‘All paintings are in their own way accusations and confessions,” says Joseph Yaeger. “It’s what Polygrapher is about.” This is the title of the artist’s new exhibition, his first since joining the prestigious London gallery Modern Art in 2024, for whom it marks the opening of new premises in St James’s.

Honesty is important to Yaeger, whose upbringing in the US in Helena, a town that he says ambitiously calls itself the capital of Montana, was as decent as it was unremarkable. “We’d sit down for dinner together every night, we’d go to church every Sunday, we’re polite almost to a fault, and traditional in almost all senses of the word.”

His prodigious work ethic is further evidence of a sound upbringing: when we meet in his studio, a week or so before the exhibition opens, the 17 paintings to be included in Polygrapher are long gone and the wall is covered instead with canvases headed for his New York gallery, Gladstone, next year. “I work many, many months ahead, probably just as a way of dealing with my own anxieties,” he says with a hefty dose of self-deprecation.

Though his early ambitions as a film-maker were halted by the realisation that he is “a very, very poor manager”, his paintings are the result both of meticulous planning and happenstance. “Truly,” he says. “A lot of times the work just happens in front of you.”

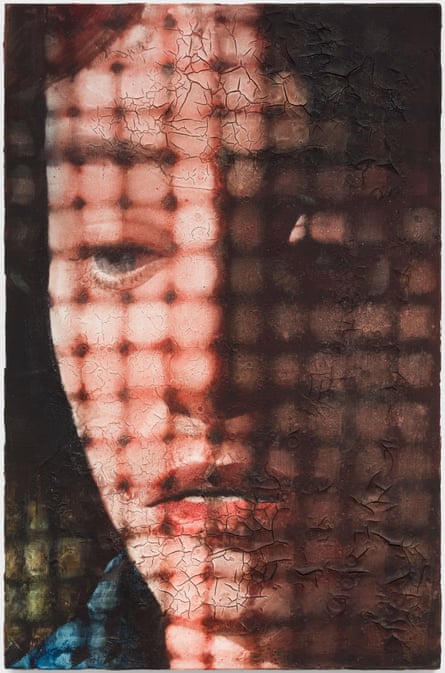

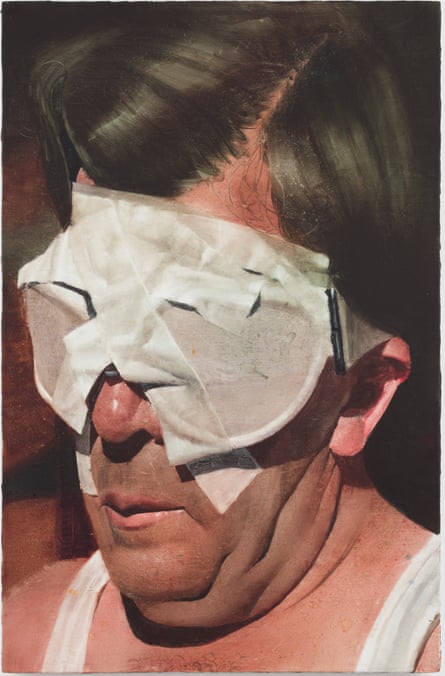

Now 39, Yaeger graduated with a Master’s from London’s Royal College of Art in 2019, and is now much talked about in art circles. He works exclusively in watercolour over gesso – a white, hard-drying primer traditionally made with gypsum – on canvas or linen. You wouldn’t guess it: from a distance, and in reproduction, his paintings, many of them monumentally large, look like film stills, with the shine of a wet lip or the papery crease of an eyelid preserved in glossy, hyperreal intensity. It’s only when you get much closer that their surfaces disclose scars and pockmarks, and deep, regular cracks like those of a drought-ravaged river bed.

The people he depicts are indeed taken from film stills snipped from their original contexts. The touch of the artist, meanwhile, is visible in the fragments of pistachio shell, clumps of dust from the studio floor, or foil wrapper from a biscuit, forever bound to the picture surface like a dog’s footprint in wet cement.

Yaeger writes a text for each exhibition. In this case it is the transcript, we are told, of a polygraph – or lie detector – test undertaken by the artist, in which only his answers are revealed. It’s a meandering, fragmentary document in which a voyeuristic encounter with a neighbour is interwoven with what seems to be memoir, concerning his work, his daughter, his Catholic upbringing and art criticism.

So did he take really take a test? “In all important senses,” Yaeger says cryptically, adding that he thought the polygraph “was debunked ages ago. As a means [of discovering the truth] it’s clumsy and kind of stupid. But as a metaphor, there is just so much meaning that goes down into this feeble little machine, it’s really powerful and dark. It doesn’t surprise me that the Trump administration is using polygraphs – it’s very Trump-administration coded.”

In place of the polite compliance of the transcript, the paintings are dangerously ungovernable, like fragments of raw memory. Is a face held with violent force or erotic passion? Are eyes hidden behind a mask complicit or terrorised?

after newsletter promotion

“Once the text is finished, I begin sifting through my archive of collected images and memories,” Yaeger says. “I end up in these intense flow states – you’re completely gone as a conscious mind when you’re painting, disappearing into an interior that you can’t find language for when you come back out.” The fact that so much darkness emerges in the paintings is all part of the adventure. “There are no deep, unending, psychic wounds,” he says of himself. “I think probably you’re just born with melancholy.”

Though lapsed, Yaeger’s Catholic upbringing is hardwired and Clean Windows Kill Birds, in which a woman’s face is seen through the screen of a confessional booth, is one of many hundreds of overtly Catholic paintings he has made. A penitential streak draws the artist to the difficulty in his work – the hours spent painting on the floor, battling the fundamental incompatibility of watercolour and gesso.

Partly as a result, there are many dead paintings beneath the surfaces, the evidence of which is visible on the bare edges of the unframed canvases, which are thick with layers of encrusted gesso and pigment. The thing about gesso, says Yaeger, is that the paint can be completely removed: “I could erase this to nothing.” Instead, at the painting’s edges, he tells a different story – perhaps the most important story of all, about our need to make a mark, to leave a trace.

-

Joseph Yaeger: Polygrapher is at Modern Art, 8 Bennet Street, London, 15 November to 17 January

2 months ago

36

2 months ago

36