A few years ago, I bought my mother a notebook for her recipes. It was a weighty, leather-bound affair that could act as a vault for all the vivid stews, slow-cooked beans and many other family specialities – the secrets of which existed only in her head. Although the gift has basically been a failure (bar a lengthy WhatsApp message detailing her complex jollof rice methodology, she still has an allergy to writing down cooking techniques or quantities), I think the impulse behind it is sound and highly relatable. Family recipes are a form of time travel. An act of cultural preservation that connects us deeply to people we may not have met and places we may not have visited.

Those realities shine through in this week’s gathered compendium of heirloom recipes submitted by readers. Baked beans given a Gujarati twist. An Atlantic-hopping riff on spinach and feta pie. A billowing yorkshire pudding with sticky bramley apples in its base. All of these preparations, particularly when a recipe for anything is a mere tap away, point to the power of human connection and the ingenuity of domestic chefs. And perhaps the best thing about ancestral culinary approaches is that they can be passed from one clan to another, living on even as they are adapted and evolve.

So enjoy these evocative accounts, cook these dishes (untouched and untested by the Feast team, in the spirit of keeping them in their original form) and, perhaps, let another delicious new tradition into your own family’s ever-shifting culinary story.

‘I hope one day my son will pass down the recipe to his children’

“My favourite recipe is Bapa’s beans – tinned baked beans turned into a delicious Indian curry,” says Sonia, 40, from Manchester. “My grandfather, who passed away 20 years ago, showed me this recipe. We used to have it with traditional Gujarati rotli (small, thin chapati). I make this for my husband and our two boys, and serve it with hot buttery sourdough to turn it into an Indian version of beans on toast.”

For Sonia, the dish helps her remember her grandad and “hold on as much as [she] can” to her Indian identity. “When my brother and I were little, we spent a lot of time with our Indian grandparents (who came to the UK from Gujarat, India) in their small, cold, terraced house in Bradford.

Ba [grandma] did all of the cooking; fresh vegetarian curries with rotis and rice every day, served with pickles, poppadoms and all the trimmings. She was, and still is, a brilliant cook. When it was my Bapa’s [grandad’s] turn to take over the kitchen and feed us kids, he made Bapa’s beans with rotis – from the freezer, that Ba had made for emergencies like this.

“Requiring minimal prep and with minimal room for failure, it’s easy to see why this was the only thing that Ba ever showed him how to make. My grandparents could make a meal out of anything. Even though there was not much money, there was always a feast, and whoever was there would be included.

“Before leaving home for university in Manchester, I asked them to show me how to make Bapa’s beans and I’ve made them almost every month since,” Sonia says.

She adds: “I can feel Bapa sitting with my family every time we eat them. I’ll be teaching my 15-year-old son how to make Bapa’s beans before he leaves home … I hope that one day he will pass this recipe down to his own children.” Sonia, 40, Manchester

Bapa’s beans

2 tbsp cooking oil

1 brown onion, diced

1/2 tsp of asafoetida

5 cloves of garlic, thinly sliced

1/2 tsp mustard seeds

2 400g tins of baked beans

1 tsp carom seeds

1/2 tsp chilli powder

2 heaped tsp ground cumin

2 heaped tsp turmeric powder

1 heaped tsp coriander powder

A handful of fresh chopped coriander

Salt

Heat the oil in a pan and add the mustard seeds. Cover with a lid and wait until the seeds stop popping. Add the asafoetida and let it sizzle for a few seconds.

Add the diced onion and salt, and gently fry on a medium heat. Once golden, add garlic slices and fry for a few more minutes. Add the rest of the spices, apart from the carom seeds, and fry for 2 minutes.

Pour in two cans of baked beans and stir through until well mixed. Add carom seeds and simmer for 15 mins.

Finally, stir through the fresh coriander. Serve with hot, buttery sourdough toast.

‘This recipe is my connection to three women I never knew’

Grant lives in Canada but grew up eating this Christmas pudding with white sauce, a dish that links him to his grandmas from Scotland and Yorkshire. It is his most cherished recipe, he says.

“Made with chopped bread, not flour, [the Christmas pudding recipe] travelled from Scotland to Canada with my grandmother, written in her own hand on a small sheet of paper, and we’ve made it every year for as long as I can remember.”

Every November, his parents would bring out “the special pudding bowl passed down from my father’s mum”, he recalls. “That bowl, worn smooth with decades of use, was the signal that the season had begun. As a child, the sight of it meant Christmas was on its way; as an adult, it became a special memory [that takes me] back to the quiet joy of watching my mum and dad work together in the kitchen, creating that dark, moist, fragrant pudding.

“When I eventually set out on my own, I asked my mum for the recipe. She produced the original page, still in my grandmother’s graceful cursive. The ink had begun to soften and feather, the paper fragile and browned at the edges – a patina of time, travel, and countless baking spills. I remember holding it like a relic.

“It’s more than a delicious, spiced pudding. It’s a piece of our history – a recipe barely changed since it crossed the ocean, passed from a woman I never had the chance to meet, now living on in my own home each winter.

“When I asked about how the white sauce came to be, my mum said that my grandmother (from Yorkshire) found it in a 1940s women’s magazine. Food is a connecting mechanism, and this is a connection to three women I never knew: my grandma and great-grandma from Scotland, and my grandma from Yorkshire.” Grant Whitehead, 57, Canada

Grandma’s Christmas pudding

Dry ingredients

1 cup flour

1 tsp baking powder

¼ tsp baking soda

¼ tsp salt

½ tsp cinnamon

¼ tsp nutmeg, freshly ground

¼ tsp cloves

¼ tsp allspice

1 cup soft brown bread, cut into cubes

½ cup brown sugar

Fruit mix

1 cup seedless raisins

1 cup currants

1 cup dates, chopped

½ cup peel

½ cup chopped walnuts (optional)

Wet ingredients

½ cup butter, softened

2 eggs

⅓ cup molasses

1 cup milk

¼ tsp vanilla

Grease and flour a heatproof bowl. (A covered pudding bowl is best, but any decorative, tall ceramic bowl is fine.) Combine all the dry ingredients in a large bowl and stir to mix. Dust the fruit mixture well with flour, then add it to the dry ingredients. Fold to combine.

In a separate bowl, cream the butter until softened. Add the eggs and lightly beat them into the butter. Add the molasses and milk, stirring thoroughly to combine. The molasses doesn’t always bind easily with the butter, so this may take up to a minute.

Add this wet mixture to the fruit and dry ingredients. Fold gently until thoroughly combined.

Spoon the batter evenly into the greased pudding bowl. The batter is thick, so gently pat it down. Gently whack the bowl on a surface to remove any air bubbles. Cover with a lid, or if no lid is available, cover with foil and tie securely with string.

Put a plate in the bottom of a pot and then place the pudding bowl in the pot. Fill the pot with water so it comes halfway up the pudding bowl. Cover the pot with a lid, bring to a boil, then reduce heat to medium-low to create a steam bath. You do not want a rolling boil that will disturb the bowl. Small puddings should be steamed for one to two hours, check at one hour; large puddings can take up to three hours.

Grandma Whitehead’s white sauce

2 cups milk (at least 2%)

1/2 cup white sugar

1 tbsp of butter

2 tbsp cornstarch

1 tsp vanilla

Bring a large pot of water to a boil. Then place a heatproof bowl on top, ensuring the water is not touching the bowl. In this bowl, combine the sugar and cornstarch, mix together. Once mixed, push it to one side of the bowl.

Add the butter to the opposite side from the sugar/cornstarch mixture. Once the butter begins to melt, mix it gently together with the sugar/cornstarch mixture. This will prevent any lumping. Add vanilla and stir. Gradually add all of the milk, stirring well each time the milk is added. Do not mix rapidly as this will create froth; something you don’t want.

Keep stirring continuously, adjusting heat if water boils over. Keep cooking until the cornstarch has created desired consistency. (I like a custard-like consistency so it’s thick but able to put over pudding.) Can be made two days before [making the pudding] and kept in fridge. To reheat, place it in a heatproof bowl over simmering water to prevent burning. Warm up gently and pour over servings.

‘It is my family’s story on a plate’

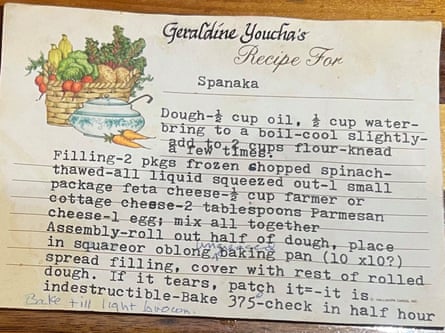

For Zack, spinaka – a spinach and feta pie – tells the story of resilience. “The dish came to New York with my great-grandmother, Frieda, from Turkey,” says Zack, 27, who works in music at a non-profit. “Frieda was orphaned at a young age in a small Ottoman village (what is now Turkey). Her siblings left for the Americas, leaving Frieda, eight, to fend for herself.

“Spinaka was something she made to get through those tough years. It nourished her as she mended soldiers’ clothing, scraping together enough money to make the journey to New York. When she arrived in the city, life didn’t get much easier. She married and had six kids, but two died. Then the Great Depression hit, and she had to work, feed the family, and take night classes so she could learn to read and write. Again, spinaka kept everyone going: the ingredients were affordable, it was packed full of nutrients, and it could be made in large quantities.

“I’ve never seen anyone else do it with the dough that my family uses. While typically made with layered phyllo dough, we make spinaka with a more crude ‘peasant dough’. You boil water and olive oil, then add flour, knead briefly, and roll out … When I make spinaka, I season the dough and add sumac to the filling. Once baked, you always serve each slice with fresh lemon juice and cracked black pepper on top.”

Spinaka remains a mainstay of family gatherings. “I learned the recipe from my grandmother, who learned it from her mother-in-law,” says Zack. “It’s the dish that made me discover my love of cooking. It sounds funny to say, but spinaka is at the core of my family. Even when we spend a holiday or birthday fighting with each other, we still sit around the table and savour this delicious pie together. It is always on the table.”

Zack adds: “Later, Frieda would make the dish for her grandchildren and great-grandchildren at her apartment in Coney Island … Spinaka was no longer a necessity for Frieda’s survival, but she kept making it. There is something very powerful about that.

“I’m humbled by that fact every time I eat the dish, and I’m proud to have this culinary connection to my roots. Spinaka is my family story on a plate.” Zack, 27, New York

‘It’s everything a stew should be’

Desanka Bajic always looked forward to making the Serbian stew passed down by her father, who was from the former Yugoslavia. “[It’s] called boranja, which I recently found out from my Kosovan neighbours means beans,” says Desanka, 69, who lives in London. “It is a lamb-and-green-bean stew in a tomato-based sauce, with loads of sweet paprika and potatoes. My dad showed my mum, who would cook it in the winter, just as I do now. It’s everything a stew should be: rich and full of flavour, substantial, smells divine when cooking, due to the paprika. It cooks for four hours and tastes better the second day.”

Desanka grew up in England in the 1950s and 60s and remembers the food of her childhood being pretty boring. “The highlight, apart from sweets and chocolate, was fish and chips from the local chippy. But having a Yugoslav father brought food into our house that other English working-class kids did not have. And our mum, who was from Lancashire, learned to make a few things such as goulash and boranja. These were so much tastier than anything else we used to eat.

“Food was definitely a focal point at Slava [an annual day when a family celebrates their patron saint] every January. We held an open house all day, and all of my dad’s friends would visit. The smell of salami, peppers and cigarette and cigar smoke would permeate our small terrace … As a young child, it was the highlight of my year – plus, [I would get] a day off school. So food was a highlight, and the smell of boranja cooking is still something I love.” Desanka Bajic, 69, London

Boranja

1kg leg or shoulder of lamb, diced and tossed in seasoned flour

2 large brown onions, sliced

400g chopped tomatoes

Tomato puree

2 litres (approximately) lamb stock

4-5 garlic cloves, crushed

1kg large potatoes, peeled and quartered

At least 500g runner beans, thinly sliced; ideally fresh, but frozen will do

3 large tbsp sweet Hungarian paprika

Salt and pepper

Make the stew in the usual way, making sure to toss the meat in flour to thicken the gravy. Hold back the potatoes and green beans for the first two hours. Then add them [to the pot], cooking the stew on a low heat and stirring regularly for four hours. Make sure it doesn’t stick to the bottom of the pan. It tastes better on the second day and freezes well.

‘I wanted a taste of my grandmother’s cooking when I was away from home’

The name for the delicious cake that Ben, a 72-year-old economist from Canada, has enjoyed over the years came about after he pined for a taste of home. “I was at Cardiff University in 1978 and was missing something,” he says. “I rang up my grandmother in Canada (which cost a fortune in those days) and asked her to send me the honey cake recipe so I could have a special taste of her cooking with me.

“She was a bit taken aback, and told me she did not have anything written down but promised to send me something in the post. The recipe was in her lovely handwriting, [and] at the end, she wrote ‘Good Luck’ – perhaps she was dubious as to whether I would succeed. In any case, everyone in the family now refers to this cake as ‘Good Luck’ honey cake.

“My grandmother had learned the recipe from her mum, my great-grandmother, who no doubt learned it from her mum. My grandmother always made it in a round pan with a hole in the middle, [and] served it for Jewish holidays, especially the Jewish new year and at breakfast after the Yom Kippur fast. I make it whenever I want to celebrate her and have a sweet to offer guests.” Ben, 72, Canada

‘Preserving knowledge and skills’ in salami and celeriac toasts

For Justine, cooking the recipes of her grandmother has been an act of archiving, ensuring that they are accessible for generations to come. “In the midst of one of the lockdowns in 2020, I borrowed my grandmother’s recipe notebook. I digitised it and shared it with the whole family,” says 34-year-old Justine, who is based in Cologne, Germany.

“This recipe notebook is full of hundreds of traditional Belgian and French recipes,” says Justine, whose grandmother trained as a “professional home cook” in the 1950s in Etterbeek. “However, the recipe that stands out is her famous Toasts au céleri et au salami (salami and celeriac toasts), a family favourite that has always brought us together for the apéritif.

“The instructions are simple: mix the celeriac and mayonnaise before piling up the salami, tomatoes, egg and parsley on to white-bread canapés. As these toasts are often eaten at Christmas, when it’s cold outside, you can add a thin layer of butter to the toast. You could also add a turn of the black-pepper mill if you feel fancy.”

Her grandmother was pleased to know that Justine was digitising these recipes, viewing “it as a way of connecting when she was no longer there”. And that is just what has happened, she says. “My paternal grandmother passed away last October. Although she was 88, we were still surprised. As my aunt put it, we all thought she was immortal, given that her own father died three months short of his 100th birthday.”

Justine’s family became interested in her little recipe notebook when her grandmother died, because, she surmises: “I think they realised what they could lose if they were not paying attention.”

“Now that this is published,” Justine says, “she might become somewhat immortal after all.” Justine, 34, Cologne, Germany

‘My brother and I like to make our mother’s recipes’

Although Susan left home unable to cook, today she enjoys recreating some of her late mother’s dishes. One that gets an annual outing is “apple batter”. “It’s yorkshire pudding with Bramley apples in it, topped with hot golden syrup. It’s warm and comforting, and melts on the tongue,” says Susan, 66, who lives in Kent.

“My mother wouldn’t let us in the kitchen while she was cooking, so me, my brother and my sister all left home unable to cook,” she explains. “When I moved to London in 1978, I survived on Smash [instant mashed potatoes], which I thought was wildly exciting, and melon. Then I met my husband in my 20s, and he showed me how to cook, and now I love cooking.”

The family is not entirely sure where the recipe came from, but think it could have been from “a women’s magazine”, as their mother “barely had any recipe books”.

“It is like a very large yorkshire pudding, which you make from scratch because the apples have to go in as you put the batter into the hot oil,” says Susan. Once it comes out of the oven, “still fizzing”, you pour over the syrup and serve with double cream. “I probably make this once a year or when I am cooking for the whole family,” she says.

“We made sure, before my mother died three years ago, that we asked her for the basic family recipes, so they didn’t go with her. Now, my brother and I make her recipes – it is tremendously important to our father that we keep cooking the food she cooked for him. We hope it offers him comfort and reassurance.” Susan Searle, 66, Kent

Additional reporting by Saranka Maheswaran

Family ties

From the hoppel poppel – a kind of bubble and squeak – Yotam Ottolenghi’s mother used to make, to Welsh cakes passed on to Anna Jones, and an intriguing South African shepherd’s pie Thomasina Miers got from her mischievous Nanna Mimi, here are a few top cooks on the hand-me-down recipes they re-create in the kitchen.

-

From coconut curry to hoppel poppel: Yotam Ottolenghi’s family recipes

-

A South African shepherd’s pie: Thomasina Miers’ family recipe for bobotie

-

Liam Charles’s recipe for coconut bread pudding – direct from his nan’s kitchen

-

Bitter-sweet memories: Rachel Roddy’s recipe for marmalade cake

-

‘A favourite Sunday treat of my childhood’: how to make Felicity Cloake’s gooey treacle tart

1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31