The spectators on the grandstand at Ngong Racecourse in Nairobi jumped to their feet as the horses competing in the fifth race of the Day of Champions – the last meeting of the season – came around the final corner on a recent Sunday afternoon. “Bedford! Bedford! Bedford,” some roared, punching the air as the horse, jockeyed by Michael Fundi, broke into a gallop on the home stretch, passed the leader, and stormed to victory.

Fundi, who had started the day on top of the jockey standings, was crowned the season’s champion after the last race. At 20, he was the youngest in a decade.

-

Above: Michael Fundi with Bedford after winning the 2400m Jockey Club Stakes George Drew Challenge Series.

-

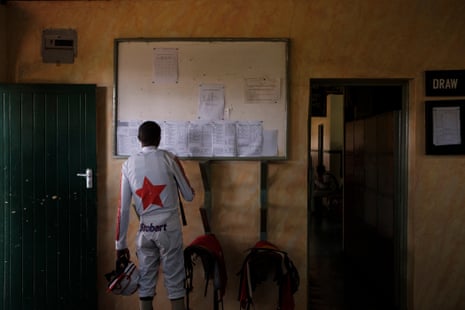

Left: Kenya’s former president Uhuru Kenyatta presents the champion jockey plate to Fundi. Far right: Fundi speaks with former champion James Muhindi (L) in the weighing room before the 1200m Alico Limuru Cup race.

“This is one of those feelings that you can’t put in words,” he beamed in the parade ring after his award presentation.

Fundi embodies the growing involvement of black Kenyans in horse racing, changing perceptions of a sport that has been synonymous with the country’s white minority since the British colonial era.

“Growing up, that was a sport for other people, not me,” said Muturi Mutuota, who, like many other children in Nairobi in the 80s and 90s, was taken to the racetrack by his parents at weekends.

Now, Mutuota, who is in his 40s, is a director at the Jockey Club of Kenya, which operates and regulates the sport. At this year’s Day of Champions, three of the seven trainers were black, as were 10 of the 13 jockeys.

-

Horses cross the finish line.

Raised in Nairobi by his grandparents, Fundi fell in love with horse racing when his grandfather started taking him to Ngong when he was 13. His grandfather persuaded Steve Njuguna, a former champion jockey and a trainer at the time, to teach Fundi how to race.

Fundi briefly worked as a groom before starting racing when he became eligible – at 16 – coming last in his first race and winning in his fifth. The 2024/25 season, his fifth, was his best.

The newly diverse scene, he said, has increased competition for jockeys and trainers.

Black trainers are making their mark too.

Joe Karari, 41, was one of those with horses racing on the Day of Champions.

-

Above: Joe Karari with a horse at his stables at Ngong Racecourse.

-

Left: The kit room at Karari’s stables. Far right: A groom washes a horse at Karari’s stables after training.

Born and raised near the racetrack in western Nairobi in what he describes as a household of horse lovers, he used to visit the venue with his family to cheer racehorses belonging to his uncles. After completing college, he spent a lot of time in stables, getting a job as a groom and work rider under trainer Oliver Gray.

He learned the ropes for five years and became a trainer in 2006, since when he has built his portfolio from six horses from one owner to 26 horses from 70 owners, including syndicates.

A perennial runner-up for the champion trainer title, Karari finally won it in the 2024/25 season with five meetings remaining, becoming the first black Kenyan to win it in a decade.

Karari is mentoring other black yard workers to become trainers. “This game is here to stay. And it belongs to everyone,” he said after a morning training session a few days before the last meet.

-

James Muhindi, a former champion jockey, checks the race card in the weighing room.

The owners of the horses that Karari trained in the 2024/25 season embody the evolving landscape of upper-class Kenyan society. They number among them foreigners, and whiteand black Kenyans. “It’s a mix of all sorts of people here,” he said.

K Bakor, a 54-year-old Kenyan businessman who joined the sport as a horse owner in 2022, is also helping diversify it by giving jockey opportunities to young, black stable workers. “We need to get a new generation,” said Bakor, who used to ride donkeys in races in the Kenyan coastal town of Lamu, where he was born.

Horse racing was introduced in Kenya in the 19th century, with venues opening up in different parts of the country as the sport grew in popularity. But now, Ngong Racecourse, which opened in 1954, is the only racetrack left.

During its heyday in the 1970s and 1980s in Kenya, the sport attracted thousands of spectators. However, its fortunes dwindled over time to a point a few years ago when, with near-empty stands, it was struggling to survive years of steady decline attributed to dwindling sponsorship and mismanagement.

Now the situation is improving with more local participation.

-

Crowds in the grandstand before a race.

The sport had always been dominated by white people, but in recent years, as increasing numbers have left the country, their places have been taken by black Kenyans who had access to horses, stables and training facilities through working in support roles such as groom work.

At the members’ lounge above the grandstand after the last race of the Day of Champions, Mutuota acknowledged the need for change and for the club “to have an open mind for racing to succeed”.

“We have to shed the traditional mentality that we’ve held on to,” said Mutuota, one of two black members of the club’s eight-person executive committee.

The jockey club is making attempts to revive horse racing through partnerships.

Kabir Dhanji, creative director at Kivuli Creative, an agency that the jockey club partnered with in 2023 to rebuild and grow the sport, said his company is treating horse racing as “a modern sport”. That has entailed marketing, advertising and social media content creation, as well as the introduction of pop-up restaurants and bars on the site, and between-race entertainment offers such as music and acrobatics.

-

Faces in the crowds at Ngong Racecourse.

Dhanji said the agency wants to make horse racing inclusive, family-friendly, accessible and “a sport for Kenyans by Kenyans”.

“The sport may have had a problematic past – not intentionally – and this was associated with colonialism, oppression, suppression, repression,” he said. “And Kenyans don’t want to be associated with that. They want to be able to come and express themselves.”

The efforts are paying off. At Ngong on the Day of Champions, the grandstand was packed with a multiracial mix of young and older spectators. On the turf next to it, spectators strolled about in sunglasses and colourful clothes. A little further away, parents watched their children bounce on inflatable castles. And elsewhere, punters sat glued to TV screens, monitoring their bets. By the last race, there were 5,000 people in attendance. Many stayed on for an afterparty that went late into the night.

“It’s become an event, and this is fantastic news,” said Michael Spencer, a British businessman who, alongside his wife, Sarah, is a benefactor of the jockey club and own a stud farm in central Kenya. “Now I’m not worried about the survival (of the sport). I just want to see it prosper, be more successful.”

-

Horses gallop down the final straight in a race.

The club will have to work harder, though, to maintain the momentum and retain talent. Professional jockeys earn £23 a ride. For the Day of Champions, there was about £4,000 up for grabs in total prize money for seven races. Some jockeys have in recent years relocated to Europe in search of the better pay they can get by exercising racehorses.

Sitting on a bench with his friends at the top section of the grandstand, David Mukuria, a 48-year-old construction worker who has been attending meets for about 15 years, was delighted that Fundi had emerged champion jockey.

“We feel happy when many black people are involved in the sport,” he said. “It shows that Africans have risen.”

3 months ago

56

3 months ago

56