Jennifer Chaparro Pernet cannot remember the exact moment she became aware of a commotion outside the prison. But she recalls feeling a ripple of excitement when she heard people shouting, and then a guard calling her name. By 6pm she was walking out of El Buen Pastor women’s prison in Bogotá, a small bag of clothes in her hand, to a cacophony of banging, cheering and stomping as her fellow prisoners celebrated her release. She was four years into a 12-year sentence.

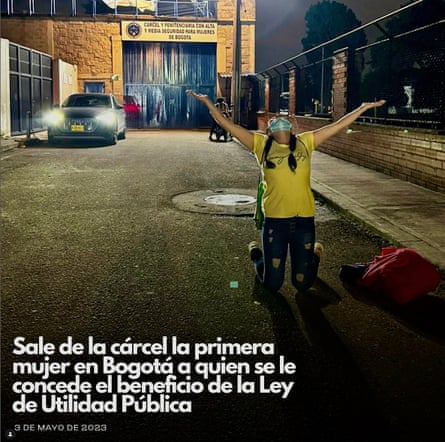

It was 4 May 2024, and Chaparro Pernet, 36, was the first woman to be released under Colombia’s 2023 Public Utility law, which allows first-time female offenders who are heads of households with caring responsibilities to apply to serve their remaining sentence in the community.

She was stunned by the turn of events. After passing through the prison gates she fell to her knees before tearfully answering questions from the TV reporters who had gathered to record the moment.

“I was overwhelmed, I could hardly believe it. I thought, ‘God exists, it’s a miracle’,” she says.

Although she applied to the scheme as soon as it became law, her application was rejected three times, and while she never gave up hope, she was wary of being too optimistic. Instead, she focused on maintaining a good record.

Her release was greeted with joy and incredulity by her cellmates. “Whenever someone left jail it was always a feeling of happiness. But we didn’t know [Jennifer] was leaving [under the new law]. Many didn’t believe it could be true,” says Sandra Julieth Cantor, who was released from El Buen Pastor 10 months later on 8 March 2025.

Chaparro Pernet does not want to go into detail about why she ended up in prison but says she started stealing at 15 when she became a single mother, and at 27 she was forced to join a gang. Her affiliation with gang members meant she received a harsher sentence – 18 years, reduced to 12 on appeal.

More than 6,000 women are in prison in Colombia, about half of whom are serving sentences for drug offences. The Public Utility law recognises that many of these women come from poverty and turned to the drugs trade in desperation, often as a means to feed their families. Lack of money also means they cannot afford a good defence lawyer, or in some cases any lawyer.

Cantor, a mother of one, served five years of a 10-year sentence for drug smuggling before her release. “I was carrying 6,055 grams of cocaine (13lbs). I know the exact figure – because it was the 55 that pushed me into a higher sentence bracket. [If I had been carrying] 6,000 or less would have been four years.”

After becoming a single mother at 20, she turned to prostitution as a source of income. When that work dried up during the pandemic, a boyfriend introduced her to drug smuggling. She always planned to stop when she had saved enough money to go back to college but he offered her one more job – the one that led to her arrest.

In prison Cantor shared a cell, with two concrete bunk beds and a toilet in the middle, with five other women, two of whom slept on the floor. “My apartment was one of the prettiest cells – I called it my apartment – I had sown nice curtains, but it couldn’t detract from the lack of privacy and terrible food. I left with gastro [issues], the meat is rotten.”

For both women, the strongest motivation was not escaping the grim conditions but a desperation to be reunited with their children and families. Chaparro Pernet cries as she tells the Guardian how she lost contact with her two daughters while she was inside. Cantor’s family persuaded her not to tell her nine-year-old daughter why she had suddenly disappeared from her life – a lie, she says, that nearly drove the girl to take her own life.

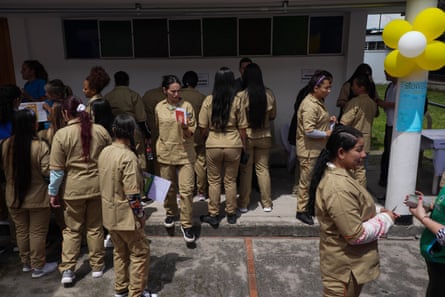

Since the law came into force, 216 women have been released, the most recent figures show. The freed women are not tagged but have to complete a minimum of 20 hours a week of voluntary service and report to a judge regularly.

Hailed as a pioneering model for reform when it came into force in 2024, nearly two years on, campaigners say the law has not had the impact they had hoped for. “We were expecting at least half of the 6,000 women in prison would be released within two years, so [just over] 200 is very disappointing,” says Isabel Pereira, drug policy coordinator at Dejusticia, a Colombian thinktank. “There is no official data on how many women have applied [for release] but from what we’ve heard informally many are being denied.”

Part of the problem is the wide variety in how the law is interpreted, with some judges applying very strict criteria and others being more lenient. Pereira says lack of awareness among the female prison population is another challenge.

But Claudia Cardona, a former prisoner who runs the campaign group Mujeres Libres and was involved in the development of the law from the beginning, says even slow progress feels like a win. “From our experience as women who were incarcerated we believe that, although the number of women who have benefited is still small, every woman who is now free and with her family matters. For us … it is significant.”

Both Pereira and Cardona agree that one major flaw is the lack of integrated support on release, and want to see better coordination between the ministries of justice, education, work and health to ensure women have the conditions to not just survive but thrive outside prison.

“Today, women face enormous barriers: society judges and stigmatises them, there are no real job opportunities, no financial inclusion, family ties are broken, there is no solid foundation for women’s economic autonomy, and they continue to experience various forms of violence, including institutional violence,” says Cardona. “Without public policy for women released from prison, it is very difficult to move forward and ensure that women can maintain their freedom and rebuild their lives with dignity.”

When Chaparro Pernet was freed she found a job in a restaurant through a scheme introduced under the Second Chances law in 2022, but it was short term. Nearly two years after leaving El Buen Pastor she still does not have a secure job. It would be easy to lose faith were it not for the support she gets through the Accíon Interna Foundation, a non-profit set up by Johana Bahamón, to rehabilitate former prisoners through training and psychosocial and legal support.

Bahamón was a successful actor but a visit to a women’s prison in 2012 became a turning point. “I asked the director to give me a tour – where they sleep, what they eat, what they do – and I thought, you can be deprived of your freedom but you don’t have to be deprived of your dignity, and that is my motivation to keep working.”

Bahamón started with what she knew: acting. She began a drama workshop, inviting prisoners to audition for a part in a play. “We rehearsed for three months and then presented the House of Bernarda Alba by [Federico] García Lorca. When I watched these 12 women performing – they had a glow in their eyes, with hope – I thought, this is what I want to do. And that was it.” She thought the prisoners deserved a wider audience and spent eight months persuading the Ministry of Justice to allow prisoners leave to perform to an outside audience. Now six prisons put on a play every other year, with the winning production being invited to perform at the Ibero-American theatre festival in Bogotá.

In 2016, Bahamón helped establish Colombia’s first prison restaurant open to the public in Santiago prison, Cartagena. One woman who left prison in 2019 after completing her sentence told Bahamón she wished she could go back to prison because at least she had work there, inspiring Bahamón to set up a “second chances” programme in the same year. She also campaigned for the Second Chances law that came into force three years later. Over the years, the organisation has helped thousands of former prisoners, including dozens of women released under the Public Utility law, but stigma facing the formerly incarcerated means huge barriers still exist.

Chaparro Pernet and Cantor continue to attend courses at the foundation in the hope of finding work. Cantor hopes to become a hairdresser. Chaparro Pernet says she just wants a good job “to provide a stable income for my family”.

“These are very strong women who are really fighting to leave the past behind,” says the foundation’s communications director, Camilo Higuera, himself a former prisoner. “They are the epitome of why you need to give someone a second chance – they only think about their family. We admire them.”

1 month ago

33

1 month ago

33