“Manuscripts don’t burn,” the protagonist of Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita is told. This maxim is voiced by Satan, in reference to the Master’s destroyed opus. Having restored it, the devil punishes the man who tipped off the police about “illegal literature” kept in the Master’s flat, so as to move there himself. Bulgakov didn’t have to make this up. Surrounded by snitches, he managed to survive the Great Terror of the 1930s, as did his books. The Master and Margarita, on which he worked until his death in 1940, was first published uncensored in the USSR in 1973.

In the early 1990s, censorship was officially lifted in Russia. For a while, one could publish almost anything, but now literature has again become a target of oppression. Things have become particularly dire since 2022, the year Russia invaded Ukraine and criminalised “LGBT propaganda” among adults. In 2023 another bill was passed, outlawing the “international LGBT public movement” as extremist. These laws are now being deployed in Russia’s war on its book industry.

Earlier this year, Russian police, armed with a list containing 48 titles, raided several bookshops, ordering the staff to remove copies of the books on the list. Administrative proceedings were launched and fines issued. In May, 10 people affiliated with Eksmo, the country’s largest publishing corporation, were detained in Moscow. Three of them – Pavel Ivanov, Dmitry Protopopov and Artyom Vakhlyaev – were charged with “organising activities of an extremist organisation”, that is, distributing LGBTQ+-themed books. They remain under house arrest and face up to 12 years in prison.

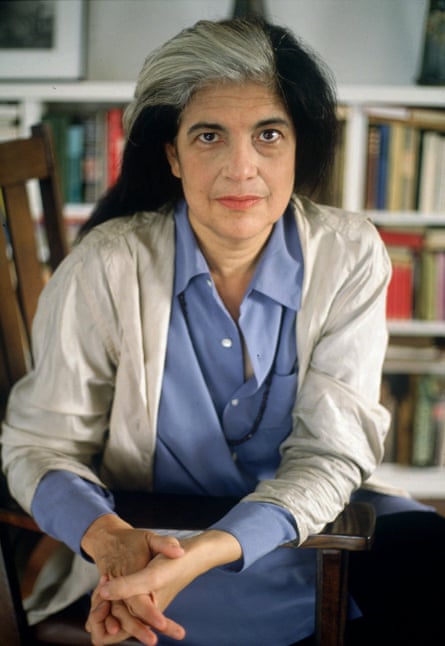

One of the books used as evidence in the case is Pioneer Summer, a bestselling novel by Elena Malisova and Katerina Sylvanova that was published in 2021 by Popcorn Books (a Moscow-based imprint now part-owned by Eksmo). Over the past three years, it has provoked outrage, particularly among Russian politicians, despite being anything but steamy: the teenage protagonists of this gay love story never go beyond kissing. At any rate, its runaway success was part of the driver for the Kremlin’s crackdown. Other titles that had to be withdrawn from sale include Russian editions of Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation and Olivia Laing’s Everybody, books that discuss homosexuality, though hardly in an extremist way.

It’s not just LGBTQ+-related topics, however loosely defined, that are deemed incendiary. Felix Sandalov, the director of StraightForward – an international project he cofounded to promote uncensored literature about Russia – told me about other taboos. They include comparisons between Stalinism and Nazism, unfavourable mentions of the Russian Orthodox church and, of course, any insufficiently patriotic takes on the current war in Ukraine.

Prohibitions keep multiplying. One piece of legislation will criminalise “propaganda” promoting childfree lifestyles. There are also plans to crack down on what Russian legislators call an “international Satanism movement”. If that happens, Bulgakov’s novel might disappear from the shelves again.

The result of Russia’s latest assault on free speech is a book industry in turmoil. Everyone is scared, several insiders told me, asking not to be named. The approach taken by the authorities – to keep people guessing what’s allowed and what’s not – appears to be an efficient intimidation strategy. Nevertheless, working under growing scrutiny, publishers have been devising countermeasures.

Sandalov, formerly the editorial director of Individuum (another Moscow-based imprint in which Eksmo recently bought a 51% stake), recalls how some of its authors were registered as “foreign agents” following the extension, in 2021, of another repressive law. “Initially we could still publish [these authors] provided we observed the labelling rules,” he says. While doing so, they found a witty way to partially circumvent the obligatory “produced by a foreign agent” warning by blurring it. Another clever move was their cover of Martha Gellhorn’s The Face of War, with its visual evocation of the letter Z, the symbol of Russia’s military aggression. The anti-war graffiti it inspired can be found in many cities.

With the prospect of criminal persecution looming large, however, fighting the censors is becoming too dangerous. Victoria, a publishing professional with links to the Russian book market, told me independent publishers are dropping any problematic subjects and instead branching out into new areas, such as Asian cultures and art history. She sees this as “a form of ideological opposition and survival in this totalitarian nightmare”.

Expecting the screws to be tightened further, some publishers compile their own lists of titles to be removed from shops. Such self-censorship is no doubt convenient to busy law enforcers. “In the 2010s,” Victoria says, “it was widely believed that … the authorities in this country don’t read books.” Whether they’ve since become avid and attentive readers is unclear. Their decision to ban Leslie Kern’s Feminist City – a study of urbanism – might be explained by their kneejerk tendency to ascribe LGBTQ+ connotations to the word “feminism”. As for Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet and Walter Benjamin’s One-Way Street, these works could only be blacklisted by someone who didn’t understand them at all.

But it’s not just the state wielding its own apparatus to further restrict freedom of expression. Ordinary readers also do their bit for law and order. Police are sometimes alerted to suspicious books by vigilantes who post offending passages on social media. The existence of informants is not surprising. I dislike a book, I complain about it, it gets banned; thus, my voice has been heard. In a country with no democratic mechanisms left, reporting something objectionable is the only way for an individual to participate in public life. Any community where people feel politically disengaged – as they increasingly do in the UK and across the world – risks descending into the same madness.

Censorship always relies on self-censorship, be it in Russia or in the west, where (to give but one example) venues cancel shows by artists protesting Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Speaking your mind is, naturally, fraught with more serious consequences in totalitarian states than in those where censorship is mostly limited to economic measures, but the gap is closing. Whatever your government’s human rights record, freedom of expression should never be taken for granted.

Unlike the fireproof manuscripts in Bulgakov’s fiction, real-life books, once banned, can be destroyed for ever. As the repressive campaign continues, pre-emptive self-censorship in Russia is gaining momentum. Last month Eksmo opened an exhibition at the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation – the federal agency that brought the case against the corporation’s employees – to celebrate “heroes past and present”, from Soviet secret policemen to those involved in the making of “the great legend”, as one of the books on display refers to the Ukraine war. Published with the support of the ministry of defence, it features Stalin’s name on page one. On page seven there is an error: the author got the month of Russia’s 2022 invasion wrong. The hagiographers of this war are as inept as those who wage it.

-

Anna Aslanyan is a journalist and translator, and the author of Dancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of History

3 months ago

39

3 months ago

39