On a fine day in early June, Ukrainian soldiers launched their latest killer robot. With a click on a screen, the unattractively named Gogol-M, a fixed-wing aerial drone with a 20-foot wingspan, took off from an undisclosed location and soared into a wide blue sky.

This “mothership” travelled 200km into Russia before releasing two attack drones hanging off its wings. Able to evade radar by flying at a low altitude, the smaller drones autonomously scanned the ground below to find a suitable target, and then locked on for the kill.

There was no one on the ground piloting the killing machines or picking out targets. The robots, powered by artificial intelligence, chose the undisclosed target and then flew into it, detonating their explosive load on impact.

Human input was restricted to teaching the drone about the type of target to destroy and the general area in which to search for it.

The reusable mothership and its killer offspring cost $10,000 (£7,500), all-in. It can travel up to 300km, with the suicidal attack drones able to fly a further 30km.

Such a mission would previously have required missile systems with a price tag of between $3m and $5m, it is claimed. “If we are financed properly, we can produce hundreds, thousands of these drones every month,” says Andrii, whose company Strategy Force Solutions designed the technology for the Ukrainian forces.

The world was dazzled by Operation Spiderweb, in which 117 Ukrainian drones struck airbases deep inside Russia on 1 June, targeting the Kremlin’s nuclear-capable long-range bombers.

Released from the top of lorries, the drones had “terminal guidance” software to allow them to fly autonomously to a chosen target in the final mile when Russian jamming systems cut them off from their pilots.

This is, however, not even the cutting edge of what Ukrainians and Russians are using in battle, let alone dreaming up.

Operation Spiderweb relied on a cunning plot to fool Russian lorry drivers into driving the unmanned aerial vehicles close to the targets. The drones were then piloted out of their hiding places. Since that operation was drawn up 18 months ago, a dearth of missile supply to Ukraine from the US, a shortage of homegrown drone pilots and the success of the Russian electronic warfare systems in jamming connections between operators and drones has delivered an extraordinary leap in innovation in the field of autonomous weapons. The Kremlin has followed suit, with Russia also able to exploit a larger production capacity.

“There is no technology that survives longer than three months as an effective measure against something,” says Viktor Sakharchuk, co-founder at Twist Robotics, which claims to be the producer of the first drones with autonomous terminal guidance systems used by Ukraine’s armed forces.

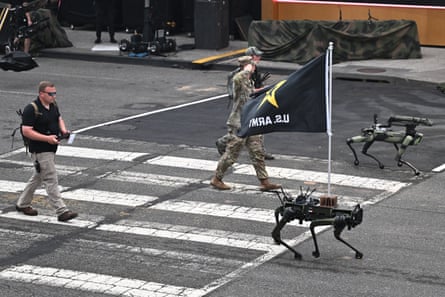

Undoubtedly, the most advanced systems in the world are being devised in laboratories in the US and China. A Pentagon programme known as Replicator 1 is due to deliver “multiple thousands” of all-domain autonomous systems by August 2025.

A first mission is reportedly imminent for the Jiu Tian, a Chinese mothership drone said to be able to fly at 50,000ft (15,240 metres) with a range of more than 4,000 miles (6,400km), carrying six tonnes of ammunition and up to 100 autonomous drones.

The dubious gift to the world from the war in Ukraine is cheap, scaleable autonomous weaponry, which is increasingly battlefield proven.

“We strive for full autonomy,” says Mykhailo Fedorov, the 34-year-old deputy prime minister of Ukraine and minister of digital transformation overseeing the Ukrainian effort in what he describes as a “tech war”.

“Our models are being trained to recognise targets to understand target prioritisation,” he says. “We do not have full autonomy yet. We use the human factor where we need to, but we are developing different scenarios for taking autonomy further.

“We are also testing some autonomous drones, which we have not announced and are probably not planning to announce, but they have a high degree of autonomy, and they can potentially combine themselves into swarms. We are still facing technical problems and hurdles, but we already see a path forward on this.”

Swarm technology involves multiple drones working together to achieve kills – a pack of predators able to devise a plan to close off escape routes and talk to each other as they go about their deadly business.

The targets are not merely tanks, planes, railway hubs and critical infrastructure. The top priority is to kill people.

“There will be cheaper autonomous systems which can target infantry at a smaller scale because this is a key target, because the doctrine of war has changed, heavy equipment is used less and less,” Fedorov says.

“The grey zone [the conflict area outside the frontline] has increased in width, and Russia attacks with small infantry groups. And our goal, our key goal, is to find a counter measure to small infantry groups. So we are looking to develop smaller and cheaper drones to use against infantry.”

The Russians are not “idle” on this either, Fedorov says.

Serhii “Flash” Beskrestnov has become a popular social media presence in Ukraine in recent years, providing real-time information on the technological developments in the war. He travels to the frontline once a month in a black VW van notable for an array of antennas on the roof.

He first came across the Russian version of the Gogol-M about six months ago, and estimates that the Russians are now launching 50 of the drones, known as the V2U, daily to strike targets near the frontlines.

One was found in Sumy city centre, 20km from the front in north-east Ukraine, but they are believed to have a 100km range.

As with the Ukrainian version, without any communication with the system operator the V2U can enter a given target area using only its visual navigation, and independently find, select and engage the target.

Beskrestnov has witnessed them swarming. “Like doves, they fly on different levels,” he says. “For us, the main problem is that we don’t understand how we can act against them. The jamming doesn’t work.”

It will take time for both sides to scale up this level of autonomy, says Kateryna Stepanenko, Russia deputy team lead and analyst at the Institute for the Study of War.

“The autonomous thinking part is still missing at large, the autonomous thinking where the drone can, just by itself, identify a target and learn from that experience,” she says. “That is where both Russian and Ukrainian forces are still trying to work with the technology and innovate further.”

Fibre optic drones, which are connected to their pilots by a wire, are the technology of the moment because they are impervious to jamming, says Olexii, chief of future battle plans in the Khartia, a combat brigade of the National Guard of Ukraine fighting on the north-eastern front in the Kharkiv region.

But the race to perfect remote killing is being run at a furious pace.

Perhaps it is the dark skies above him and the torrential rain hammering on the car windscreen, but as Oleg Fedoryshyn watches his latest unmanned land vehicle, equipped with machine gun turret, being given a run out on a muddy field in west Ukraine, the head of research and design at DevDroid is in a reflective mood.

The Ukrainian defence company is working on making this weapon-wielding machine autonomous, allowing it to operate and target without human intervention, he says.

Considerations include the avoidance of friendly fire – the robots turning on their makers.

“We didn’t know the Terminator was Ukrainian,” Fedoryshyn jokes. “But maybe a Terminator is not the worst thing that can happen? How can you be safe in some city if somebody tried to use a drone to kill you? It’s impossible. OK, you can use some jamming of radial connection, but they can use some AI systems that know visually how you look, and try to find you and kill you. I don’t think that the Terminator and the movie is the worst outcome. If this war never started, we will never have this type of weapon that is too easy to buy and is very easy to use.”

Anton Skrypnyk, chief executive of Roboneers, a Ukrainian company that develops ground-based robotic systems, says he believes the developments in Ukraine over the past year should prompt a rethink across the world about security, given the chance of the technology falling into terrorists’ hands.

“All these checks that we are going through in airports are completely useless already, so we are just wasting our time,” he says. “You don’t need to bring a bomb to blow up the plane. You can just wait outside with the drone and wait for the plane, for the prime minister.

“You can just fly into an airport, 100 drones, 1,000 drones, in automatic mode. Those drones will not be afraid of the jamming, so all your protection, which does not involve physical destruction, are useless.

“Would you put a remote weaponised station for every airport to shoot them down? What would be the budget of such projects?

“The protection of the cities should start on the level of constantly monitoring all purchases, all routes, scanning faces, understanding the patterns of the behaviour of the people, and analysing it using artificial intelligence.

“The scariest thing is that nobody cares. It is like with 9/11. Until something happens, nobody cares.”

Skrypnyk is not entirely right.

At a two-day UN consultative meeting in New York on lethal autonomous weapons in May, the foreign minister of Sierra Leone, Musa Kabba, was heard in silence. “The proliferation of autonomous weapons systems compels the international community to confront a fundamental moral and legal dilemma. Should algorithms ever be permitted to decide who lives and who dies?” he asked. “Excellencies allow me to reflect on the poem of the famous Irish poet WB Yeats in his Second Coming, when he said: ‘Turning and turning in the widening gyre; The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world; The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere; The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.’”

For eight years, diplomats working under the auspices of the UN’s convention on certain weapons have been meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, to discuss dispassionately and reach a decision by consensus on how international law should adapt to the rise of lethal autonomous weapons.

The questions raised include what level of human intervention should be insisted upon and who should be held accountable when a robot has committed an atrocity.

It has been a largely fruitless exercise. They have yet to agree on a definition of a lethal autonomous weapon let alone what to ban and what to regulate.

The UN meeting in New York was born out of frustration and convened after a resolution of the general assembly. Three countries, Russia, Belarus and North Korea, voted against it being held but 166 were in support. Ukraine abstained.

About 120 of the countries represented at the meeting indicated their backing for a new treaty similar to the 1997 anti-personnel mine ban treaty that prohibited their use, production, transfer and stockpiling.

Alexander Kmentt, the director of the disarmament, arms control and non-proliferation department of the Austrian foreign ministry, says: “The integration of autonomy into weapon systems is extremely fast paced. Most of what we see in Ukraine is still not fully autonomous, but it’s getting there.

“The vast majority want to see negotiations of a legally binding instrument as soon as possible. The vast majority, like us, would be very happy if that group of experts in Geneva makes the switch from discussions to negotiations with urgency.”

If attempts to reach a consensus were abandoned, a treaty could be adopted by the UN’s general assembly with a simple majority vote of member states.

The UN’s secretary general, António Guterres, indicated his support, telling delegates that autonomous weaponry was a “defining issue of our time” and that a legally binding instrument should be concluded by 2026.

The threat posed by lethal autonomous weapon systems, machines that “have the power and discretion to take human lives without human control are politically unacceptable, morally repugnant, and should be banned by international law”, he told delegates.

The landmine agreement, known as the Ottawa treaty, is seemingly falling apart today, with Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland announcing their intention to withdraw. But it had an impact, campaigners say.

In 1997, more than 25,000 people were killed or injured each year by landmines; by 2013, that number had fallen to 3,300.

Representatives of the Stop Killer Robots campaign, made up of more than 250 membership organisations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, were given the floor to address the delegates in May.

Humans did terrible things but they could be held to account, they said. Autonomous weapons could kill more people than intended, or different people. Their low production costs made them attractive to non-state armed groups and they were vulnerable to cyber-attacks, creating new ways for hackers to cause chaos, they said.

Russia’s delegate, sitting four rows down from the Ukrainian representative in the hemicycle at the New York meeting, did not agree. “We do not see any convincing reasons requiring the introduction of any new restriction or bans on lethal autonomous weapons,” she told the meeting.

The US is also among those that believe existing international law and national measures are sufficient to address the ethical and legal concerns.

Robert in den Bosch, the Dutch diplomat who is chairing the talks in Geneva, concedes that his mandate to consider and formulate “elements of an instrument or other measures” to address the emerging threat is difficult.

But achieving agreement through consensus is worth battling for, he says. Events in Ukraine over the past 12 months have given the extra impetus to the talks in Geneva, he claims – the British delegate was even spoken to recently for talking too quickly for the interpreter.

“Look at the Ottawa treaty,” he says. “No US, no Russia, no China, no India, no Pakistan, all important players, but not parties to the treaty. And then if things go wrong, as right now in Ukraine, with a war, with Ukraine being a party to the treaty, and Russia not. You get a situation in which not everybody is bound by the same rules. Now Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland and Finland have even decided to quit because it’s not a balanced situation.”

The world could not afford to wait, Kabba told the Guardian after his intervention in the New York meeting.

“The Ukraine war has triggered the drive for regulation … and besides also at a micro level, in our sub region in west Africa, drones are used in terrorist conflict there,” he said. “There are over 190 countries in the world, and we understand the measure of the powers that these two countries [the US and Russia] possess – but the collective conscience of humanity will always try to triumph.”

Back in Ukraine, confidence that the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice is more difficult to find after a horrifying three years of full-scale war. Oleksii Babenko, chief executive at Vyriy, a drone manufacturer working on autonomous and swarming technology says there is no alternative. “This war is an existential question for us, and you do or die,” he says.

Speaking from his government office in Kyiv after a few nights of heavy ballistic and drone attacks on the Ukrainian capital, Fedorov says Ukraine cannot afford to slow down.

“I think that parliamentarians and the ministry of defence are definitely thinking about [the ethical questions],” he says. “But it’s most important for us to find a technology which will stop the Russians, and as a democratic nation, we will consider regulation of tests after the war – as soon as the war is over.”

2 months ago

79

2 months ago

79