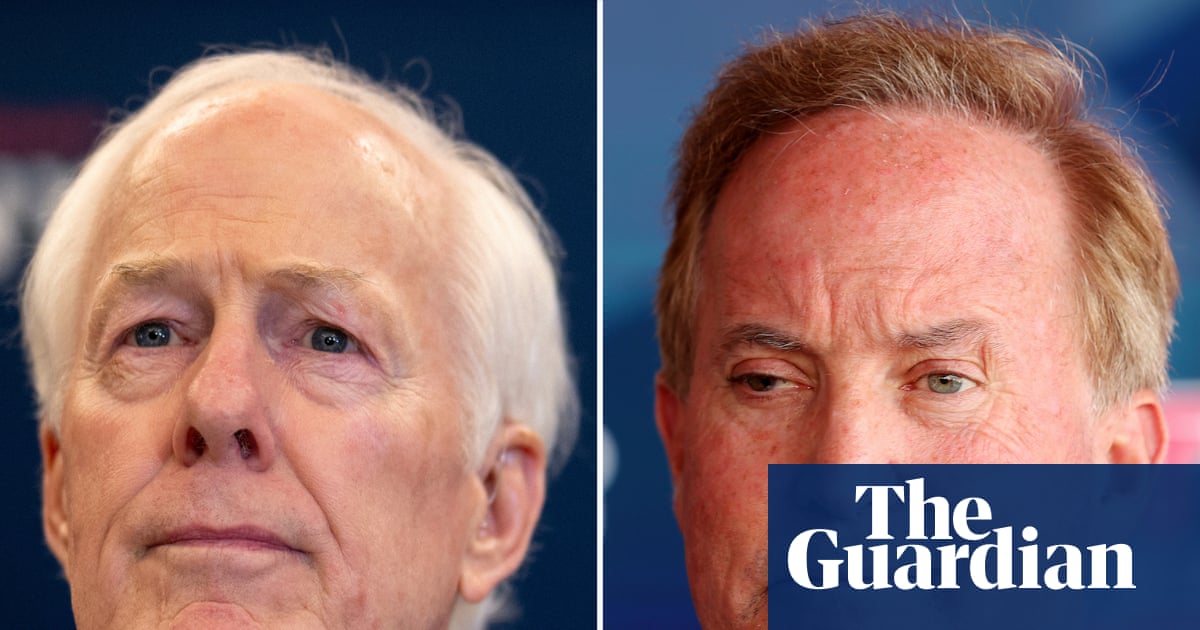

A fairly technical-sounding change to student loans tucked away in last November’s budget has become the catalyst for an increasingly bad-tempered row pitting the UK consumer champion Martin Lewis against the chancellor, Rachel Reeves.

In one interview, Lewis – the founder of MoneySavingExpert.com, who boasts a vast following – said he did not think the planned change to repayment terms “was a moral thing”.

Reeves has defended herself and insisted the student loans system is fair, but with Lewis all but demanding that millions of graduates rise up and write letters to their MPs to say “this isn’t on”, this bust-up looks likely to snowball further.

A YouGov survey published on Monday found that the public is divided on the issue of student debt. More than four in 10 Britons – 44% – said the government should write off some or all student debt. But 41% said graduates should have to pay back their loans as currently.

Here we look at what the row is all about.

Why exactly are Lewis and Reeves at loggerheads?

The disagreement is focused on the estimated 5.8 million people who took out a student loan between September 2012 and July 2023.

For many of these graduates, everything they hand over from their salary is dwarfed by the interest that is slapped on their debt every month.

What prompted the latest row is Reeves’s decision to freeze the salary threshold forrepayments for “plan 2” student loans for three years – which means many graduates will now have to pay even more.

This salary threshold, above which plan 2 graduates have to repay 9% of anything they earn, will rise to £29,385 in April this year, and normally it would have been expected to then rise again each year. However, Reeves announced it will stay frozen at that level until 2030.

Freezing the threshold as wages go up means more people will be pulled into the net and have to start repaying their loans as the amount they are earning goes over the limit. Those already over the threshold who get pay rises will have to repay 9% of a bigger chunk of their earnings.

I don’t really understand student loans – can you run me through the basics?

It’s a very complicated system, so here’s the short and simple version. Student finance is made up of a tuition fee loan that covers course fees, and a maintenance loan designed to help with costs such as rent and food.

Both need to be paid back, and interest is added each month until the debt has been repaid in full or written off.

There are five repayment plans – you don’t choose which one you are on – and the Lewis/Reeves row involves plan 2 loans, which were taken out by students from England who started university between September 2012 and July 2023, and students from Wales who have started since September 2012.

The vast majority of outstanding student loan debt involves plan 2 loans: a total of £213bn at the end of 2024–25, said the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

As plan 2 graduates currently have to repay 9% of everything they earn more than £28,470 a year, that means that if someone is earning £38,470, their annual repayment is now £900. The more you earn, the higher your monthly repayments will be.

The interest rate on plan 2 loans is linked to the RPI rate of inflation and can vary from month to month: in August 2024 it hit 8%.

The Guardian reported in September that more than 2.6 million people in the UK owed £50,000-plus in student loan debt, and that just over 150,000 owed more than £100,000 – prompting claims that these “debt sentences” are damaging graduates’ ability to save for the future and get on the property ladder.

There have been frequent calls for student loan debt to be rebranded as a graduate tax. It certainly works like one: plan 2 graduates simply pay 9% of everything they earn over the threshold, regardless of how much they owe, and it is collected through the payroll, just like income tax.

Crucially, the loans are written off after 30 years, and most plan 2 borrowers will never repay their loans in full.

But, say many students, that is a very long time to watch your debt get bigger and have to hand over money from your pay packet.

What does Martin Lewis want?

He said his message to the chancellor was: “I do not think it is a moral thing for you to do to be freezing the repayment threshold in this way … You didn’t say the terms were variable. This isn’t right. Please have a rethink.”

Lewis added that in his opinion, students had a contract, and the government was “unilaterally changing the terms. You tell companies they can’t do that – you shouldn’t do it either … It would not be allowed for any commercial lender, it would go against all forms of consumer law.”

He added that freezing the salary threshold “is a breach of contract – it’s a breach of promise”.

Lewis suggested that all of the millions of plan 2 graduates affected by this could write to their MPs to say that “this isn’t on – this isn’t what we were promised”.

What does Reeves say?

She said it was “not right that people who don’t go to university are having to bear all the cost for others to do so”.

She told LBC: “It is important that you don’t have to start paying back the student loan until you earn enough money.” She added that if a graduate was able to get a job that paid a good wage, they would pay that money back more quickly. “But if you’re never able to repay, that loan will eventually be written off. I think that is a fair system.”

The Department for Education has said: “This government is making fair choices to make sure the student finance system is sustainable – protecting taxpayers and students.”

What do others say, and what happens now?

The National Union of Students (NUS) has said the salary threshold freeze could leave new graduates struggling to afford food, rent and bills.

In a report last month, the IFS Institute for Fiscal Studies quantified the financial hit that graduates would take from Reeves’s move. It said that as a result of the freeze, it expected that millions of plan 2 people would repay an extra £93 in 2027–28 – rising to an extra £259 in 2029–30.

Crucially, it said the combined effect of all the threshold freezes announced in the budget meant someone who started a course in 2022–23 would repay an average of about £3,200 more over their lifetime. To put it another way, their expected lifetime loan repayment would go up from £52,600 to £55,800 (in today’s prices).

“These latest freezes mean that in the long run, we now expect the taxpayer will pick up almost none of the bill for financing the higher education of this cohort,” was a key sentence in the IFS report.

The debate will now continue as to whether graduates should meet almost all of the cost themselves, and whether that is a fair way to divide up the bill.

Politicians and campaigners will now be watching closely to see if Lewis’s “write to your MP” idea gets traction, and whether this issue might shape up to be one that could cost Labour at the ballot box. The government may welcome the YouGov poll’s findings as demonstrating that there is much disagreement among the public about how the bill should be financed and who should pick up the tab.

4 weeks ago

33

4 weeks ago

33