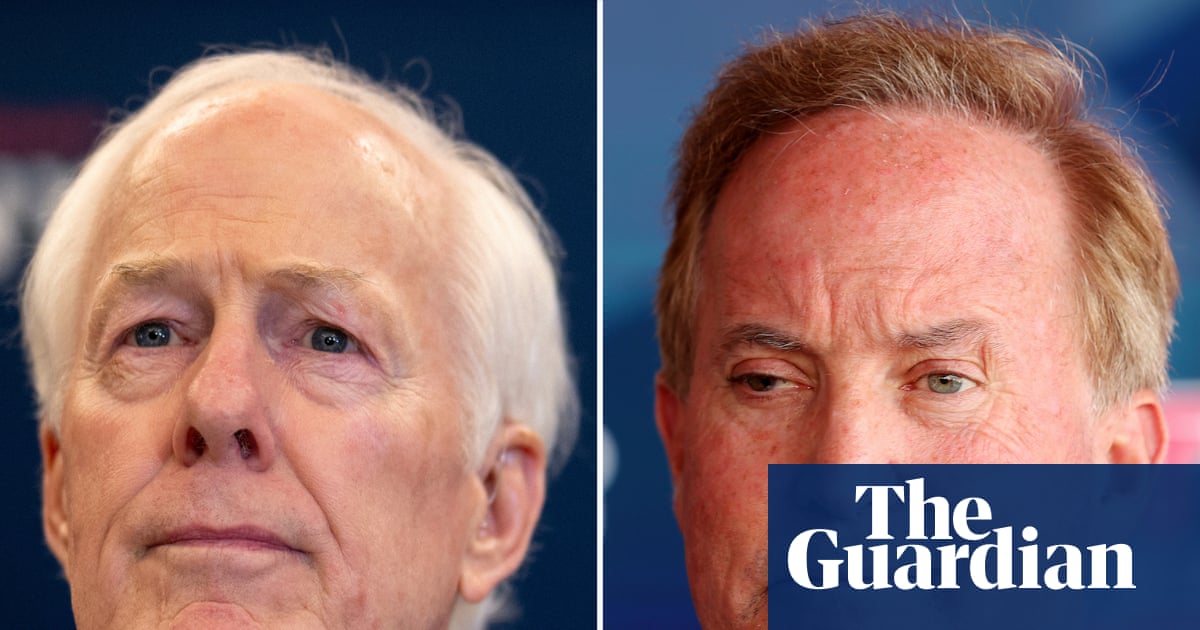

Sundance is over. Well, not quite. The Sundance we all know, with Robert Redford as its head and Park City, Utah, as its location, is over. The festival’s beloved founder died last year months after the festival also opted for a move to Boulder, Colorado.

But on the alarmingly snow-light ground, there was also chatter about what would become of Sundance as a whole, once the shining beacon of American independent cinema, after it entered a new phase. There were standout films as ever but again not quite enough to override concerns over what the festival now represents in a harsh new world where it’s arguably easier to make an indie (or whatever cobbling together bits of AI slop might be called) but harder to get it sold.

The identity of the festival has long been attached to both Redford and Utah as well as a certain type of movie and a certain definition of independent cinema. The old-fashioned dream trajectory for a Sundance movie – rapturous reception at premiere, heated all-night auction, sleeper success upon theatrical release, possibly a few Oscar nominations next – is harder, if not entirely impossible, to achieve in this landscape. There are textbooks examples of this working – films like Little Miss Sunshine, Napoleon Dynamite, Garden State and The Big Sick – but there are now more roadblocks in place as well as a generation of film-makers raised on these films trying a little too hard to conjure the same magic. Attenders, and attention-hungry critics with X or Letterboxd followings, have tried to force this in recent years, often at a high enough volume to convince studios, or increasingly streamers, to bite, but when viewed without all that altitude, hits have turned to misses. There’s been Patti Cake$, Brittany Runs a Marathon, Blinded by the Night, Late Night, and Me and Earl and the Dying Girl all barely existing outside Utah, and while there have always been Sundance gambles that haven’t paid off (Happy, Texas or Hamlet 2, anyone?), we’re at a time when each loss hits harder, risks that much less justifiable in the heads of cautious execs.

The idea of a Sundance movie has slowly shifted and stratified over time – the horror breakout, the must-see doc, the arthouse hit, the comedian-does-drama awards play, the sizzle reel for more commercial work – and this year gave us all of that and more. Again, the films that feel less calculated, less factory-made to appeal to a Sundance audience, were the ones that worked best. Last year, narrative standouts for me were films like Lurker (a dark music industry thriller about obsession and celebrity), Twinless (a genre-shifting tale of sex, lies and identity), Together (a wild body horror riffing on extreme co-dependency) and If I Had Legs I’d Kick You (an abrasive, darkly funny spiral about the exhaustion of motherhood), all uniquely formed, not calculated to speak to a past Sundance or appease the audience at a new one.

In a similar vein, the best film I saw this year was Josephine, a devastating film about the fallout from an eight-year-old girl witnessing a sexual assault told in a way we just haven’t really seen before. On paper it sounds too familiar (Serious Issue drama is another Sundance subgenre), but director Beth de Araujo turns it into something wholly original and deeply affecting, a seat-edge parental nightmare that exists somewhere close to horror without dipping into nasty exploitation. It was the film everyone was talking about on the ground (and the one I haven’t been able to stop thinking about since) and managed something relatively unusual in winning both the grand jury prize and audience award. The grand jury prize in itself has lost much meaning (Nanny, Atropia and In the Summers all recent, little-known winners), but scooping up both has tended to be reserved for films with a brighter future (Minari, Coda, Whiplash, Fruitvale Station). I could see Channing Tatum, who plays one of the more fascinatingly written and performed father characters I’ve seen in some time, gaining awards heat (I’d be shocked if he’s not a best supporting actor frontrunner this time next year) but the film is still unsold. I imagine it’s down to the difficult subject matter (the uncensored rape scene is an extremely tough watch) but also the uncomfortable way that it’s handled (I was told of a producer storming out after exclaiming, “That’s it, I’ve had enough!”).

It’s also still a slower sales market than it once was. Sundance is the most market-led film festival we have, the overwhelming majority of films going in without distribution, but buyers have become more wary – at least outside of those with the most cash (see: Netflix). At the end of last year’s festival, titles starring Jennifer Lopez, Josh O’Connor, Benedict Cumberbatch and Olivia Colman still hadn’t found buyers, while this year it’s been similarly quiet.

There was excitement over Olivia Wilde’s The Invite, which had a real slam-dunk Saturday-night premiere (Wilde called it “the best night of my life”). The sour, starry comedy, starring Wilde, Seth Rogen, Penélope Cruz and Edward Norton as two couples bickering and flirting through an increasingly revealing, and kinky, night together, played like gangbusters and, as someone who has sat through many an unfunny festival comedy that has still found laughs from an audience eager to delude themselves, this was a rare communal experience I could take part in. It led to an old-fashioned auction with pretty much every major studio or streamer making a bid, but Wilde, who has shown herself to be a craft-first film-maker who really cares about classic cinema, rightfully demanded a theatrical release and found the film a home at A24. I’d say it’s more sophisticated studio comedy than “cool” indie (more Toronto than Sundance ultimately, I was hoping Warner’s new independent label would win out) but it was a reported $12m-plus sale for a film that more than deserves it. Wilde had quite the festival, also impressing in a far different comedic role in Gregg Araki’s otherwise lukewarm dom-sub romp I Want Your Sex, earning herself belle of the ball status, something that many had expected Charli xcx to snag, starring in three films being unveiled. But her big mock doc The Moment underwhelmed and smaller, cameo-sized roles in comedies didn’t do much to reassure that her big-screen assault (there are more films to come) will be Brat-sized.

The other major sale, albeit on a far smaller scale, was a far more organic Sundance success story: a small, Australian queer horror called Leviticus. I remain cold on the rather misleading title but the film, about a conversion therapy curse that causes gay teens to be plagued by a demon looking like the one person they most desire, was a knockout. The instant Heated Rivalry comparisons felt a little SEO-inspired (gay sex did in fact exist before that show), but I think its inescapable success did help nudge a film such as this, which was heavy on gay love and lust, from a Shudder maybe to a Neon yes. The company, which has had major awards success in recent years and a hit-and-miss track record with horror, paid around $5m, which does at least take pressure off the film to become a mega-hit (last year’s $17m sale of Together led to just $21m at the US box office). With a smart campaign and an almost perfect critical score so far, it could be a nice small-scale late summer breakout, if not a Talk to Me-sized hit. It also helped to maintain the festival’s horror credentials with other offerings (Buddy, Rock Springs, Saccharine) disappointing.

Disappointments, well there were many, most of which felt like limp attempts to speak to older, better Sundance movies (overdirected and underwritten small-town dramedies like Carousel and Chasing Summer). The worst was the Dead Pigs director Cathy Yan’s star-packed art world satire The Gallerist, which wasted Natalie Portman, Jenna Ortega, Da’Vine Joy Randolph and Catherine Zeta-Jones. It was a grating, antically unfunny slog (even though, like most Sundance films, it was short, it did not feel that way), plus it had the misfortune of premiering right after The Invite, where laughs dissipated into groans. Despite that cast (three Oscar winners!), there has been no buzz over a potential sale.

The festival started on the same day as the Oscar nominations, which brought good news for last year’s narrative crop – nods for If I Had Legs I’d Kick You and Train Dreams – but great news for documentaries. Last year, four of the five nominated docs were Sundance premieres, but this year it was all five, the festival having turned into the most desirable place to premiere a nonfiction film, and while this year was lighter on more obvious breakouts, there were enough to suggest the Academy might once again turn to the festival for recommendations. The doc everyone was talking about was Once Upon a Time in Harlem, a slick assemblage of archival footage from a 70s dinner party that reunited key figures from the Harlem Renaissance. Summer of Soul, which also premiered at the fest and was a film that breathed new life into old footage also in Harlem, managed to snag an Oscar win, so while sales news has been quiet, I would expect a deluge of offers.

With whispers over who might buy what limited to mostly The Invite, most people I spoke to were more curious over what Sundance might become when it moves to Boulder. The festival has maintained a steady stream of rich Utah attenders who have very little respect for personal space (I’ve never had more jackets unfolded over or on to me in my life) but a lot of money to splash on priority passes and premiere tickets. A similar community will exist in Colorado with similarly big hats, but it’ll take time to get them onside, especially with both the Denver and Telluride film festivals already taking place in the state. What the state does have on its side is better politics (a rumoured concern for leaving Utah with an increase in anti-LGBTQ+ legislation among other issues) and more affordable lodging, a hope that a more diverse cross-section of critics might be able to attend (Park City remains absurdly overpriced).

The biggest questions are more existential. What is Sundance now? What do we want or need from independent cinema? What does the system allow or encourage as it now stands? A change of location isn’t going to change the films that are being made, and while quality might have weakened, it remains an important American institution especially as new, awful mergers threaten to squeeze out the underdog. Sundance will return next year in Colorado with a lot of expectations, and hopefully a refresh will mean sights will be set less on the old and more on the new.

4 weeks ago

36

4 weeks ago

36