A cluster of serrated concrete bunkers has landed in the heart of Princeton University’s leafy campus in New Jersey, sending tremors through this twee Oxbridge fantasyland of gothic turrets and twiddly spires. The new addition’s brute, blank facade gives little away from the outside. Wrapped in rows of vertical grey ribs, contrasting with the arched windows of the surrounding stately stone halls, it has the look of a secure storage facility, keeping a beady eye out through a single cyclopean window.

The vault-like quality is fitting. This bulky new bastion is a repository for the university’s astonishing collection of art and antiquities – a 117,000-strong haul spanning everything from Etruscan urns and medieval staircases to expressionist paintings and contemporary sculpture. Previously housed in a hodgepodge of extensions and additions accrued over decades, the collection can now shine in its own purpose-built castle.

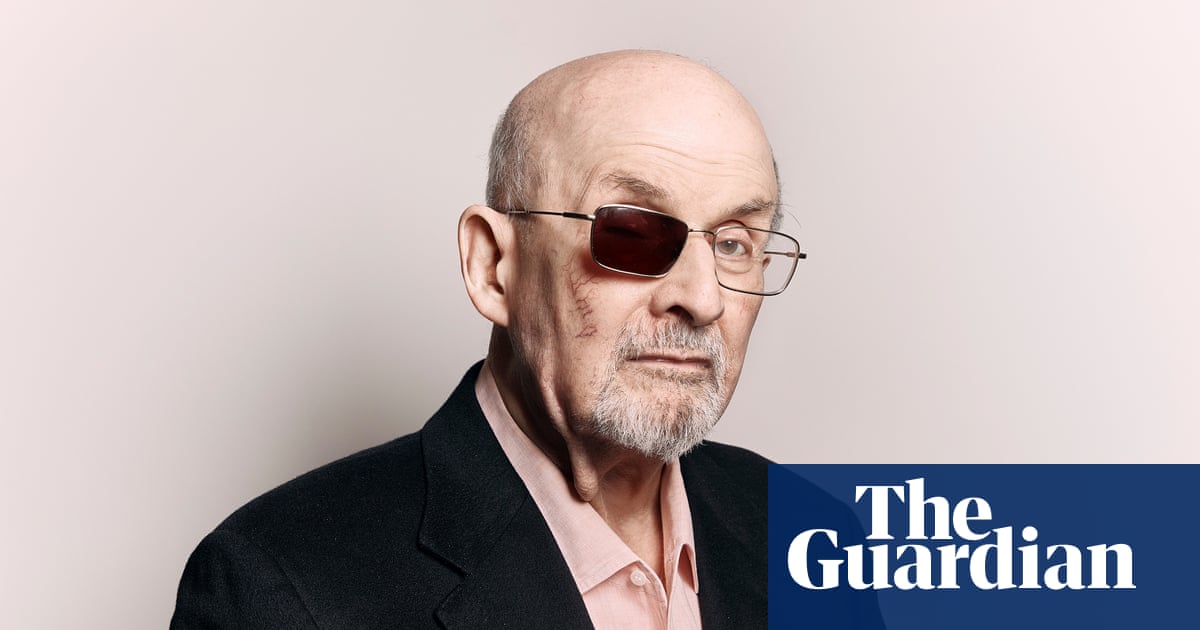

The building might need its thick skin – and not just to deter Louvre heist copycats. The Princeton University Art Museum is the first major project by the Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye to open since 2023, when three women accused him of sexual assault and harassment. Adjaye has denied the allegations and no charges were brought against him, but the scandal saw his meteoric rise swiftly turn into a dramatic fall from grace. Numerous projects around the world were cancelled. But Princeton pressed on.

“We were about 60% complete,” says museum director James Steward. “So we couldn’t exactly tear the building down.” Instead, the university distanced itself from Adjaye Associates and handed over day-to-day coordination to Cooper Robertson, museum specialist architects, who had been intimately involved since the beginning. Adjaye has not been on site and has not been invited to the opening – which, in a ghoulish turn, will take place on Halloween.

The allegations cast a cloud over what is one of the finest art museums to be built anywhere in recent years. For once, the absence of a celebrity creator allows attention to fall on those who led the project after Adjaye stepped back – chiefly Marc McQuade, former associate principal at Adjaye; Erin Flynn, partner at Cooper Robertson; and Ron McCoy, Princeton’s in-house architect. Together they have conjured a place of rare substance and craft that revels in its theatrical spatial effects and sensuous material details, standing at the historic centre of Princeton’s campus with a timeless air.

As you approach the complex, which is partly hunkered down in a hollow, the blunt facades of the nine raised gallery pavilions seem to soften at ground level, with terraces and ramps leading you into the museum on all four sides. The principal entrance, beneath a low overhang, opens into a dramatic four-storey space, where a colossal mosaic figure by the artist Nick Cave leans forward in a riotous gesture of welcome. Passing through this pharaonic canyon, visitors reach a lower, darker entrance space, before reaching a lofty welcome gallery where daylight floods in through upper windows, and a grand staircase beckons to the galleries, mirroring a 15th-century limestone staircase from Mallorca, displayed on the wall opposite.

“We wanted it to feel like an open thoroughfare,” says chief curator Juliana Ochs Dweck, standing at the crossing of two routes that slice through the building, north-south and east-west, following the line of pre-existing paths across the campus. “If the students happen to see a couple of works on their way through, and get interested in the arts, that’s a bonus.”

Beneath her feet, protected by a glass floor, is a third-century Roman mosaic pavement. Excavated from a site near Antioch in the 1930s by a team of Princeton archaeologists, it depicts a drinking contest that could be straight from the student bar. Nearby hangs a vibrant pink and green abstraction by the great minimalist Frank Stella, painted the year he graduated.

Continuing along “the artwalk”, you come to the grand hall, a triple-height space where hefty concrete buttresses jut out overhead, supporting two-metre-deep wooden glulam beams that frame skylights above. Corner glazing provides tempting views of the ceramics collection that awaits upstairs, while sliding oak panels can close the windows off for events, as retractable seating and a stage cleverly slide out. The space has inescapable echoes of Louis Kahn’s Yale Center for British Art, only beefed up. The sandblasted concrete gives a rugged, geological quality, the sheer size of the structural components lending a brawny heft. There are hints of Ivy League one-upmanship: this is Kahn on weight-gain formula.

Upstairs, the sequence of galleries is brilliantly judged, switching size, height and colour to avoid museum fatigue, and banishing that all too familiar feeling of traipsing through endless indistinguishable white rooms. “This is not a museum that has embraced a white cube display approach since at least the 1980s,” says Steward, who has been director here since 2009, co-curating around 150 exhibitions. “We used colour as a way to grapple with the design flaws of our previous building.”

Each of the 32 galleries has a different hue, ranging from pale greens to deep blues, with some walls upholstered in richly patterned fabrics, echoing the stately drawing rooms where some works once hung. Immaculate display cases designed by Goppion of Milan allow dense groupings of objects to sing, from netsuke sculptures to snuff bottles. Behind the scenes, the mechanics have been cleverly tucked away into the V-shaped wooden beams that span the ceilings, carrying the air-handling and lighting tracks, while daylight is brought in via reflective solar tubes, spreading an even wash across the rooms.

Tucked into the corners of the building, three chapel-like spaces offer visitors a more contemplative encounter with certain works. Entirely lined in timber, with built-in furniture and picture windows framing views back out to the campus, these sequestered rooms provide welcome moments of respite between the nine themed gallery zones. It’s nice to have a sit-down on your travels between Africa, Asia and the ancient Mediterranean via the Americas. While the previous museum had an unfortunate upstairs-downstairs separation, with many visitors never reaching the African and Asian galleries below, the new building puts everything on one level, roughly doubling the display area in the process. With no clear order or hierarchy, the idea is that you wander at will.

“We want people to get productively lost,” says Steward. “The hope is that visitors will have accidental encounters on their way from A to B. We put our temporary exhibition space, and the restaurant, as far from the front door as possible, to force people to encounter different things on the way.”

There are plenty more details to enjoy, from the auditorium with its walls of pink felt-covered ribs, to the chainmail curtains that seal the galleries off after hours (the public areas will be open until 10.45pm every night). Then there are the study rooms and endless seating nooks built into the walls, both inside and out, as well as terracing that extends into the landscape, providing a venue for outdoor events in the warmer months. The impressive quality of construction – particularly unusual in the US – is the product, says McQuade, of endless prototyping and material testing, a testament to the client’s exacting standards and the precision of the contractor, LF Driscoll.

David Adjaye’s institutional work, at scale, has often been disappointing. His Idea Stores in London are flimsy exercises in jollying up public libraries – and they are now showing their age. His National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington DC, sports a dazzling skin, but it is clumsy and underwhelming inside. His Sugar Hill housing in Harlem, New York, similarly prioritises its eye-catching wrapper at the expense of the homes within. As they have grown in size, Adjaye’s projects have all too often given the impression of someone in a hurry.

Whatever caused the Princeton museum to be leagues ahead – perhaps a combination of experienced lead architects, collaborative contractors and a model client – its success is clearly down to much more than one man, whose name still hangs above the office door.

3 months ago

57

3 months ago

57