It was last year when Valentyn Velykyi noticed Russia’s war with Ukraine was getting closer. In early summer, it arrived on his doorstep. “You could hear explosions day and night. Recently missiles started flying over my house. There’s a rumbling sound. You can see a trail in the sky,” the 72-year-old pensioner recalled.

Velykyi’s home is at No 18 Petrenko Street, in the small agricultural village of Maliyivka. It is located on the administrative border between Dnipropetrovsk and Donetsk provinces in central-eastern Ukraine. Once Russian troops were far away. Latterly, they have crept nearer, besieging the city of Pokrovsk and capturing one grassy meadow after another.

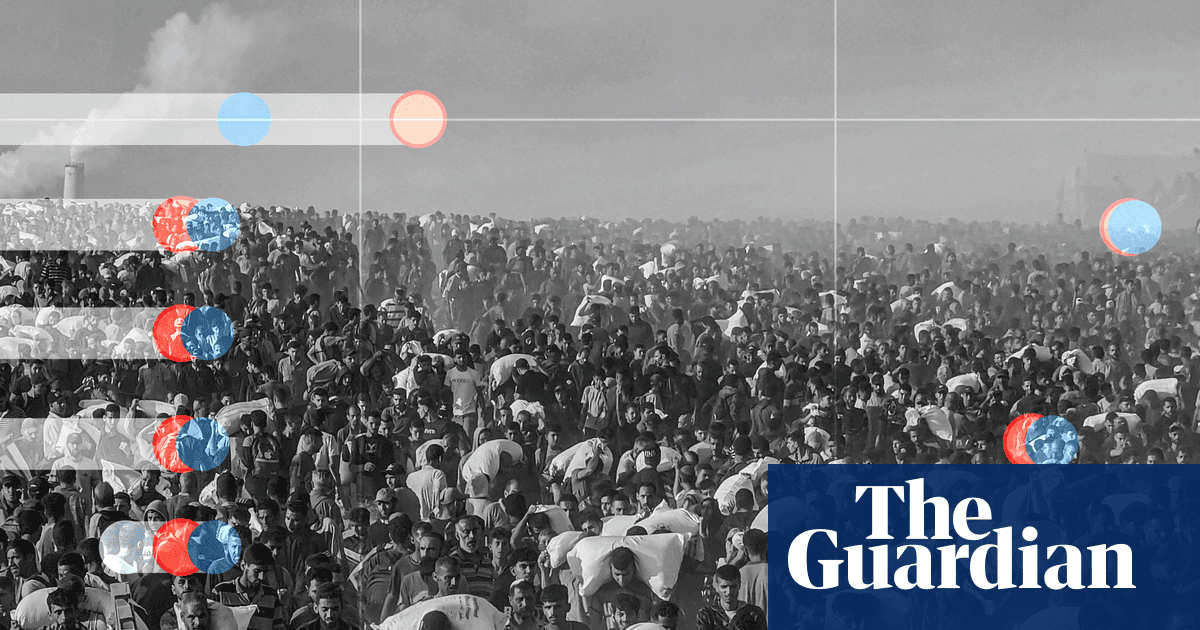

Europe’s biggest war since 1945 continues to rage. Its scale is epic: battles are fought across a 600-mile (965km) frontline. In recent months, the Kremlin has stepped up its bombardment of Ukraine’s cities and towns. Most nights it sends hundreds of drones and ballistic missiles. A weary population has got used to the wail of air raid sirens and the kettle drum boom of explosions.

In May, fighting engulfed Maliyivka. It became a Russian target. First, the house by the old bus stop was destroyed. Then everything got hit. The village’s 300-odd residents left, with the exception of Velykyi and his equally stubborn neighbour Mykola. For a while volunteers dropped off food and water for the pair. Eventually, when it got too dangerous, they stopped coming.

Last week, Velykyi went to call on his friend, bringing tea and sweets as usual, only to discover that Mykola had vanished. Dead chickens lay in the yard. “I called Mykola’s name but he’d gone. I thought: ‘My God, is it really true that our military is going to retreat,’” he said. He spent the next day hiding in a dugout made by Ukrainian soldiers, venturing out in the evening to fetch water from Mykola’s well.

While he was away a missile fell on his house. “I heard BANG. My shed was gone, in a split second. There was nothing left. It was probably a glide bomb or something,” he said. At dawn, he freed his animals and set off on foot across the fields. Behind, was his flattened home; to the right a crater-pitted road; ahead the large village of Velykomykhailivka. He walked for six hours under a sweltering sky.

For the first time, Russian combat units are close to seizing territory in Dnipropetrovsk oblast. In 2022, the Kremlin said it had “annexed” four Ukrainian provinces – Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia – despite only fully controlling Luhansk. Most believe Dnipropetrovsk will be added to this list, should Russian troops break through, in Maliyivka and elsewhere.

Since Donald Trump’s return in January to the White House, negotiations have taken place between Washington and Moscow over a possible peace deal. This week Volodymyr Zelenskyy restarted direct talks with the Kremlin. So far, though, Vladimir Putin, has refused to compromise. He wants Zelenskyy removed, Ukraine demilitarised and a new map of Europe drawn up, featuring a bigger Russia.

“That idiot Putin wants to take it all. Our most fertile land. That’s what it’s all about,” Velykyi said, climbing onboard a minibus owned by Proliska, a Ukrainian charity that rescues civilians. The vehicle trundled into Velykomykhailivka, led by soldiers riding in a green-painted van. On its roof were antennae and what looked like multisized upturned buckets: electronic equipment to disable Russian drones.

The village was eerily empty. A school with wooden totem poles and a mural painted with a dove was deserted. The owners of the bar and supermarket on the high street are gone, both shut for good. Apples lay on a verge, unpicked, alongside silent cottages and incongruously blooming kitchen gardens. A few buildings had been walloped. Most were intact. The enemy, it appeared, was coming.

“My country has a future. It’s just a question of time,” Serhii Andriyanov said, as volunteers stretchered his 85-year-old grandmother Halyna into an ambulance. “She had a heart attack six months ago,” he said. His mother, Svitlana, carried their meagre belongings: plastic bags; two kittens in a rectangular cardboard box; and a tub filled with eggs. The chickens would be staying behind.

The convoy picked up two more senior citizens. Police had used an armoured vehicle to collect one of them, Lidia Prysiazhena, from the underfire village of Havrylivka. How were things there? “Bad,” she replied. Another pensioner, Anatoliy Baraley, said he did not want to leave. “My daughter repeatedly badgered me to go somewhere safer.”

Ukrainian soldiers defending Dnipropetrovsk oblast describe the frontline as “stable” but acknowledge the situation is “dynamic”. “Our task is to stop them,” Capt Viktor Danyshchuk said. He conceded his mechanised brigade – the 31st – was short of drones, ammunition and infantry. “Our only option is to keep fighting. We are defending our land,” he said. Asked about Trump’s Ukraine policy, he said: “It’s hard to make sense of it.”

Alex Budilov, a combat officer with the brigade, said the Russians exaggerated their battlefield gains for propaganda purposes, in order to spread fear and panic among the local population. They had sustained colossal losses in manpower to achieve the “fleeting appearance of success”, he suggested. “A couple of dickhead Russian soldiers raise a flag next to a village. Minutes later we wipe them out,” he said.

Speaking in a rear forest camp, Budilov called Moscow’s assault tactics “insidious” and said it involved sacrificing hundreds of soldiers to achieve success. First, it sends in a heavily protected tank, nicknamed “the barn”, which is covered in bulky metal cages to repel Ukrainian drones. Other military vehicles accompany it. They include tanks, armoured personnel carriers and trucks loaded with assault troops.

A second motorised group follows made up of men on motorbikes and buggies. Their goal is to expose Ukrainian defensive positions. “They deliberately enter the kill zone and are neutralised after revealing our fire points,” Budilov said. Lastly, small groups of infantry are sent on one-way missions to infiltrate forest belts. “They clear minefields with their own bodies,” he said.

According to western estimates, Russia has suffered more than one million casualties, killed and wounded – a toll far higher than Soviet losses from the war in Afghanistan. “It’s a very Russian idea that you are a small part of something bigger. You sacrifice your life to do something for history. It’s a totalitarian mind virus,” Budilov suggested, arguing that Russians and Ukrainians were “very different”.

On top of kamikaze attacks, Russia has stepped up its bombardment of the Dnipropetrovsk region. At 9.40am on Saturday, a drone blew up outside a police station and outpatient clinic in the village of Oleksandrivka. Shrapnel killed a 70-year-old woman riding past on a moped, Valentyna Podolna. Another passerby Mykola Horoshko, died nearby, not far from a second world war memorial.

The scene afterwards was hellish. Podolna’s flip-flops lay on the pavement, next to a blood-spattered kerbstone and a white blanket, used to cover her body. The explosion incinerated parked cars, transforming them into ashen engine parts and smouldering metal. It shredded a grove of walnut trees; their stumps resembled giant black coral. Tiles on the roof of the shop opposite were left crazily askew.

“This happened because of imperial ambition,” Volodymyr Shevchenko, a driver at the medical clinic, said. He showed off the consultation rooms inside his ravaged workplace, now littered with broken glass. Parts of the bomb gouged holes in his ambulance. Shevchenko said: “Putin is a person suffering from schizophrenia. In public he behaves normally. In reality he is insane. His only desire is to force his goals on the world.”

Velykyi was dropped off at a registration centre in the city of Pavlohrad, which was also pounded last week by numerous drones and several missiles. Dozens of displaced people were already staying there. Most were elderly. Some dozed on metal-framed beds. They had been set up on the stage and around the auditorium of a former theatre.

Oleksandr Holovko, the head of Velykomykhailivka’s village council evacuation department, said people began leaving the area in February. On 1 June a compulsory evacuation order was issued to families with children. Holovko said he and the police chief had subsequently made various attempts to persuade Velykyi – the last person in his village – to depart, as fighting became intense.

“The place is completely destroyed. Every house is either fully in ruins or partially. It’s kapiets [messed up],” Holovko said, adding it was the same in neighbouring Sichneve and Novoselivka. Vitalii Hrychkoiedov, a field officer with Proliska, added: “Velykyi wouldn’t have survived had he stayed much longer. It’s very dangerous.”

Caseworkers asked the pensioner if he had a Ukrainian passport. He shook his head and said he arrived with nothing but his clothes: grubby trousers and a long-sleeved top. Before the war, his village was “excellent”. “I worked on a combine harvester. We had two roads, a shop and a school bus. Everyone was my friend,” he said. This spring, he had planted potatoes and onions in his vegetable patch.

“Everything is still there. It’s a shame,” he said.

-

Luke Harding’s Invasion: Russia’s Bloody War and Ukraine’s Fight for Survival, shortlisted for the Orwell prize, is published by Guardian Faber

3 months ago

45

3 months ago

45