It’s good to talk. Or so men are always being told, by everyone from mental health campaigners to the women they live with, bemused by the male tendency to spend all night in the pub with friends they have known for decades and yet come back utterly clueless about whatever is going on in each other’s lives. What can they be doing, all that time? Why haven’t they asked how X feels about splitting up with his girlfriend, or how Y is coping with his father dying?

To women whose own friendships revolve around an intimate and encyclopaedic knowledge of each other’s innermost feelings, intimacy based on never seemingly talking about anything that matters looks oddly empty and sad. No wonder, we think to ourselves, that more than a quarter of British men say they have no close friends at all; that male loneliness is endemic, that they won’t go to the doctor until they are practically dying, that male suicide rates are higher than female ones, that too many middle-aged men in particular seem to feel permanently angry for reasons they can’t articulate even to themselves. Bottling everything up does nobody any good.

Yet according to the anthropologist Thomas Yarrow, that may be doing the merits of the strong and silent friendship an injustice. Prof Yarrow, who teaches at the University of Durham, was visiting a group of volunteers at a heritage steam railway in northern England as part of his research into nostalgia when he was struck by the closeness built up between these mostly older men. The four years he spent observing them have now been distilled into a study entitled “Rethinking male relationships and the value of personal reticence”, arguing that particularly for men raised in the era of the stiff upper lip, the value of friendships that revolve simply around shared hobbies – “doing things together, often in companionable silence” – may be underrated.

Admittedly, that sounds disconcertingly like the way two-year-olds interact before their social skills are properly formed, playing alongside instead of actually with each other. But according to Yarrow, this muted model of friendship “isn’t bad or anachronistic, it’s just different”. In other words: just because it’s not your idea of a friendship doesn’t mean it doesn’t count, so leave these men in peace with their trains, their golf, their tinkering with classic cars, or whatever else allows them to spend time in the company of other men who can’t stand endless yapping either.

Thankfully for anyone keen to avoid yet another culture war row about society becoming too feminised, Yarrow is explicitly not arguing that public emoting is weak or harmful, and still less for turning the clock back. Rather, he is making the point that touchy-feely talk isn’t necessarily for everyone, and that more may be going on under the surface of some seemingly repressed friendships than meets the eye. Is he right?

As a woman, I’m obviously no expert on what men talk to other men about. But as a journalist, all I can say after many years of trying to get interviewees to open up about sometimes awkward or intimate things is that while men are often more reluctant initially than women to talk, once they get going they are often astonishingly candid. A lack of visible emotion, in either men or women, is not to be confused with the absence of it.

And while younger men raised not to be so ashamed of having feelings tend to be broadly better at expressing them, anyone who has ever sat in on a focus group or been to the football will know that older men are far from incapable of it. Rebrand soppy old emotions as more acceptably masculine “political opinions” or “following Arsenal”, and an awful lot of men will happily vent their anger, yearning, disappointment or pride until the cows come home.

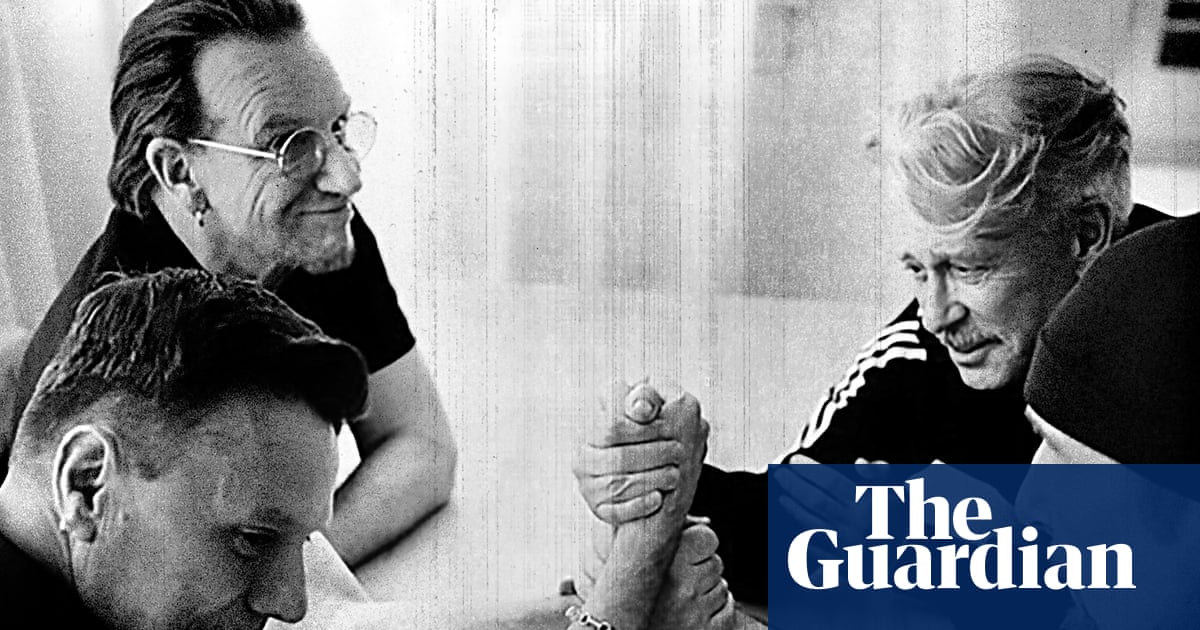

What is striking about Yarrow’s rail enthusiasts, meanwhile, is that for all their horror of talking about feelings, they were nonetheless still finding ways to communicate what looks remarkably like love and care. When one elderly volunteer failed to turn up for a few weeks and then came in struggling for breath, his friends noticed and were worried. But, the professor notes, they deliberately didn’t ask what was wrong: instead, they offered cups of tea, cracked jokes, tried to be discreetly supportive while keeping things normal. They were looking out for each other pretty much as female friends would do, except without ever acknowledging the elephant in the room.

It’s not my idea of bonding, and it may not be yours. But if the real therapeutic value of having friends – the thing that keeps loneliness at bay, and the black dog from the door – is just knowing that someone else cares enough to walk through it all with you, does that always have to be put into words?

-

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist

1 month ago

33

1 month ago

33