented a ban on non-essential genital reconstruction surgeries on children, such as Kenya and Germany, there has been “mixed success”. For instance, in 2015 Malta was the first country to put this kind of prohibition in place, but a 2020 study the academic co-wrote found the country had never been doing the surgeries in the first place – they had been outsourced to the UK as part of the countries’ bilateral health agreement. So while it is technically illegal for such surgeries to take place, “it’s kind of up in the air” whether they can still happen via the UK, Travis says.

The lack of a good model for this kind of ban is one argument against advocating for it – but the point of legislating wouldn’t just be to prevent damaging surgery, Travis explains, but also to give people a legal route to fight back if they have already experienced surgery they feel was unnecessary and damaging. Currently in the UK, “you couldn’t bring a negligence case or something like that,” because performing surgery on children with DSD is “within the professional guidelines,” he says.

“The irony is that where a trans kid can’t access a hormone blocker, an intersex child is operated on,” Greenberry-Pullen says – she is of the school of thought that fighting for better rights for transgender people goes hand in hand with the lobby for intersex rights. There is a range of views on this point within the intersex community: some are happy to be included under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella, while others are not – and some prefer not to use the term “intersex” at all, opting for DSD instead.

For Greenberry-Pullen, intersex and trans identities are distinct but have some shared challenges, and she thinks things such as the supreme court ruling of what a woman is hurt intersex people as well as the trans community. “It is completely flawed because they’ve only used binary sex as a model and a premise to base everything else upon,” she says. The Tory government “erased all the work” Intersex UK had done in terms of progressing intersex rights, she believes, and the charity is “on a slow burn at the moment”. US charity InterACT, too, has “pulled back away from legislative fronts”, executive director Erika Lorshbough says, given the current administration’s rollback on policies designed to protect trans and intersex people.

Neither charity is expecting to get anywhere with surgery-banning legislation any time soon – though for another UK charity, dsdfamilies, getting this kind of legislation is not necessarily the answer. Such laws can simply be “a way of saying that something is being done without actually spending money,” says dsdfamilies trustee, Jo Williams .“What is really lacking is the psychological and family support for parents and families who are trying to raise children,” she says. In her view, it is “definitely” better to assign a child with a DSD male or female at birth – but to tell parents to “keep an open mind about it”. If, as some intersex activists would prefer, children were raised without a binary gender, or encouraged to come to their own conclusions when they are ready, they might feel more isolated. “Are you going to want to have the only child who is being raised as intersex in your entire school or even the whole town?” she says.

Which gets at what seems to be the crux of the whole issue: there is no blueprint for how to live in a body that is not easily definable as male or female, so people are encouraged to pick one side or the other – or have it picked for them by their parents or a doctor – which doesn’t always work. Even for Luk, who has chosen female as the best option for her legal gender, it still doesn’t sit quite right. She accepts being perceived as a woman, because otherwise “I’d need to spend so much time explaining what’s meant,” she says. But “I don’t really feel I’m a female. I’m intersex.”

The Secret of Me is being screened at Everyman at the Whiteley, London, on 12 November, and will be on Channel 4 in 2026

2 months ago

45

2 months ago

45