Spain makes the best ham in the world, and a multitude of incredible pork-based dishes. You have your crunchy, salty torreznos de Soria, fried cubes of pork belly, which make for a fantastic bar snack. Or cochinillo asado, a suckling pig that’s traditionally roasted in a wood oven, and so tender that it’s cut with a plate instead of a knife when serving. For the more adventurous, I recommend exploring the world of regional morcillas or blood sausages. Morcilla de Burgos, made with rice and on the harder side, keeps its structure very well and makes an excellent pintxo when sliced and fried. Or there is the moist and spreadable morcilla de León, which my local butcher sells in jars. Another to look out for is the Basque morcilla de Beasain – made with leeks, it combines fantastically with black beans, cabbage and pickled green chillies to make one of the tastiest stews you’ll ever have.

At the pinnacle, you have the gastronomic and cultural phenomenon that is jamón ibérico. It is distinct from lesser forms of jamón as it comes from the famed Iberian pigs, the best varieties of which are fed on acorns. You’ll see whole legs of it hanging in bars and restaurants across the country, and they’re a staple of the Spanish Christmas hamper, often raffled off by bars to their regular customers. Its standing in Spanish culture transcends the food world: Javier Bardem and Penélope Cruz met while filming Jamón Jamón, in which the former beats his love rival to death with a leg of ham. Meanwhile, lower-league football side CD Guijelo’s away kit sees them dressed as a plate of the stuff. It finds its way into Spain’s public festivities, such as the Lance al Jamón in the walled city of Morella, where participants have to climb its walls and grab a leg of ham hanging from the ceiling. The contestant able to hang on the longest gets to keep it.

For all the happiness it brings to people, jamón also has a darker history and it is one that is threatening to re-emerge in our present culture wars. The esteemed place jamón holds in Spanish culture has been used as a tool for social exclusion. The persecution of heretics during the Spanish Inquisition, beginning in 1478 and lasting almost four centuries, particularly targeted Christian converts from Judaism (conversos) or Islam (moriscos), who continued to practise their religion in secret. The consumption of jamón became a symbol of Catholic identity and therefore a huge part of Spanish public life. But it was also a way of excluding those who did not eat pork on grounds of their faith.

As a way of getting around it, morisco and converso families would hang sausages in their houses. Indeed, some people speculate that this is how the practice of hanging sausages and hams in Spanish bars and restaurants started. Others would even cook ham that they had no intention of eating, so that the smell from their houses would waft to neighbours or passersby. The slaughter of pigs became the basis of many popular festivals, a number of which continue today, and the families who did not take part would immediately come under suspicion.

This has left a lasting impact on Spanish cuisine. “Because of the Inquisition,” wrote food science expert JM Mulet in his 2023 book Comemos lo que Somos (We Eat What We Are), “most Spanish traditional dishes contain ham or are cooked in its fat like there’s no tomorrow”. It’s a legacy that goes beyond food and is at the heart of Spanish culture. The second sentence of Don Quixote mentions the dish duelos y quebrantos, comprising scrambled eggs, chorizo and torreznos. It literally translates as “grief and sorrows” – and while its meaning is disputed, a popular interpretation is that this refers to a converso’s internal struggle with having to eat ham to avoid suspicion of heresy.

I’m not sure how widely understood the Inquisition’s legacy on the Spanish diet is, but seeing history repeat itself is a sign that the past has not been fully reckoned with. So while I’m not here to stop anyone from enjoying their favourite foods or traditions, I’d like to sound a note of warning. Jamón eating is once again being weaponised online as a means of social exclusion among the young Spanish far right against those from Muslim and north African backgrounds.

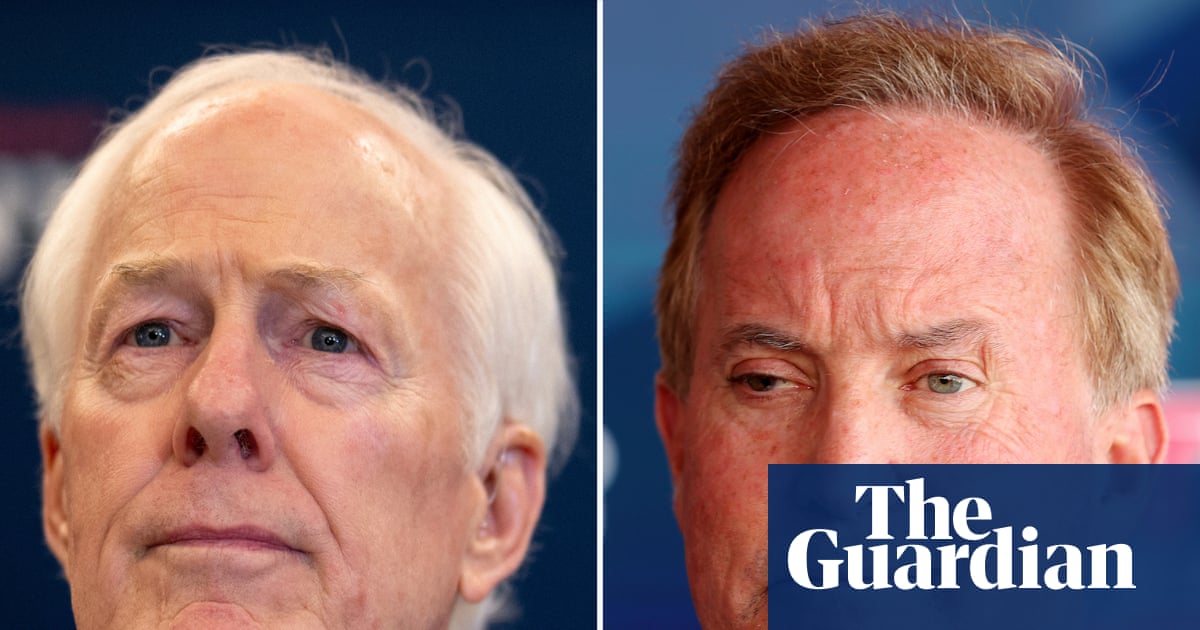

Last November, a content creator made national news when he shared AI-generated viral posts showing shirts and phone cases made from jamón. The posts even featured a superhero called Ham-Man, who would, he said, protect people from being mugged by illegal immigrants of “Maghrebi and north African origin”. And it risks becoming a wider trend. Even before Ham-Man, the comment sections beneath Spanish news articles and videos about crimes committed by young, racialised men elicited dog-whistle phrases such as “¿come jamón?” (does he eat ham?). This meme has been popular for a number of years among the Spanish far right as a way to persecute Muslim immigrants.

When prejudice like this is allowed to go unchallenged in the form of social media memes and reels, it inevitably spills over into real life. After Spain won Euro 2024, a video went viral of a group of fans chanting “Lamine Yamal come jamón” (Lamine Yamal eats ham). This references the north African and Muslim background of the young superstar of the national team, despite him being born in Barcelona. “He’s one of our own” is a popular sentiment in football chants – but I struggle to think of one as perverse as this.

You can be born in Spain, score the goal of the tournament that wins the semi-final and provide the assist for the opening goal in the final – and yet for some Spaniards, the Inquisition hasn’t ended. For those looking to divide and exclude, ham is still a weapon of choice, half a millennium later.

-

Abbas Asaria is a food writer and chef based in Madrid

4 weeks ago

31

4 weeks ago

31