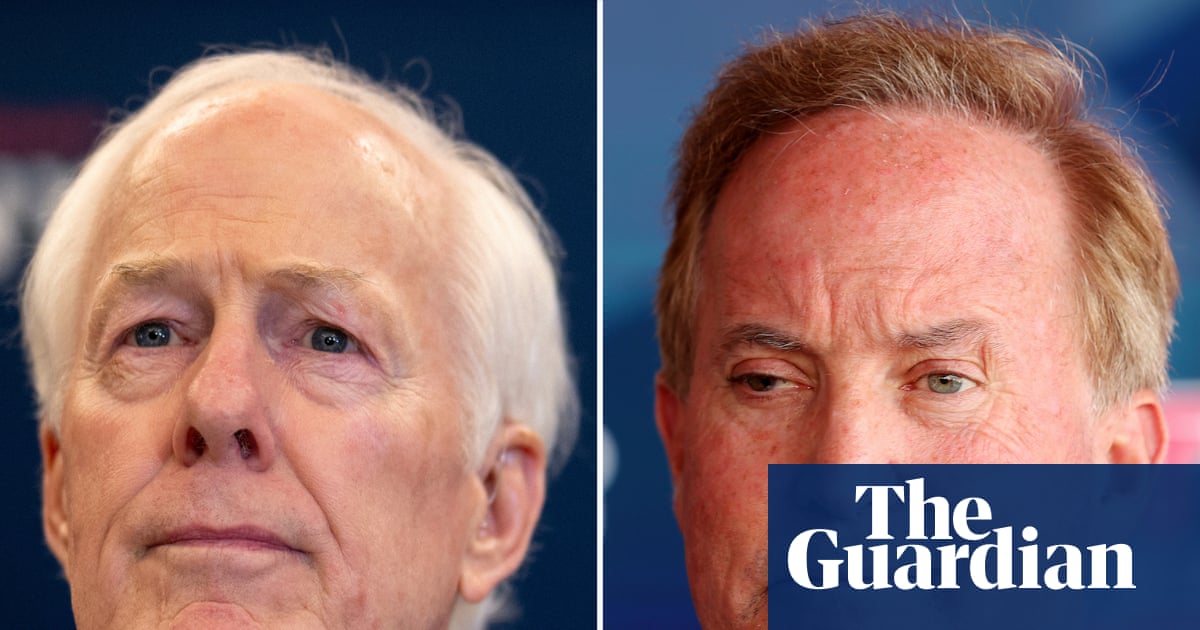

When Donald Trump announced that he would pardon the former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández, only the second world leader to be convicted of drug trafficking, Anna*, an environmental defender, was shocked.

In 2022, Hernández, also known as JOH, was extradited to the US and later convicted, along with his brother, on drug trafficking and weapons charges. He was sentenced to 45 years in prison for conspiring to smuggle more than 400 tonnes of cocaine into the US, becoming the first Honduran head of state to be tried and sentenced abroad for running a narco state. He was also accused of grave human rights violations.

During his presidency, Hernández was known for his rightwing policies that favoured extractive economies, regardless of their environmental impact. To activists such as Anna, he is notorious for the Honduran government investing nearly $72m (£57m) to expand palm oil production, which led to severe violence and deforestation that are still evident today.

As Hernández was sentenced, environmental defenders had seen the trial as rare evidence that people, even at the highest level, could be prosecuted and held accountable. Now, for Anna, Trump’s decision to erase that conviction in December last year has instead sent a clear message: Honduras’s crisis of impunity might have gained a new momentum.

Honduras has long been regarded as one of the most dangerous countries in the world for environmentalists and other activists. More than 90% of human rights violations, including murders of prominent defenders such as the Indigenous leader Berta Cáceres, go unpunished, with many cases never being formally investigated.

In 2016, the country earned the tragic title of the “world’s most deadly country to be an environmentalist” – a reputation from which it has never truly recovered. Data sourced from annual reports by the investigative environmental organisation Global Witness shows that Honduras continues to register among the world’s highest per capita killings of land and environmental defenders, while holding the record of total killings of defenders in Central America.

Toby Hill, an investigator with Global Witness, says: “The massive scale of impunity is at the root of this bleak reality, particularly as state capacity and judicial institutions are weakened by rampant corruption.”

He believes Trump’s pardon risks reinforcing the crisis of impunity, which “leaves defenders and communities exposed, vulnerable and without recourse when facing threats and violence”.

For Delphine Carlens and Jimena Reyes, respectively head of the international justice desk and head of Americas at the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Honduras’s crisis is not just about impunity but also “selective justice”.

“As soon as accountability is purely based on power, it protects perpetrators and exposes those who challenge them,” Carlens says. “Environmental defenders are targeted precisely because they challenge classical power dynamics.”

Reyes says Trump’s decision points to a pattern of “state capture”, adding: “In many cases, especially in Honduras, you have a few families owning a large share of the domestic economy, who capitalise on that power and influence the justice system to advance their interests.”

Under Hernández and his rightwing National party of Honduras (PNH), that connection became particularly visible. His government promoted extractive industries through mining, hydroelectric projects and large-scale agribusiness, often in territories claimed by Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities.

Resistance was frequently met with criminalisation, threats or lethal violence, while researchers, journalists and defenders also complained of state intimidation.

Just days after the pardon went through on 1 December, Nasry Asfura, from the PNH – the same party that governed under Hernández’s controversial two-term presidency – won the presidential election by less than 0.8% of the vote.

The election outcome was seen as a new setback for environmentalists, as the previous president, the leftwing Xiomara Castro, who took office in 2021 as the country’s first female president, promised justice, especially for defenders.

One of her symbolic moves was launching a group of independent experts to investigate the murder of Cáceres, the environmentalist and human rights defender who was killed in 2016 for leading opposition to a hydroelectric project.

Several perpetrators of her murder have since been convicted. In the new push, prosecutors have sought to fire up the investigation into those who instigated and funded the murder – a process that had stagnated for more than eight years.

Yet progress quickly stalled. Daniel Atala Midence, a member of one of the country’s richest and most powerful families and investigated by prosecutors as being behind the crime, remains a fugitive after allegedly being tipped off ahead of an arrest.

Cáceres’s case highlights campaigners’ concerns about what Hernández’s pardon and his party’s return to power imply for justice and impunity in Honduras.

“Even in the strongest case Honduras has ever had, justice is incomplete,” says Camilo Bermúdez, of the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (Copinh). “We have evidence, convictions, international attention and still the most powerful actors remain beyond reach.”

Last February, an environmental defender in the central department of Comayagua, Juan Bautista, and his son were ambushed and killed, with their bodies dismembered and discarded in a canyon. These were just two of at least 155 murders of land and environmental defenders in Honduras documented by Global Witness between 2012 and 2024, the vast majority unresolved.

Since then, no arrests have been made. Family members say the groups responsible fled the area and are expected to return once the case stalls – an all-too-familiar pattern in Honduras.

“We know who operates the logging here,” said Selvin David Ventura Hernández, one of Bautista’s sons, in 2025. “But there is nothing we can do, or we will end up dead as well. No one here will follow in my father’s footsteps.”

Reyes, of the FIDH, says Trump’s decision to pardon Hernández and the setback to justice in Honduras may have a regional impact. She says the Trump administration openly endorses authoritarian leaders who target defenders and undermine the separation of powers, which has become a new strategy for hardline governments in Latin America.

“We are observing an open embrace of authoritarian politics throughout Latin America,” she says. “When leaders who weaken judicial independence are rewarded internationally, it legitimises state capture.”

Anna, the Honduran campaigner and field researcher, says she has already observed increased pressure on communities resisting large investment projects. “There is a sense that the brakes are off again,” she says. “People feel exposed.”

Trump’s pardon, she adds, has been widely interpreted as a green light: “If drug trafficking and corruption can be wiped clean through political loyalty, what protection do communities have?”

“Justice here has always been fragile,” she says. “Now it feels optional.”

* Names have been changed due to fear of reprisals

1 month ago

33

1 month ago

33