They are far into the lethal zone. Three people who are being held in prison on charges connected with the protest group Palestine Action have been on hunger strike for 45, 59 and 66 days. A fourth prisoner, Teuta Hoxha, ended her strike this week, after 58 days. She could suffer lifelong health effects. The remaining strikers, Heba Muraisi, Kamran Ahmed and Lewie Chiaramello, could pass away at any time. The 10 IRA and INLA hunger strikers who died in 1981 survived for between 46 and 73 days. Muraisi, whose strike has lasted the longest, is, according to supporters, now struggling to breathe and suffering uncontrollable muscle spasms – possible signs of neurological damage. Yet the government refuses to engage.

It created this situation. The Crown Prosecution Service states that the maximum time a prisoner can spend on remand is 182 days (six months). Yet Muraisi and Ahmed were arrested in November 2024, and are not due to be tried until June at the earliest, which means they will be remanded for 20 months. Chiaramello, who was arrested in July 2025, has a provisional court date in January 2027, which means 18 months in prison without trial.

The limbo of remand is often devastating to prisoners’ wellbeing. Government figures, for example, show that the rate of suicide among remanded prisoners is more than twice that among sentenced prisoners. Extreme periods of remand like these are an offence against justice.

This is one aspect of what campaigners call “process as punishment”, an approach that now dominates the treatment of protest groups. Even if you are never convicted of a crime, your life is made hell if you dare, visibly and publicly, to dissent.

The three prisoners, and others charged with the same offences, are being held under “terrorist conditions”. This means they are allowed only minimal communications and visits. They’ve also been banned from prison jobs for “security reasons”, denied books, newspapers, library and gym visits and subjected to “non-association orders”. In October, Muraisi was suddenly transferred from HMP Bronzefield, 18 miles from London, where her family lives, to New Hall prison in Yorkshire, which is too far away for her sick mother to visit. After she had been moved, she was told it was because of the risk of association with another prisoner on the same wing at Bronzefield.

Yet none of the hunger strikers has been charged with, let alone sentenced for, terrorist offences. They have been charged with ordinary criminal offences, such as burglary, criminal damage and violent disorder. Muraisi and Ahmed are alleged to have broken into a factory run by Elbit Systems, Israel’s largest weapons manufacturer, and damaged equipment, while Chiaramello is alleged to have entered RAF Brize Norton during a protest in which Palestine Action sprayed warplanes with paint. These events took place before Palestine Action was proscribed as a terrorist group, a highly controversial decision that is being challenged in court: the decision is expected very soon. But never mind the presumption of innocence, never mind the presumption against retrospective application of the law: because the CPS says there is a “terrorism connection”, they’re being treated as if they were convicted terrorists.

On 26 December, a group of United Nations rapporteurs – the kind of people who, in days gone by, were heeded by governments – expressed grave concern about the treatment of these prisoners, which, they said, included “reported delays in accessing medical care, use of excessive restraint during hospital treatment, denial of contact with family members and legal counsel, and lack of consistent independent medical oversight, particularly for detainees with serious pre-existing health conditions”. They had “serious questions” about our government’s compliance with international human rights law, “including obligations to protect life and prevent cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment”. But once you’ve labelled someone a terrorist, it seems, you can do almost anything to them and get away with it. The silence on this issue across almost all the media is something to behold.

The government bears moral responsibility for these prisoners. Yet it appears to have no intention of exercising it. Lawyers, MPs and doctors have repeatedly beseeched ministers to engage with the issue. They flatly refuse, claiming that to do so would be to “create perverse incentives that would encourage more people to put themselves at risk through hunger strikes”. There is no evidence for this, and given the extremely unusual nature of this action (it is the biggest coordinated, sustained hunger strike by prisoners since the IRA’s in 1981), it seems highly unlikely.

The government has sought to create the impression that such events are common – “over the last five years we have averaged over 200 hunger strike incidents every year” – so no unusual response is required. But what it appears to be referring to is brief refusals of food by individual prisoners, a completely different situation from an imminent risk of death by starvation.

More than 800 medical professionals have now signed a letter to the justice secretary, David Lammy, warning that prisoners face a “medical emergency”, which “is being managed incorrectly”. That letter was written on 27 November. The government has yet to respond.

Instead, it appears to mock the hunger strikers’ predicament. When Jeremy Corbyn MP asked the justice minister Jake Richards, in parliament, whether he would meet their legal representatives to try to resolve the situation, Richards answered with a sharp “No”, prompting laughter in the chamber. In December, the speaker of the Commons remarked that Lammy’s failure to respond to the MPs asking for a meeting about the issue was “totally unacceptable”. But the failure continues.

The hunger strikers’ demands seem reasonable to me: release on bail; the right to a fair trial (they claim the government has withheld key documents); lifting the ban on Palestine Action; and shutting down Elbit Systems – which has supplied weapons to a state engaged in genocide – in the UK. All these things, I believe, should be happening anyway. And they are of course negotiating positions. Whether all would need to be met for the strike to end cannot be known until the government engages. Its refusal to talk could condemn the strikers to death.

It should not be necessary to risk your life to demand fair treatment and just decisions. But when everyone in power has stopped listening, there are few remaining options.

-

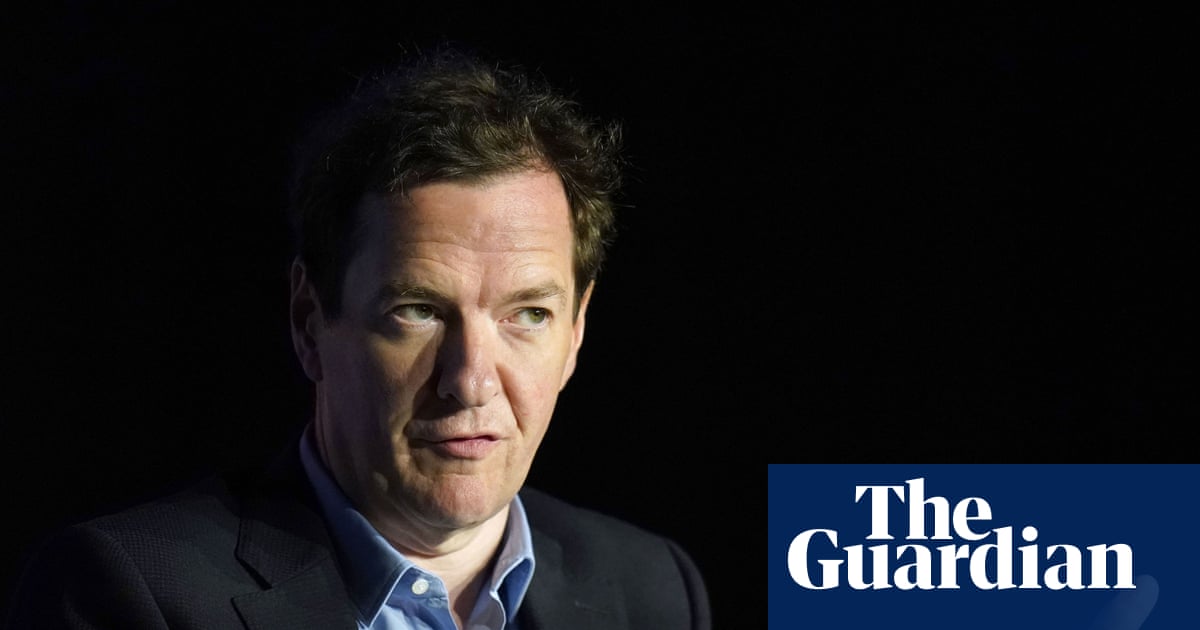

George Monbiot is a Guardian columnist

-

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

1 month ago

29

1 month ago

29