For a quarter century, In the Mood for Love has remained one of cinema’s most romantic texts; it only makes sense that audiences swooned when Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art programmed the Wong Kar-wai film at its Australian Cinémathèque in late 2025. Two sessions in the venue’s 220-seat main cinema sold out swiftly. A third session was added at short notice on a night the 20-year-old site isn’t usually open, and neared capacity, teeming with eager viewers.

And not just classic cinephiles, either. The film, says Amanda Slack-Smith, Australian Cinémathèque’s longstanding curatorial manager, “got out to a lot of communities. We’re seeing a lot of intergenerational families coming in – older parents with their 50-year-old kids, and they’re bringing their kids.”

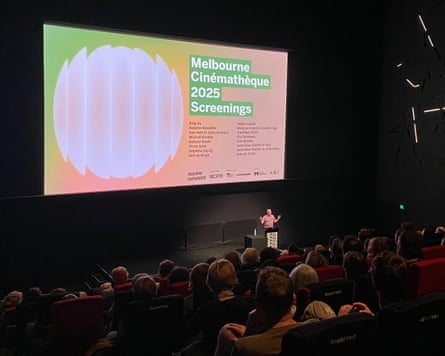

Pioneered in Paris in the 1930s as a means to preserve celluloid archives, the cinematheque champions movies as an artform. Fittingly, Australia’s three biggest reside in galleries and museums: the one at Goma, Art Gallery of New South Wales’s soon-to-launch Sydney Cinémathèque, and Melbourne Cinémathèque at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. In Adelaide, there’s a cinematheque at the arthouse Mercury cinema; in Western Australia there is Perth’s Revival House; and the Hobart Film Society, which has been kicking since 1946, still hosts weekly screenings for members.

Each appreciates cinema as a window to and vital record of the world, across retrospective screenings, underseen highlights and indie discoveries. At a time when it can feel as if everything is available everywhere all at once, cinematheques are an alternative to the Hollywood franchise churn at multiplexes and streaming’s endless scroll. Patrons, especially new attendees from younger demographics, are valuing that approach and even altering their viewing habits accordingly.

Slack-Smith believes a cinematheque’s task is providing avenues for discovery. “But it’s not about shoving scholarship down people’s throats,” she says. “It’s about us being translators, I think. We put on our Indiana Jones hat, we go out there, we find all the gems, we bring them back.”

Commercial theatres can seldom fulfil that role, even with year-round retrospective programming often on their schedules. The film industry data firm Gower Street Analytics reported a global box office last year of US$33.55bn – or, in other words, still struggling to match pre-Covid figures. “They’re a business, they have to survive,” notes Slack-Smith. “So if it wasn’t for places like cinematheques, how do you have those conversations? How do you see that material? And how do you put it in context?”

When Australian Cinémathèque programmed In the Mood for Love, for instance, it was part of an ode to Hong Kong star Maggie Cheung, while other notable recent seasons have showcased Japanese film-maker and Drive My Car Oscar-winner Ryusuke Hamaguchi as well as the work of Charles Burnett, director of the widely revered class drama Killer of Sheep.

Sydney Cinémathèque begins welcoming audiences from March, rebranding and expanding AGNSW’s screening program that dates back to 2000. As film curator Ruby Arrowsmith-Todd explains, one of its aims is aligning with the gallery’s existing cinema audience, which is “increasingly much younger” and “a lot more diverse” since Covid.

In Melbourne, Grace Boschetti fits the next-gen mould, embracing Melbourne Cinémathèque upon seeing Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse while at university. She became an annual member in 2022 and has been volunteering on the organisation’s committee since 2025.

Her first visit was “a really transformative experience”, and soon she was attending repertory screenings approximately four nights a week. Beforehand, Boschetti was seeing majority new releases, she says. “Now, I see maybe a new release every two to three weeks and everything else is retrospective screenings.”

Australia’s cinematheques fulfil a much-needed role, then: an antidote to streaming and the false sense of abundance provided by digital platforms despite favouring recent and English-language titles. Streamers haven’t threatened Boschetti’s fondness for the silver screen; for her, as for many of Australia’s cinematheque obsessives lapping up expertly curated double features week in and week out, “it’s never the ideal way to watch something, at home. Watching something in a cinema is always going to be a better experience.”

Arrowsmith-Todd also attributes the rising number of young attendees to “platforms like Letterboxd” – the film-focused social media app that now has 17 million members and an outsized presence on red carpets. “Each year there’s a new cohort of young people coming through, keen to see the so-called classics but also increasingly voracious for films that are far off the typical canon list,” says Arrowsmith-Todd.

Arrowsmith-Todd sees Sydney Cinémathèque as an opportunity for emerging film professionals as well, such as critics, programmers and – crucially – projectionists. There’ll be “more training behind the scenes”, she says, in analogue projection, allowing the gallery to “screen the full film history from 35mm, 16mm, all the way through to the present”.

The days of a new-release movie flickering through projectors on celluloid are long gone at most commercial cinemas. When a title does screen on film, it is now touted as a special event; select 70mm sessions of Marty Supreme recently played in Sydney and Melbourne, for example. It’s another gap that cinematheques are filling, with the format of their movies almost as crucial as the features themselves.

In the Mood for Love screened at Goma in its original cut on 35mm. The audience, says Slack-Smith, knows “the difference between the director’s recut and recolourisation, and the original film on print … There’s still a lot of real interest and love for the original.”

That interest – that curiosity – feels central to the enduring success of Australia’s cinematheques. “If you start attending retrospective screenings and particularly cinematheque screenings on a regular basis, you are going to learn so much about film that you didn’t know,” Boschetti says.

“There’s just a particular magic about a lot of these films that I don’t think I get out of new-release films. I see something and it’s the best thing I’ve ever seen – it’s very rare for me to see a new-release film that amazes me in the same way.”

4 weeks ago

31

4 weeks ago

31