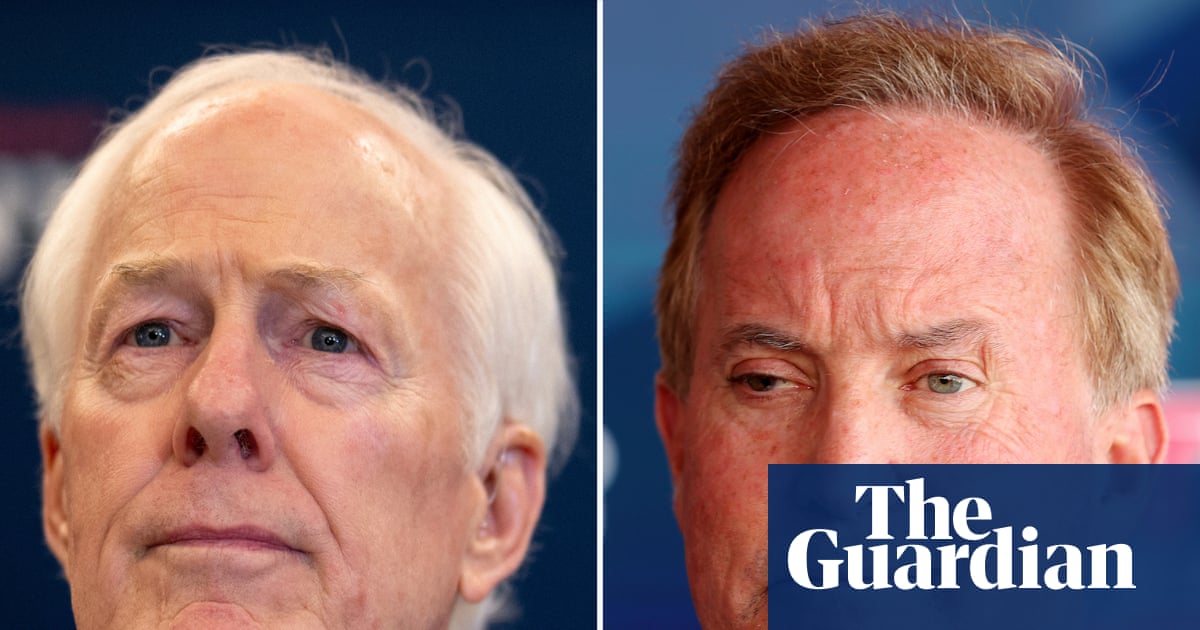

One month ago, a White House meeting between Donald Trump and his Colombian counterpart, Gustavo Petro, would have been unthinkable.

The US raid on Caracas to capture the Venezuelan leader, Nicolás Maduro, brought already heated relations between them to a boil, with Trump warning the leftist Colombian leader “could be next”, claiming Petro was a “sick man who likes making cocaine and selling it to the United States”.

Petro, a former guerrilla who demobilised in the 1990s, responded defiantly: “I swore not to touch a weapon again … but for the homeland I will.”

Then, a 7 January phone call, frantically coordinated by diplomats in both countries, put the brakes on the fiery tit-for-tat and ended with Trump’s invitation to Tuesday’s meeting in the Oval Office.

What may come of the encounter is uncertain.

“It’s hard to predict because you’re dealing with two very erratic, temperamental presidents,” said Michael Shifter, an expert on Latin American geopolitics and professor at Georgetown University. “They could be their usual controversial confrontational selves. That wouldn’t shock anybody, though; they are in the mood for detente.”

Victor Mijares, a political science professor at Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes, said a lot would depend on whether Petro arrives at the White House prioritising his personal agenda over a national one.

“He has a two-pronged agenda,” said Mijares.

On the national front, problems of drug trafficking, regional security, trade and migration top the list. Petro’s personal agenda includes giving Trump reassurances that he is, in fact, neither directly nor indirectly involved in his country’s narco-trafficking as the US president has suggested publicly, without evidence.

Even so, in October, the US slapped Petro, his wife and the interior minister, Armando Benedetti, with sanctions for what the treasury department claimed was “their involvement in the global illicit drug trade”.

It also revoked his visa after Petro stood on a New York street, megaphone in hand, addressing a pro-Palestine rally and called on American soldiers to disobey any illegal orders from their commanders.

“I’m afraid that if Petro is true to his nature, he will give priority to his own interests,” said Mijares. The fact that the US lawyer who Petro hired to challenge the sanctions, Dan Kovalik, was among the team in preparatory meetings in Bogotá last week, indicates they are a top concern for the Colombian president.

“It is a key meeting, fundamental and decisive, not only in my personal life but in the life of humanity,” Petro said in a speech last week.

During the same address, and after weeks of near silence, however, he returned to criticising the US for the capture of Maduro, saying that the United States should return the Venezuelan leader who has been charged with multiple US federal crimes, including facilitating drug trafficking through Venezuela, to stand trial in his own country.

However, in the weeks between the phone call between the two presidents and the face-to-face meeting, Colombia has quietly shown a willingness to appease the United States.

The government has announced it will soon restart the aerial spraying of coca crops with the herbicide glyphosate. US-backed spraying from crop dusters was a central part of the billion-dollar Plan Colombia strategy to fight drug trafficking in the early 2000s but was suspended in 2015 over health concerns. Since then, estimated cocaine production in Colombia hit record levels in 2024, according to UN monitors.

Petro has also announced last week the restarting of migrant deportation flights to Colombia, the original trigger of the Petro-Trump conflict in January 2025, days after Trump took office.

The two countries could also find common ground in acting jointly against the National Liberation Army (ELN) – Colombia’s largest guerrilla group – near the Venezuela border, after failed peace talks.

“Colombia could be a helpful actor in Venezuela,” said Benjamin Gedan, director of the Stimson Center Latin America program. “And Colombia would benefit tremendously from a more stable and prosperous neighbour.”

But, he warned: “It isn’t clear Trump recognises those regional dynamics. Indeed, Trump generally underestimates the importance of Colombia.”

Petro, whose term ends on 7 August and cannot run for re-election, will not only be staking much of his legacy on this meeting, but it could also be decisive in the upcoming presidential elections in May.

The mere fact the meeting is happening will help the campaign of Iván Cepeda, a leftist ally of Petro who hopes to continue his political project. “It will throw the [rightwing] opposition off a bit,” said Shifter.

Mijares agreed: “It’s bad news for the right in Colombia if the meeting goes well.”

4 weeks ago

31

4 weeks ago

31