Bandra, Mumbai, 1998.

Andrew Rogers, a 34-year-old Sydney greenkeeper, was visiting family in India with his wife, Winnie, and one-year-old son, Terence. Inside, as aunties prepared breakfast – the kitchen a sanctuary from the humid, honking streets – the phone rang.

“Don’t answer it,” one auntie warned. “We’re about to go shopping.”

But Winnie insisted he pick up – she had intel.

“Hey, is this Andrew Rogers?” a gravelly Australian voice asked. “You’ve won a trip to see the Titanic.”

Winnie nodded enthusiastically but Rogers assumed it was an elaborate prank. “I didn’t believe it,” he recalls now. “I thought I’d won tickets to the Titanic movie.”

The surreal news was the result of a supermarket run: before leaving Sydney, Winnie had stocked up on treats at a local Franklins, where every $10 spent earned an entry into an unconventional competition. In a draw from 270,000 entries at Manly’s now-defunct Marineland, Rogers took the $65,000 prize: a seat on the first commercial expedition to the wreck, 4km below the ocean’s surface.

A joint venture between the entrepreneur Mike McDowell and Moscow’s Shirshov Institute, the mission used the research vessel Akademik Mstislav Keldysh and its twin submersibles, Mir-1 and Mir-2.

For a man more accustomed to Sydney’s northern beaches than the abyss, a life-altering journey was beginning in a time before extreme tourism, before private deep-sea exploration – he was a rare civilian entering a void that felt more like science fiction than a holiday.

The family flew to Toronto, where Andrew continued solo to St John’s, Newfoundland – off Canada’s Atlantic coast – via Halifax. Early the next morning he boarded his home for the next 11 nights, the 125-metre Russian research vessel which would take him to the wreck, which claimed 1,522 lives in 1912 and was rediscovered in 1985.

Among the 16 ticket holders – mostly high-paying clients – were the crew, deep-ocean researchers, and experts including the Halifax marine geologist Alan Ruffman, who wrote a book about the Titanic. Rogers befriended Gregoreya, the Ukrainian leader of the deck crew, who was fascinated that he was all the way from Australia.

They built rapport, sharing smiles and a few English words. Gregoreya always had a knife in hand, whittling away at a piece of wood, while Rogers spent days watching the “cowboy” – a diver – plunge from a dinghy into the freezing, choppy water to tether subs with rope so they could be hoisted aboard.

And then it was Rogers’ turn, his descent delayed until nightfall by heavy swells – ahead lay a 4,000-metre drop into 6,000 PSI of pressure, in which a single crack meant instant death.

After securing a foam plaque for his son – “To Terence, from the Titanic” – to the basket on the front of the sub, he squeezed into the two-metre-diameter vessel with its pilot, Genya Chernaiev, and a co-passenger, Roman Sugden – a California undertaker whose boss had given him the ticket.

The crane latched on to the sub, lowering them into the Atlantic.

Inside the steel sphere, camcorder at the ready, Rogers watched the water change from navy blue to complete darkness. In the freezing, cramped space, he and Sugden lay on their stomachs, legs curled, peering through thick glass portholes.

Down they went for two and a half hours, the vast blackness dotted by a handful of fish and prawns.

“We were excited,” Rogers now says. “I was asking Genya questions and constantly looking out through the tiny porthole … [I had] no apprehensions at all.”

He learned they were in the same submersible the film-maker James Cameron used to research his film – Chernaiev says the director furiously took notes for the entire trip.

“As we got close to the bottom, Genya told us we were near the stern of the ship,” Rogers says.

Chatter ceased as the floodlights caught the muddy ocean floor. “I can’t put it into words,” he says. “There was nothing, and then you just see the Titanic, crystal clear.”

A colossal propeller emerged from the darkness.

The ship lay split, driven 12 metres into the silt.

“I was pretty overwhelmed, almost tearing up and not really knowing how to deal with the emotion,” Rogers says.

Peering through his small window, he saw a crab perched on a rusticle – an icicle-like structure made by iron-eating bacteria.

His home video captured the mangled rails made famous by the film’s “king of the world” scene, where rust now “runs down like a river”.

Along the walls, the White Star Line logo remained emblazoned, and flecks of white paint still clung to the steel.

The pilot manoeuvred through jutting beams where a snag could be fatal. As they passed the bridge, they saw Captain Smith’s enamel bathtub, frozen in time.

They paused for lunch beside the wreckage: sandwiches, with tea from a vacuum flask.

Nearby lay beaded and brass fragments of chandeliers. Then, drifting closer to the seabed, they saw a single boot among shards of rotting timber, plates and pans – a sobering reminder of the tragedy’s human cost.

“To travel down in dark nothingness and see a sign of human life … the whole thing was mind-blowing,” Rogers says.

Before the five-hour exploration ended, they persuaded the pilot to use a robotic arm and its iron claw to collect a rock from the ocean floor next to the shipwreck.

Then it was time to leave, reluctantly, before their oxygen ran out.

They rose back into the abyss like a spacecraft departing a lonely planet. Sugden slept during the three-hour ascent but Rogers was too exhilarated to close his eyes.

After 11 hours they emerged into the fresh air. Rogers found his foam sign shrivelled to a fraction of its size – a relic of the crushing depths.

There were no official souvenirs on board but the parting gifts were better. Chernaiev cracked the seabed rock in two, giving Rogers a jagged half.

Gregoreya came to say goodbye and presented him with his finished whittling project: a fish scaler.

It was inscribed: KELDYSH, MIR I & II, ANDREW ROGERS – AUSTRALIA. KANADA = TITANIK = 1998. In return, Rogers gave him an Australian T-shirt.

Back in Sydney, the greenkeeper says the “almost otherworldly” experience led him to see the world through a new lens. “I think about it very often,” he says. “The word Titanic is part of our language now, so I’m reminded every time I hear it.”

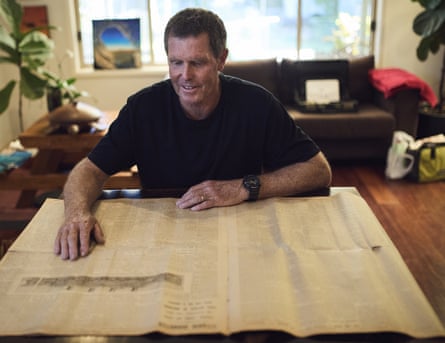

And his connection sparked a new obsession. He has newspaper clippings about the disaster and a framed picture of the ship adorning a wall at home.

He started scouring microfilm for Australian Titanic survivors, leading him to discover Evelyn James (née Marsden), who had escaped in a lifeboat.

“I was obsessed with finding Evelyn’s grave,” he says. “I knew it existed and wanted to see what epitaph might be on any memorial stone,” he says.

Instead, he found an unmarked grave at Waverley cemetery in Sydney’s eastern beaches.

It’s not known why she didn’t have a tombstone but Rogers was “excited at the thought of having a job to do” and arranged for one to be erected in her honour.

Twenty-seven years later, Rogers says he rarely tells people about his extraordinary adventure now because “they don’t believe me” – but it’s never far from this thoughts.

“I’ve experienced a whole other dimension in life,” he says, “and a further appreciation of how amazing the world – and beyond – is.”

1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31