On a recent Friday morning, the chapel of San Quentin prison was abuzz as more than 100 incarcerated men and their friends and families took their seats at tables filling the room. A banner with large orange lettering hanging at the front read “Arms Down: Teaching there are options between the first and second amendment”, and the mood was festive, with the men hugging their spouses, parents and siblings.

Now sheltered from the foggy, misty Marin county morning, participants and leaders of this first-of-its-kind program stepped onto the stage and started to talk, about mistaking being feared for being respected, about living with unaddressed trauma, about leaning into misconceptions of manhood and how that led them to rely on firearms as a source of safety and power.

Some of the men grew up in communities where, as children, they heard gunshots and saw people shot, while others’ first exposure to guns were in movies and on television shows. But for all of them, guns became a necessary part of life, like a wallet or a set of keys. And all of them, at some point, used a gun to severely injure someone or take a life.

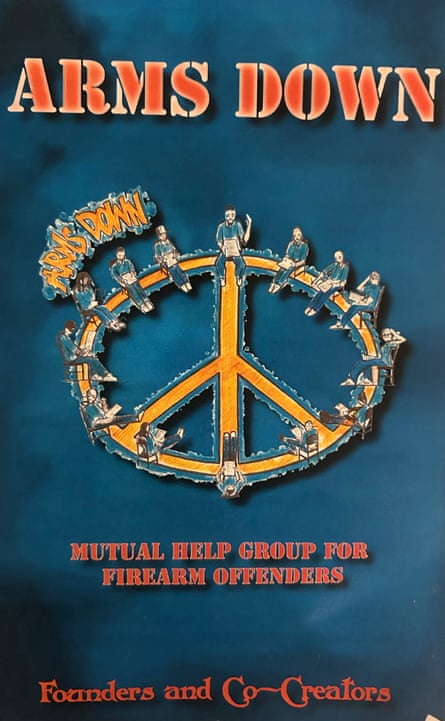

Arms Down is a “mutual help group for firearm offenders”, meant to help incarcerated people understand the reasons that they carried and used guns. Understanding will lead to healing, the program’s creators hope, and insights the men gain in the program will travel beyond the prison’s walls and help reduce violence in the free world.

“This is an opportunity you have to give back to your community. We’re the untapped resource,” said Jemain Hunter, the program’s founder. “People are scared because they don’t understand what we’re doing as gun offenders – as far as rehabilitation goes – to come out and not commit these sorts of crimes again.”

“I’m just trying to make sure people don’t end up like me,” he continued.

The program’s first cohort had about 60 participants, and the second, which graduated this August, had double that. The sessions, many of the participants said, allowed them to talk about the shame and regret they feel over their offenses, and connect the dots between the violence they witnessed in their youth and the harm they have caused others.

“It taught me that I was lying to myself for a lot of years,” Sammie Nichols, a 35-year-old graduate of the program’s first cohort, said after the graduation ceremony.

Nichols has been incarcerated since 2008, serving a nearly 150-year sentence. He was transferred to San Quentin in 2023. He grew up in foster care, he said, and started carrying a gun at age 15 after a friend was killed, vowing he wouldn’t meet the same fate.

“Looking back, I did more harm than actually protecting myself,” he said. “I was robbing with it, I was riding with it. I became the offender in every aspect of life. This gun was my power, it was like my authority.”

In addition to its growing popularity among San Quentin’s population, Arms Down has caught the attention of the California governor’s office and prosecutors throughout the state. It’s a success story that Hunter and the men who built the program with him hope can add to the gun-violence prevention work happening on the outside. It’s work that in recent months has been severely defunded by the Trump administration, which cut more than $150m in grants from violence-prevention groups working in underserved, primarily Black and Latino communities.

Hunter has seen people use guns to settle conflicts since he was a kid. He was raised in Fresno, California, and witnessed his first shooting before kindergarten: it was a domestic dispute between his grandparents who, one day, took to opposite sides of their home and began firing at each other. After that, he would regularly see people in and outside of his family pull out firearms during arguments, and regularly heard stories about people being killed after verbal disputes and fistfights.

“It was normal,” Hunter said. “[It was] how to get your way, how to lay down the law.”

As he came into adolescence, toy guns gave way to the real things, Hunter said. When he was 12, he grabbed a family friend’s gun during a fight among his father, his uncle and some other men to get the men off his family. Seeing his willingness to pull out a firearm, older guys in the neighborhood would hand him their guns to hold, and thus began Hunter’s relationship with weapons.

“If someone put this responsibility in my hand and I didn’t do what I was called upon to do, then I would be looked at as a punk or soft,” he said. “I was stepping into that man phase. It’s a whole lot of pressure I put on myself.”

His first arrest was at age 14, after he and some friends tried to rob a gun store in town. Throughout his teen years, he was arrested and incarcerated multiple times, and had gotten into several shootouts, often as the one to pull his gun out first, he said.

Each time he was released, his first thought was how he could get a new gun, he said. The pattern continued until 2002, when Hunter, 24 at the time, would commit his most serious offense: he shot a man after a fight at a gas station. He was convicted for attempted murder, and sentenced to 34 years to life in prison.

In the more than two decades that he has been incarcerated, Hunter has participated in a range of self-help and rehabilitative programs, but found that none of them dealt with the specifics of what he and other Arms Down participants call “firearm addiction”.

Even after years of programming, in the back of Hunter’s mind, he wondered whether people from his past wanted to harm him; he wondered what protection would look like and whether or not a gun factored into it.

“If you’re doing all this time behind this tool and you still feel that you need a firearm after all this, there’s definitely an addiction behind that,” he said.

“All these years, I was co-dependent on a firearm. I always had to know where it was,” Hunter continued. “It was just like your cellphone. You make sure you keep up with it, it’s your life tool.”

With nowhere to talk through those thoughts, he decided to build a space for other men like him.

In late-2023, he began pitching San Quentin’s leadership on a new program, and by February 2024, he and the group’s seven other co-founders and co-creators – all incarcerated in San Quentin – began their first cohort of 60 participants. As word spread about the program, the number of participants doubled and the prison offered them a second day to do their sessions to accommodate the demand.

On Tuesday and Friday evenings, the men meet in the prison’s chapel and, in groups of eight to 12 participants and two co-facilitators, talk about their first interactions with gun violence, when and how they got their first guns and what led up to the events that they are serving sentences for. They range in age from their mid-20 to their 80s.

The weekly meetings, which start with check-ins about the highs and lows of the week, are meant to be safe spaces where people can unpack the traumatic incidents that shaped their belief systems.

This self-reflection allows the men to get clarity on why they picked up a firearm to harm someone or take a life, said Jessie Milo, a program co-creator. “It’s not a place of blame or shame, it’s to unpack and share. Once they start sharing, the circle comes to life,” he said of the weekly sessions.

Milo, 45, has been incarcerated for more than 20 years, and is using his experience of decades in cognitive behavioral therapy, participation in victim impact groups and self-help programs to inform the curriculum for the program, he said.

In watching men of varying ages and races come together to analyze the violence, heartbreak and poor choices that have shaped their lives, he sees pieces of his own story told on repeat.

“I see that same pain in the face of my students when they would tell their stories. It’s a humbling experience. This is my role in helping to stop that cycle,” Milo said.

He grew up in southern California, between Riverside and Moreno Valley, in the 1980s and 90s. Gun violence was ever-present in the background of his childhood and adolescence, he said.

When he was six, his uncle was shot in front of his grandmother’s home while he was inside. And when he was old enough to hang out with friends and go to parties, shootings felt like an inevitability. “That was regular life,” he said.

Milo, cherubic-faced and energetic, doesn’t remember any of the adults in his family asking whether he was OK after witnessing the shootings, or after seeing his mother stabbed during a domestic violence incident when he was eight.

“That would have required another layer of sensitivity to childhood trauma that didn’t exist in the 80s,” Milo said. “Or if it did – it wasn’t in my community.”

He was arrested for the first time at age 14 and spent three years in a boy’s ranch in Yucaipa, a small city about half an hour north-east of Riverside. By the time he returned home, one of his cousins, a good friend and several of his peers had been shot dead.

The camp provided structure, Milo said, but it didn’t teach him how to cope with all the violent losses of his adolescence and the violence he witnessed as a child. Once he got out, he tried working at a lumberyard, hoping to regain some stability before the birth of his son. He ended up hanging around with the same crowd and was in and out of incarceration until October 2002, when a near-car accident escalated into a shooting.

Milo, 22 at the time, was convicted of pre-meditated attempted murder and sentenced to 174 years in prison with several sentencing enhancements for using a firearm and a prior offense. Because of the prior conviction, he is ineligible for any of the state’s sentencing reforms.

“I was sent to die. I was told that the world was better off without Jessie Milo so I was in a constant struggle to prove them wrong,” he said.

Despite having no opportunity to get out of prison, Milo says he’s trying to do his part to stop the cycle of violence in the outside world.

“It’s about legacy. I’m gonna die in a cell and I had to ask myself what I wanted to be remembered for when I leave this earth,” Milo continued. “Someone who brought pain or someone who brought love and healing?

While it’s unclear how many people incarcerated in any California prison are inside for gun crimes, in 2023 25% of the state’s prison population were serving sentences for homicide, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. And according to California’s department of justice, 73% of the homicides in the state that year were committed with a gun. When you add in other common gun offenses like attempted murder, felony possession and assault with a deadly weapon, that constitutes a significant segment of the state’s prison population whose specific needs are going unaddressed, said Demond Lewis, a recent Arms Down graduate.

“You have so many people in prison for committing crimes where they use firearms but there was no setting for you to talk about it,” said Lewis, who’s been incarcerated since 2002 for an attempted murder conviction.

He grew up between Riverside and Perris, a small city about 70 miles (113km) south-east of Los Angeles, in the 1980s and 90s, at the height of the crack-cocaine epidemic. He started selling drugs and carrying a gun when he was 12. “I never thought I had an alternative,” he continued.”I thought of [guns] as a safety measure.”

“When it comes to your emotions as a boy, you’re told you’re not supposed to feel. Once you’re taught that, you go with the secondary emotion, which is anger,” Lewis added. “When you feel sad, you replace it with anger. When you feel confused, you replace it with anger.”

These revelations are the byproduct of his time in Arms Down and his new understanding of the emotions and childhood traumas that contributed to his relationship with guns. Now, he hopes these insights can reach other incarcerated people, like his 30-year-old daughter, who is also in prison for a gun offense. “It was like, her choices were limited based on my actions. I set a pattern for her to follow. Which I had no idea I was doing,” he said.

“We don’t pay attention to anxiety, depression and the stress level of kids. … And this program teaches things like how to do check-ins with yourself. I don’t think there’s an age limit to teach kids that.”

Most of the men in the program are middle-aged and Black and Latino, so when 26-year-old Austin Hogan started attending Arms Down sessions earlier this year, he was nervous to share the details of his crime, in which he and another man shot and killed two Black men during a robbery attempt, for fear of being ostracized by his newfound community of mostly Black youth offenders with whom he was taking classes and doing programs.

“I was finally around people who understood me. I didn’t want all of that to change. I don’t want to have that stigma,” said Hogan, a thin, young blond man with colorful tattoos on his forearms.

Hogan says he didn’t grow up with the same ever-present threat of gun violence like Lewis, Milo and Hunter did. Rather, he grew up with a father who was in the military and taught him the importance of gun safety and the serious weight and responsibility that owning a gun holds.

He came from a lower-middle-class family in Oroville, a small northern California city, and only saw gun violence through movies like Scarface, he recalls. As a teenager, he abused Xanax and began selling weed so he could get the things – like nicer clothes and a BMX bike – that his family couldn’t afford. He started carrying a .357 Magnum revolver after he began selling weed.

“I wanted to party with my friends, make easy money and live that life. I was hypnotized by it,” Hogan said.

He was arrested in the shooting death of two brothers in October 2020 and after four years in jail was sentenced to 30 years to life and sent to San Quentin, classified as a youth offender; he signed up for Arms Down after a fellow youth offender mentioned it to him. Participating in Arms Down has allowed him to unpack baggage he didn’t know he was carrying and confront his beliefs about guns and how they had been shaped by cultural influences like television and video games.

“I saw how people were able to control everything and say: ‘It’s gonna be my way because I have a gun,’” Hogan said. “[Arms Down has] been very educational and enlightening. I didn’t understand that I could be addicted to firearms and the lifestyle of toting guns, that gangster lifestyle.”

Arms Down’s creation and rise hasn’t happened in a vacuum. San Quentin has long been the flagship institution within California’s prison system, with arts, athletics, education and media programming, including a media center where the lauded Ear Hustle podcast was born. In 2023, California governor Gavin Newsom announced the state’s oldest prison would transform into a center for rehabilitation, education and training, modeled after Norwegian incarceration systems. Now called San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, the facility has become synonymous with innovative programming and a shift from prison being used solely to punish.

Since its inaugural class of 2024, word about Arms Down has spread to other California prisons, which Hunter hopes can introduce other incarcerated people to a new way of thinking about their crimes.

Arms Down has grand plans. They’re preparing for their third cohort, which will have 120 participants, with an 80-person waitlist and new sign-ups coming in daily. With support from Sunset Youth Services, a San Francisco-based non-profit that helps youth who have been incarcerated – and their families – navigate the legal system, the organizers are working to get the curriculum formalized and copyrighted so it can be adapted for women’s prisons and youth facilities without losing its central tenets.

The group is also hoping to make the curriculum available to teens and young adults who are on probation or in court-ordered diversion courses for lower-level gun offenses like unlawful possession, in an effort to intervene before their carrying escalates to shooting.

“We want to stop them from going down the same road, especially these kids,” Hunter said.

“We can be the solution if we can take this program and get it in communities before kids pick up a gun to harm someone,” Milo echoed. “Ideally, we’ll have Arms Down mentors who can go into communities and work with the at-risk youth. That’s where we would see the biggest impact.”

This thinking lines up with the state’s recent approach to gun-violence prevention, which includes consistent funding for cities, counties and non-profits through the California Violence Intervention and Prevention Program (CalVIP). It also coincides with what a growing chorus of violence prevention and youth development advocates are lobbying for: programs that can stop teens and young adults who are in and out of incarceration on minor gun offenses from committing more serious, violent felonies.

These programs, a mounting body of research points to, show the most promise when administered by community-based groups that can work in concert with agencies like probation and district attorney’s offices to offer alternatives to incarceration.

“It’s being requested in prisons all over, and there’s community interest,” said Dawn Stueckle, executive director of Sunset Youth Services. “We’re interested in protecting the guys who created it and avoid it getting co-opted and consequently watered down.”

Stueckle and her husband have attended the majority of Arms Down’s Friday evening sessions. In listening to the men tell their stories, Stueckle says, she sees the stories of the young people who have come through the doors of her non-profit over the more than 30 years it’s been in existence. She even ran into a young man who was in a Sunset Youth Services music program, run inside San Francisco’s juvenile hall, as a teen and is now a graduate of Arms Down.

“The conversations parallel what these young people who are gun offenders in the community say,” Stueckle added. “So, how do we take this and adapt it and create something that is as powerful and meaningful to a 16-year-old?”

Arms Down’s leaders have also built relationships with officials like the San Francisco district attorney Brooke Jenkins, who said she would like to see the program reach teens and young adults who are being caught with guns but may not have shot someone yet.

“I do think there is a version of [Arms Down] that can be replicated into our schools and non-profits, because it’s an issue that we’ve got to confront,” Jenkins, who spoke at the graduation ceremony and has attended Arms Down sessions in the past, told the Guardian. “How can we use this curriculum outside of an incarcerated setting? Young folks charged with simple gun possession – to get in front of that cycle before they get an attempted murder charge.”

“Arms Down has provided a class not previously seen to address the addiction to guns and power,” Chance Andes, San Quentin’s warden, told the Guardian in an emailed statement. “It provides a platform to understand where the need to carry and use guns came from. From inside prison, Arms Down is a vital program for those who committed crimes using guns. For outside the walls it is an additional tool to public safety.”

At the graduation, after the speeches, a panel discussion – comprising Arms Down participants, Jenkins and a representative from the California governor’s office – and poetry recitation, the men in the cohort walked to the chapel’s stage one by one, and received a certificate and hug from one of Arms Down’s co-founders.

By the end of the ceremony, Hunter was “running on fumes”, but he was happy to see the men graduate, and the moment fueled his excitement about the program’s future.

“We leave a narrative behind when we commit these crimes,” Hunter said. “But wouldn’t it be awesome to have someone come back out and tell you: ‘Naw, this is why I did this and this is why you shouldn’t.’”

“This is something that’s healing for me. That makes me feel whole,” he continued.

3 months ago

38

3 months ago

38