Last month Dezi Freeman fled into the thick bushland of Victoria’s high country. Despite 450 police officers, members of the Australian defence force, paramilitary vehicles and helicopters tracking the fugitive, he has managed to keep hiding.

On Tuesday, it will be two weeks since Freeman disappeared into the Mount Buffalo national park, after allegedly shooting and killing two police officers and injuring a third at his residence on Rayner Track in Porepunkah, 300km north-east of Melbourne. The funeral for Sen Const Vadim de Waart-Hottart, 35, was held on Friday at the Victoria police academy, with hundreds of mourners including the prime minister, Anthony Albanese, and premier, Jacinta Allan, attending. A funeral service for Det Leading Sen Const Neal Thompson, 59, will take place on Monday.

Since Freeman, also known as Desmond Filby, fled into the bush, speculation has swirled around how he has managed to hold out in the harsh alpine terrain. Police have also acknowledged the possibility he is being harboured or helped by people in the community.

The police have said they are committed to catching the alleged killer, but many locals say if he is in the bush, he will never come out; his bushman skills are too good, his knowledge of the area too great, the list of hiding places too long.

Years ago, Ray Kompe took Freeman walking around Mount Buffalo, showing him the mountain, saying the pair became “good friends” before the fugitive fell in “with the wrong crowd”.

“I took him up there, and it was just a great epiphany for him,” the Porepunkah resident says.

Freeman’s love for the high country “became more intense”, he took up photography and Kompe took him on walks to places including Dickson’s Falls.

On Friday, Kompe is leaning on his gate with his dog Luna in his hands. A convoy of police have just searched his home, one of hundreds that have been searched over the past 11 days. Kompe says he has not seen Freeman properly in 10 years now and he is not accused of any wrongdoing.

“We used to do a lot of crazy walks … but then he fell into the wrong crowd,” he says.

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

Kompe says Freeman became more ideologically extreme and would talk about how he “had a great disdain for Australian women”. The two men would say hello if they passed each other in the street in Bright, but as Freeman’s views changed, their friendship waned.

“It was just like a switch that was switched off, and that was basically as he started to become a bit radicalised,” he says.

Kompe says he taught Freeman how to move through the bush without using the paths, instead bushbashing through the thick scrub. Freeman learned where the mine adits in the area are. He says they hold heat exceptionally well and can be 18C even at night.

“He just loved the bush, and I was probably the catalyst for all of that,” Kompe says.

“He’s become very proficient at getting around it.”

‘You can’t remain hidden forever’

Survival experts say Freeman’s chances of evading capture are growing slimmer as the days go by.

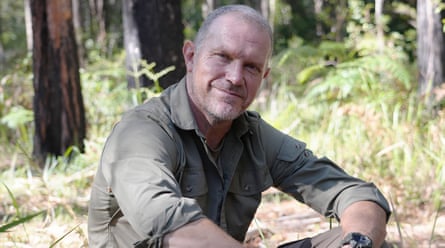

“You need shelter. You need water, and you need to be able to eat eventually,” says the founder of Bushcraft Survival Australia, Gordon Dedman. “And you need to be able to do it without being caught.”

By now, Freeman’s body would be under immense stress, Dedman says, with his likelihood of outlasting the search dwindling.

Dedman says enduring the harsh conditions in the bushland of Victoria’s high country relies on four principles – protection, location, navigation and acquisition of essentials including water and food. Protection will be the most important for Freeman, he says, and that includes first aid, clothing, shelter and fire.

Dedman says the first thing Freeman would have worried about was his clothing. When he took off up the bush, he was wearing dark khaki tracksuit pants, a dark green rain jacket, brown Blundstone boots and reading glasses – but he would need wool or thermal and waterproof outer layers to survive, Dedman says.

“If he has got that – maybe he had a stash of it somewhere – that’s going to be aiding massively,” he says.

The weather has been hard to search in, and hard to survive in. There have been huge winds, days of rain and blizzard-like conditions. Overnight temperatures have dipped as low as -1C.

Location and navigation are less important; he does not want to be found, and he knows the bush well.

“Acquisition is water, then food, because water is more important,” Dedman says.

Water is likely plentiful – the search has focused on the area around Ovens and the Buckland River.

after newsletter promotion

“For short-term survival and up to 10 days, food is not an issue,” Dedman says. “It’s the last of the priorities. But from now on, for him, it will start being an issue. If he doesn’t have resupplies, he’s a hunter, but is he able to hunt?

“That means he’s using a firearm, unless he has a hunting bow. But anything he does is going to attract attention. That’s what he’s going to be trying to minimise.”

Freeman was a member of the Australian Preppers Facebook group and there are concerns he could have stashed supplies and gear across the mountain.

Holly Robertson, who runs Australian Bush Survival School, believes he has “gone underground or a shed or somewhere that’s warm” to survive the cold weather.

If he is still moving through the bush she says his body would be under a “massive amount of stress” and bushbashing, even with a machete, would be hard. In the cold, he would be losing calories quickly.

Victoria police are increasingly concerned people in the surrounding area are helping Freeman. Since the alleged killings, they have searched hundreds of properties, with human scent-trained dogs, homing in on caravans and sheds.

But Robertson says there are ways to cover your own scent – animal urine, dirt, smoke. After a few days, especially if Freeman is eating food from the bush, his smell would change and the dogs may not be able to pick up his scent, she says.

Freeman’s biggest defence is the bushland and his own knowledge. But the fact police get to rest and refuel gives them the upper hand, Dedman says. Stress and exhaustion mean he will eventually make a mistake.

“People always do something to mess up in the long run,” he says. “You can’t remain hidden forever.”

How will this end?

The Macquarie University criminologist Dr Vince Hurley says police have been quiet about their tactics and plans on purpose – it is likely Freeman is getting updates about the search, either by radio, a phone or through friends.

Hurley, a former police negotiator, says when they find him, and he believes they will, they will then monitor him for 48 hours.

“The reason for that is to get an assessment of his physical condition, as well as his psychological condition,” he says.

“Is he behaving erratically? Is he injured? Does he have food? Does he look reasonably well nourished?”

Hurley says it is “highly unlikely” police would do anything to aggravate him or trigger him to retaliate. Because there is no immediate threat to the public, but a large one to officers, they “won’t storm the place”. Instead, they will see if he will negotiate.

Police will surround him, using a microphone to talk to him. They will start with open-ended questions, asking how he is feeling and what he is thinking to assess his mindset. They will tell him they want this to end peacefully, Hurley says.

At this point, there are two options. Freeman can choose to go down “in a gunfight” or cooperate with police, Hurley says. If it is the latter, they will tell him to put his hands in the air. They will get him to take five steps towards them, before giving a set of instructions and asking him to repeat them.

Hurley says at this point, Freeman will be nervous, exhausted, suffering from a lack of sleep, and possibly food, which will all be impacting his thinking. Police will tread carefully.

“To bring it to a peaceful resolution,” Hurley says. “They want to get him to court so he is answerable to the law, but also to give closure to the families.

“But how this will end will depend upon him.”

3 months ago

54

3 months ago

54