Communist East Germany’s high-rise prefab residential blocks and their political and cultural impact in what was one of the biggest social housing experiments in history is the focus of a new art exhibition, in which the unspoken challenges of today’s housing crisis loom large.

Wohnkomplex (living complex) Art and Life in Prefabs explores the legacy of the collective experience of millions of East Germans, as well as serving as a poignant reminder that the “housing question”, whether under dictatorship or democracy, is far from being solved.

Fifty works by 22 artists, most of whom lived in or near a plattenbau (literally “slab building”, after the panels from which they were constructed), draw on how the large-scale, standardised developments shaped the lives of their residents and by extension the wider society. Their construction was placed at the heart of the German Democrat Republic dictatorship’s social policy and also largely underpinned its industrial raison d’etre.

“It’s about the ‘slab’ or prefab as a place and memory of living, as a symbol of social utopias and as a canvas for social change,” says Kito Nedo, the curator of the exhibition at the Minsk gallery in Potsdam, itself an important architectural monument of the so-called Ostmodern, which narrowly escaped demolition after local protests.

“The biggest question in the room, more relevant than ever in Germany and cities across Europe, is how to create affordable, quality housing,” Nedo adds. “The housing plan of the GDR was an historic attempt to address this question. It’s one politicians are called on to find an answer to today.”

From the time it went into mass production in the 1970s, a flat in a standardised concrete prefab complex was considered a veritable “des res” by many East Germans, lured by the promise of their own indoor toilet (an IWC), an open-plan kitchen/dining area with a pass-through hatch and reliable district heating, plus the amenities provided in each housing development, such as public transport links, a kaufhalle (department store), childcare facilities, schools, youth clubs and polyclinics, or large health centres. Green areas for leisure were also promised, if sometimes slow to materialise.

The speed with which they were erected is depicted in Sonya Schönberger’s archaeological-style sculptures, which capture in silicone the shoe and paw prints of residents left on the still wet concrete slabs of the Baltic Sea Quarter, built in Berlin-Neu-Hohenschönhausen and Lichtenberg, between 1984 and 1988.

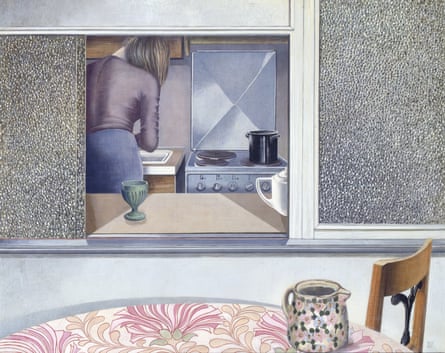

The design of the housing estates – childcare provision, proximity to the workplace – was seen as progressive, and intended to reinforce gender equality, as laid out in the GDR’s constitution, with women and men expected to work, even if, in reality, as referred to in Kurt Dornis’ painting Second Shift, which views a woman through a hatch into the kitchen, many women still ended up, after work, carrying out the bulk of domestic tasks at home.

The standardisation of the flats, and life in general, was reflected in jokes at the time, including how, even when blindfolded, electricians were able to immediately locate the outlets for power sockets.

“East Germans joked about never having to ask where the toilet was if they visited a stranger’s home,” says Nedo, who grew up close to one of the GDR’s largest complexes in Leipzig.

The author and director Grit Lemke describes the strong sense of community that existed growing up in a high-rise complex in Hoyerswerda, designated a socialist model city “where everyone knew everyone else … we kids played plattenhasche (prefab tag) … where I had taken a bath in everyone’s tub … a childhood in a large collective that was wild and free.”

While they were admired by many, because of their lack of comfort and individuality, the prefabs also drew derogatory nicknames, such as Arbeiterschließfächer or workers’ lockers. The writer Heiner Müller, who lived on the 14th floor in a 166 metre sq flat in Berlin-Lichtenberg, mocked them as “fuck cells with district heating”.

Brigitte Reimann, whose critical take on GDR housing is thematised in her 1974 novel Franziska Linkerhand, about an architect whose dreams of creating a city of the future fail due to the strict ideological dictates of the construction rules, called the plattenbau “faceless and interchangeable”, “that hive of dozens of cells stacked next to and on top of each other”.

The exhibition documents these and other observations in paintings, photographs, sculpture and an accompanying programme of readings, films and walking tours.

A series of black and white photographs by Sibylle Bergemann shows how people sought to bring individuality to the grid-like uniformity of their homes through the use of wallpaper, lamps and cuddly toys.

Balkonkultur also developed, whereby residents would pep up their balconies with awnings, decorative antique wagon wheels, brick-patterned linoleum and flower boxes, leading the architectural sociologist Bruno Flierl to comment at the time that the phenomenon was an expression of “anti-authoritarian self-help”, and a “subjective form of architectural critique” by the residents, whose “imagination and courage should be admired”.

As much as it was once sought after, the plattenbau’s image plummeted after the fall of the Berlin Wall, becoming a symbol of social decline. Housing blocks were either demolished en masse, reduced in size as whole storeys were removed, renovated or rebuilt.

Henrike Naumann’s still life installations Amnesia and Terror refer to the radicalisation of the far-right terror cell NSU in prefabs in the city of Jena as well as the series of racist pogroms that took place in cities such as Hoyerswerda and Rostock-Lichtenhagen as the once-new housing developments became places of painful transition.

Places such as Hoyerswerda rapidly shrank as factories closed, people moved away and state-subsidised demolitions took place.

“Now finally the connection between utopia and reality could materialise,” Lemke says. “But it slipped through our fingers.”

Nedo says the exhibition is not about nostalgia but recognising the continuing existence of the plattenbau. “When we talk about the GDR, history stops in 1990,” he says. “Much of the representative architecture has been torn down. But the plattenbau are still there, and so too is the collective experience of living in them. You can still visit them, acknowledge they are part of the present, even if people almost never do.”

3 months ago

49

3 months ago

49