Tea and cake. Cobble-close streets. Collectivism. Sugar rush. Hollywood fairytales. And also, as of this week, a minority owner with historical links to celebrity paedophile Jeffrey Epstein.

Wait! Welsh cakes! Welsh tea! Aggregated tourism benefits. The sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea. And also, at one remove, historical links to deceased celebrity paedophile financier Jeffrey Epstein.

Two important things have happened to heartwarming Disney TV vehicle Wrexham AFC in the past fortnight. First it was announced that a grant of £18m would be provided by the Welsh Labour government to help renovate the Racecourse Ground, which is unusual, public money to a private entity, but justified as part of a wider regeneration.

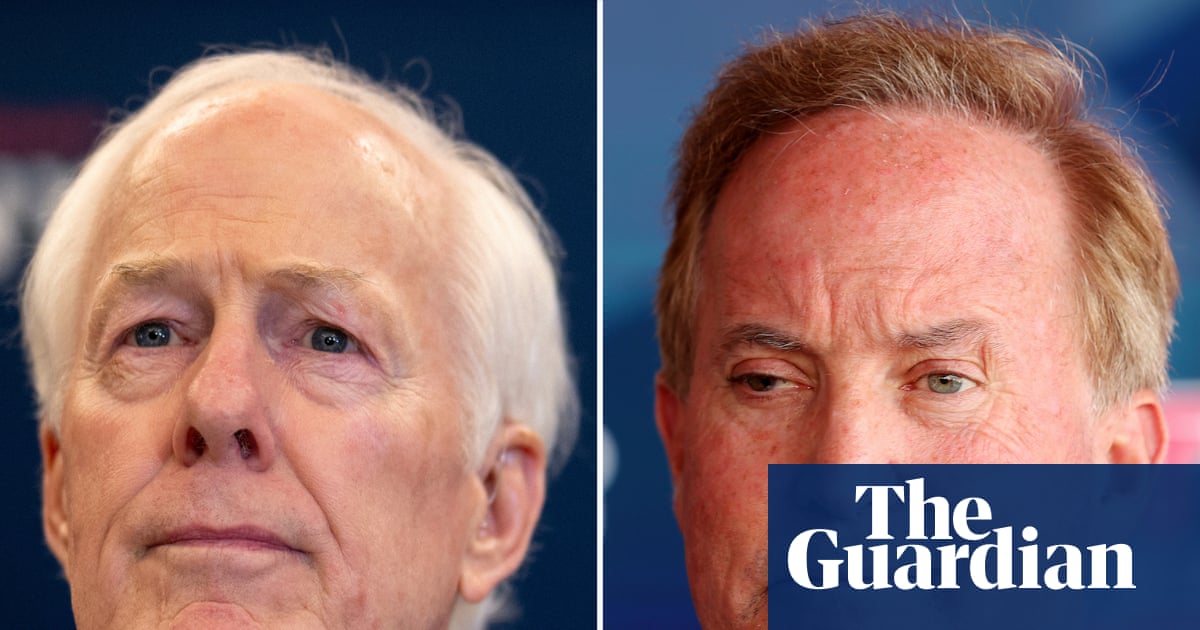

And second, Wrexham’s co-owners, the TV guys, Rob and Ryan, announced the sale this week of a minority stake to Apollo Sports Capital, which is owned by Apollo, a US hedge fund.

Now. It is important to state that the new minority owner of Wrexham has no current links to Epstein. Those links were severed in March 2021, which is a whole four and a half years ago, when one of the cofounders of Apollo, Leon Black, resigned from the board after it emerged he had paid Epstein $148m in return for some kind of personal financial advice, and had also – hard to get past this one – written a mildly salacious poem in Epstein’s 50th birthday card.

So, zero connection. You could be of the view, if you wanted to be pedantic here, that the financial muscle of Apollo was built in part through the expertise of a guy who wrote: “Blond, red or brunette, spread out geographically” in a paedophile people trafficker’s birthday card, which is middling verse, but top-of-the-range creepiness.

But Apollo Sports is a legit fund, provides a necessary service, and has purged itself of its seemingly dodge-pot founder. We know how this world works. All hedge funds seem dirty at one remove, because money is dirty. And all football clubs at this level are owned by people who have money.

The most obvious point of dissonance is the grant of public funds. Why is the Welsh administration giving money to an entity now part-owned by US financiers? Why are they doing this at a time when the NHS is ailing and infrastructure in decline?

The new minority owners have limitless finance available to them. They can build a stand and fix some floodlights. If the world were run on morality and fairness this money would now be returned to the public purse. It isn’t and it can’t, so it won’t.

But let us be fair to Wrexham here. There are plenty of whatabouts. Who built the Etihad Stadium? Who built West Ham’s Olympic-scale temple of sadness? In the end, it was you and me. And let me please introduce you to Sir Big Sir Jim Ratcliffe, also seeking public money to boost his rebuild of Old Trafford’s surrounds.

This can be addressed. When the state regulator gets to work, its role should involve scrutinising exactly this kind of situation. For now it will continue to happen, because things need to be built, the UK has so little spare capacity, and the cap must always be out there upturned on the pavement.

It may be depressing that this is our notion of growth now. Could the public money have been used to generate jobs in a way that doesn’t rely on a US TV show being recommissioned for another series? But there is also the hard reality of jobs and economic activity. The creation of a tourist hub in a town notable previously for possessing the biggest slag heap in the Western hemisphere may be one of the strangest things that has ever happened in British football. But it has also worked, at least for now.

The real point here is the people around the table now. This is information. Wrexham is telling us what it is, and what football is. This has always been a TV product, to some extent a useful lie, investment disguised as a buddy-tale underdog story.

They’re not even buddies! Wrexham’s owners met for the first time filming the show. But it’s also great casting. They work on screen, wandering around Wrexham like handsome alien royalty, entirely believable as regular-dude fairy godmothers refinding their own blue collar blah‑di‑blah, like Reese Witherspoon in Sweet Home Alabama, but with middle-aged gym muscles and teeth that look as if they were made in Dubai by a robot.

But wait! They do have a fish-out-of-water everyman-type figure as club director, Humphrey Ker, who looks like someone created if you asked AI to make an image of an agreeable man from the 1990s who likes pesto and the music of Shed Seven. But Ker is also a construct, an actor, comedian, TV impresario and scion of the fourth earl of Cheese-Flaps or similar, the kind of Englishman who in another life would be striding around in massive starched shorts being Governor General of Bechuanaland.

Humphrey found the right club, did the work, recognised that if you’re going to monetise grit and heritage then selling warm, underdog Welshness gives you bang for your buck.

Strip this stuff out, front-load it, present it to America. And with the arrival, finally, of the hedge funders, there is no pretence now. This is just another project, as it always was, albeit an interesting one. Even the financial doping element, often mentioned by fans of rival clubs, is nuanced. Wrexham have powered their way up the leagues not with magic or story-telling but with hard speculative cash, £40m or so over five seasons, the biggest net spend of any Championship club this summer according to Transfermarkt, a transfer net outlay bigger than any club in the Bundesliga.

But this is also just what you have to do. You can’t make the journey without constantly regearing your squad. Most importantly, it is also sustainable, because Wrexham make a huge amount of commercial revenue. It is in its own way a model of financial probity, of eat-what-you-kill good sense capitalism.

This may involve a televisual illusion. But it’s workable. It won’t fail the profitability and sustainability rules. This is also a historically powerful club with the reserves and interest to function on this scale. It provides social benefits, has made the town pulse with life, made people happier.

It is also far from an anomaly. Rather, Wrexham is part of the same process that is happening everywhere, the new model of US sports capitalism that views this industry as an under-leveraged global entertainment product ripe for the streaming age.

Premier League owners will talk openly about the dream of piggy-backing football for its unique quality of cut-through, creating a new global platform around it, making real Zuckerberg billions, Google billions, leveraging the endless hunger for content.

Wrexham are a part of the same process that means Mo Salah not playing football is the biggest story of the season so far for eyeballs and dramatic energy. It’s part of the same dynamic that means the Word Cup is unaffordable, because capitalism says you will pay what we can make you pay and that is good and right and just a functioning market.

Good art, good TV, good dramatic writing always tells you about the world around it. Wrexham have done this in the guise of a rootsy fairytale. But they will also take your public funds, will do what they must to grow their footprint. As the project heads towards the overclass tier, driven on now by that mix of schmaltz, theatre and sharp-toothed finance, it is at least doing it right out in the open.

2 months ago

39

2 months ago

39