On a bitterly cold recent morning in the Canadian Arctic, about 70 people took to the streets. Braving the bone-chilling winds, they marched through the Inuit-governed territory of Nunavut, waving signs that read: “We stand with Greenland” and “Greenland is a partner, not a purchase.”

It was a glimpse of how, for Indigenous peoples across the Arctic, the battle over Greenland has become a wider reckoning, seemingly pitting the long-fought battle to assert their rights against a global push for power.

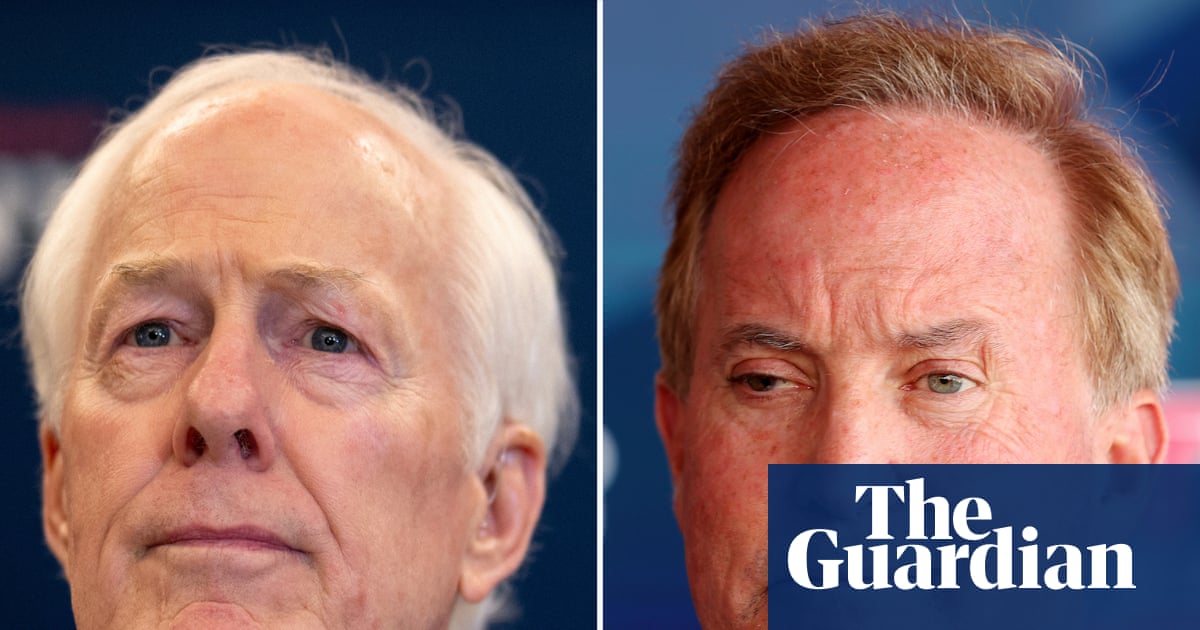

Donald Trump’s tug-of-war over Greenland recalled “centuries of imperialism by different nation states but also colonisation by different actors”, said Natan Obed, the president of Canada’s national Inuit organisation, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

“Inuit have had to figure out how to maintain our society, our culture and our self-determination in the midst of other people wanting different things from us or from our lands and territories.”

It was a past many thought they had left behind. “The overtures from the United States – and it isn’t just one individual but a chorus of individuals all saying very similar things – makes us incredibly worried that we are on the precipice of another age of disrespect for our collective rights,” said Obed.

Particularly concerning was the focus on Greenland’s efforts to extract mineral wealth or create defence positions, said Obed. “That’s the scariest part of the rhetoric that has been circulating,” he said. “I did believe we were beyond this central premise that if Indigenous peoples do not improve our land based on the criteria of imperialist actors, that somehow we do not have self-determination. The decisions that are made about our land and what we want for it are ours alone.”

While Trump recently pledged that he would not take Greenland by force, the White House has signalled that it remains keen to control the world’s largest island. Jeff Landry, the US special envoy to Greenland, penned an op-ed describing Greenland as “one of the world’s most strategically consequential regions”.

The 976-word piece, published in the New York Times, made no mention of the Indigenous people who had stewarded the land for millennia, noting instead: “The president has been unequivocal: American dominance in the Arctic is non-negotiable.”

In Greenland, residents have described Trump’s statements about “buying” or “taking over” the territory as a return to a time when Indigenous lands were seen solely as commodities to be acquired, leaving Inuit sidelined from the political negotiations that shaped their lives.

“In the increased tension between great powers, our concern is that the Arctic is portrayed as an asset or as an empty ice desert,” said Sara Olsvig, chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council and a former leader of Inuit Ataqatigiit, a leftwing pro-independence political party in Greenland. “To us it is our homeland, its riches are what sustain our people, our culture, our children, youth, and elders. Inuit have lived and thrived in our Arctic region for time immemorial, long before the concept of states.”

The push for power had laid bare how many had failed to recognise that after centuries of rule under Denmark, Greenland was now a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark. “Thus, Greenland is not ‘owned’ by Denmark, nor can Denmark ’sell’ Greenland,” Olsvig said in a statement.

The past months had been laced with “connotations to earlier times of colonisation”, she said, forcing her and others to stress that Inuit and the people of Greenland were equal to all others.

“Not repeating the wrongdoings of past imperialism is important,” she said, adding: “There is no such thing as a better coloniser.”

As Trump’s rhetoric intensified, Inuit in Alaska had followed the situation closely. Marie Greene, the president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council – Alaska, said: “At first it was unbelievable, then it became heartbreaking as we heard about our people, especially kids and elders, worrying about being invaded.”

The threats were a sharp blow to Inuit who had long worked together to ensure that the Arctic remained a zone of peace, even as tensions simmered among the world powers that surround it. “For Inuit, peace in the Arctic is not an abstract principle; it is about protecting our homelands, our families, and the future of our children,” said Vivian Korthuis, also of the Inuit Circumpolar Council – Alaska. “Lasting peace comes from listening to Inuit, respecting our rights, and engaging with us as partners whose knowledge and responsibility are rooted in the Arctic itself.”

The conversation over Greenland had reinforced how Indigenous peoples are uniquely vulnerable to geopolitical turbulence, said Gunn-Britt Retter of the Saami Council, an organisation representing the Sámi peoples of Finland, Russia, Norway and Sweden.

“When geopolitics gets heated, you get into this mode where state leaders start talking and the first thing that is forgotten is Indigenous peoples,” said Retter. “There’s always something more important. It’s like: ‘Yeah we value Indigenous peoples or we respect the rights of Indigenous peoples, but right now this is more important.”

The sense was that Indigenous rights were something to be held up in good times, only to be overridden when strategic interests, such as the threat of tariffs, come up, said Retter. “Indigenous issues become something to talk about when there are budget surpluses.”

For many in the Arctic, it was hard not to see the threats looming over Greenland as a sign of what was to come, said Obed of Canada’s Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. “We understand that we are increasingly in the centre of a geopolitical fight that is not necessarily around our culture or our society, but is in our homeland, in our backyards,” he said.

He pointed to the vast funds that both Russia and China had poured into bolstering ports in and around the Russian Arctic and the quiet scramble to claim the Northwest Passage as climate change transforms the region as examples.

“We know these fights are coming,” said Obed. “So this is the moment to build alliances and strategies and plans to ensure that when those times come, we’re ready for that.”

4 weeks ago

34

4 weeks ago

34